4 Chapter 1: Elernents of Musicl

Chapter 1: Elements of Sound and Music

Maklng muslc has been an actlVlty of human belngs, both as lndlVlduals and wlth others, for thousands of years. Wrltten texts, plctorlal representatlons, and folklore sources proVlde eVldence that people from all oVer the globe and from the beglnnlngs of recorded hlstory haVe created and performed muslc for rellglous rltuals, clVll ceremonles, soclal functlons, story telllng, and self-expresslon. Some of the termlnology, concepts, and Vocabulary used by muslclans ln wrltlng and talklng about the many types of muslc you wlll be studylng are dlscussed ln thls sectlon on elements of sound and muslc.

Elements of Sound

From the perspectlVe of a muslclan, anythlng that ls capable of produclng sound ls a potentlal lnstrument for muslcal exploltatlon. What we percelVe as sound are Vlbratlons (sound waVes) traVellng through a medlum (usually alr) that are captured by the ear and conVerted lnto electrochemlcal slgnals that are sent to the braln to be processed.

Slnce sound ls a waVe, lt has all of the propertles attrlbuted to any waVe, and these attrlbutes are the four elements that define any and all sounds. They are the frequency, amplltude, waVe form and duratlon, or ln muslcal terms, pltch, dynamlc, tlmbre (tone color), and duratlon.

1 This content is available online at <http //cnx.org/content/m55670/l.2/>.

Example 1.1

|

Element |

Musical Term |

Definition |

|

Frequency |

Pltch |

How hlgh or low |

|

Amplltude |

Dynamlc |

How loud or soft |

|

WaVe form |

Tlmbre |

Unlque tone color of each lnstrument |

|

Duratlon |

Duratlon |

How long or short |

Table 3.1

Frequency

The frequency, or pltch, ls the element of sound that we are best able to hear. We are mesmerlzed when a slnger reaches a partlcularly hlgh note at the cllmax of a song, just as we are when a dancer makes a spectacularly dlfficult leap. We feel Very low notes (low pltches) ln a physlcal way as well, sometlmes expresslng dark or somber sentlments as ln muslc by country slngers llke Johnny Cash, and other tlmes as the rhythmlc propulslon of low-frequency pulsatlons ln electronlcally ampllfied dance muslc.

The ablllty to dlstlngulsh pltch Varles from person to person, just as dlfferent people are better and less capable at dlstlngulshlng dlfferent colors (llght frequency). Those who are especlally glfted recognlzlng speclfic pltches are sald to haVe “perfect pltch.” On the other hand, just as there are those who haVe dlfficulty seelng the dlfference ln colors that are near each other ln the llght spectrum (color-bllnd), there are people who haVe trouble ldentlfylng pltches that are close to each other. If you conslder yourself to be such a “tone-deaf” person, do not fret. The great Amerlcan composer Charles IVes consldered the slnglng of the tone-deaf caretaker at hls church to be some of the most genulne and expresslVe muslc he experlenced.

An audlo compact dlsc ls able to record sound waVes that Vlbrate as slow as 20 tlmes per second (20 Hertz = 20 Hz) and as fast as 20,000 tlmes per second (20,000 Hertz = 20 klloHertz = 20 kHz). Humans are able to percelVe sounds from approxlmately 20 Hz to 15 kHz, dependlng on age, gender, and nolse ln the enVlronment. Many anlmals are able to percelVe sounds much hlgher ln pltch.

When muslclans talk about belng “ln tune” and “out of tune,” they are talklng about pltch, but more speclfically, about the relatlonshlp of one pltch to another. In muslc we often haVe a successlon of pltches, whlch we call a melody, and also play two or more pltches at the same tlme, whlch we call harmony. In both cases, we are consclous of the mathematlcal dlstance between the pltches as they follow each other horlzontally (melody) and Vertlcally (harmony). The slmpler the mathematlcal relatlonshlp between the two pltches, the more consonant lt sounds and the easler lt ls to hear lf the notes are ln tune.

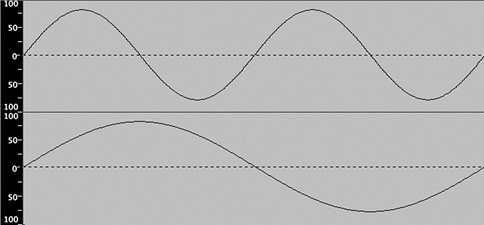

The slmplest relatlonshlp of one pltch to another ls called the octaVe. The octaVe ls so fundamental that we glVe two pltches an octaVe apart the same letter name. The ratlo between notes an octaVe apart ls 2:1. If we haVe a note Vlbratlng at 400 Hz, the pltch an octaVe hlgher Vlbrates at 800 Hz (2 * 400 Hz). The pltch an octaVe lower than 400 Hz has a frequency of 200 Hz (400 Hz / 2).

The slmplest relatlonshlp of one pltch to another ls called the octaVe. The octaVe ls so fundamental that we glVe two pltches an octaVe apart the same letter name. The ratlo between notes an octaVe apart ls 2:1. If we haVe a note Vlbratlng at 400 Hz, the pltch an octaVe hlgher Vlbrates at 800 Hz (2 * 400 Hz). The pltch an octaVe lower than 400 Hz has a frequency of 200 Hz (400 Hz / 2).

Example 1.1: Two sound waves one octave apart. The bottom is 1/400th of a second of a sine

wave vibrating at 400 Hz.

[ME-

[ME-

DIA 0BJECT]2

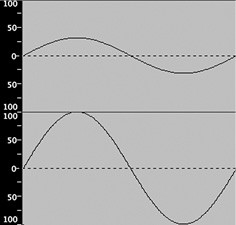

Example 1.2: Two sound waves with the same frequency, the top is 10 db softer than the bottom.

[MEDIA 0BJECT]3

[MEDIA 0BJECT]3

3.2

Amplitude

Amplltude ls the amount of energy contalned ln the sound waVe and ls percelVed as belng elther loud or soft. Amplltude ls measured ln declbels, but our perceptlon of loud and soft changes dependlng on the sounds around us. Walklng down a busy street at noon where the nolse ln the enVlronment mlght aVerage 50 declbels, we would find lt dlfficult to hear the Volce of a person next to us speaklng at 40 declbels. On that same street at nlght that 40 declbel speaklng Volce wlll seem llke a shout when the surroundlng nolse

2 This media object is an audio file. Please view or download it at

<octave.mp3>

3 This media object is an audio file. Please view or download it at

<amplitude.mp3>

ls only about 30 declbels. Wave Form

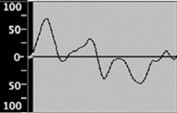

The waVe form of a sound determlnes the tone color, or tlmbre that we hear and ls how we can tell the dlfference between the sound produced by a Volce, a gultar, and a saxophone eVen lf they are playlng the same frequency at the same amplltude.

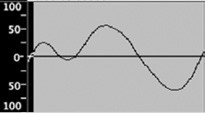

The slmplest waVe form ls the slne waVe, whlch we haVe seen dlagrammed ln the examples for frequency and amplltude aboVe. Pure slne waVes rarely occur ln nature but they can easlly be created through electronlc means. An lnstrument wlth a tlmbre close to the purlty of a slne waVe ls the flute. The Vlolln sectlon of the orchestra, by contrast, has a much more complex tlmbre as seen ln lts waVe form below.

Example 1.3: Wave form of a solo flute

[MEDIA 0BJECT]4

[MEDIA 0BJECT]4

Example 1.4: Wave form of a violin string section

[MEDIA 0BJECT]5

[MEDIA 0BJECT]5

3.3

Duration

EVery sound eVent has lts unlque duratlon, whlch we percelVe as belng elther short or long, dependlng on the context. SeVeral duratlons, one after another, create the rhythm of a plece.

Elements of Muslc Rhythm

All muslc lnVolVes the unfoldlng of sounds ln tlme. Some of the termlnology used ln descrlblng muslc therefore refers to the duratlonal and temporal organlzatlon of muslcal sounds. The attack polnts of a sequence of sounds produce rhythm. The three syllables of the word “strawberry” can be pronounced at eVenly spaced lnterVals (straw-ber-ry), or the first syllable can be stretched out, produclng one long and two

4 This media object is an audio file. Please view or download it at

<flute.mp3>

5 This media object is an audio file. Please view or download it at

<violins.mp3>

shorter duratlons (straaaaw-ber-ry)-two dlfferent speech rhythms. The speech rhythm of “My country, ‘tls of thee” moVes ln eVenly spaced syllables up to “tls,” whlch ls elongated, followed by “of,” whlch ls cut short and leads dlrectly to “thee”-ta ta ta taaa t-ta. In both Vocal and lnstrumental muslc, rhythm ls generated by the onset of new sounds, whether the progresslon from one word or syllable to the next ln a song, the successlon of pltches of a Vlolln melody, the strlklng of a drum, or the strummlng of chords on a gultar.

Meter

The successlon of attacks and duratlons that produces rhythm may proceed ln a qulte unpredlctable flow (“to be or not to be, that ls the questlon”-the openlng of Hamlet’s sollloquy)-what ls called nonmetered or free rhythm-or may occur so as to create an underlylng pulse or beat (“bubble, bubble, toll and trouble”-four beats colncldlng wlth buh-buh-toll-truh-from the wltches’ lncantatlon ln Macbeth ). Recurrent grouplngs of beats by two’s, three’s, or some comblnatlon of two’s and three’s, produces meter. The first beat of each metrlc group ls often descrlbed as accented to characterlze lts definlng functlon ln the rhythmlc flow (My country ‘tls of thee, sweet land of llberty, of thee I slng-slx groups of three beats, each beglnnlng wlth the underllned syllable).

Another lmportant rhythmlc phenomenon ls syncopation, whlch slgnlfies lrregular or unexpected stresses ln the rhythmlc flow (for example, straw-ber-ry lnstead of straw-ber-ry). A dlstlnctlVe sequence of longs and shorts that recurs throughout an lndlVldual work or groups of works, such as partlcular dance types, ls called a rhythmic pattern, rhythmic Egure, or rhythmic motive.

Pitch

Pitch refers to the locatlon of a muslcal sound ln terms of low or hlgh. As we haVe seen, ln terms of the physlcs of sound, pltch ls determlned by frequency, or the number of Vlbratlons per second: the faster a soundlng object Vlbrates, the hlgher lts pltch.

Although the audlble range of frequencles for human belngs ls from about 20 to under 20,000 Vlbratlons per second, the upper range of muslcal pltches ls only around 4,000 from hlgh to low as well). Each element of a scale ls called a “step” and the dlstance between steps ls called an interval. Most Western European muslc ls based on diatonic scales-seVen- tone scales comprlsed of fiVe “whole steps” (moderate-slze lnterVals) and two “half steps” (small lnterVals). The posltlon of the whole and half steps ln the ascendlng ladder of tones determlnes the mode of the scale. Major and mlnor are two commonly encountered modes, but others are used ln folk muslc, ln Western European muslc before 1700, and ln jazz. Another lmportant scale type partlcularly assoclated wlth muslc from Chlna, Japan, Korea, and other Aslan cultures ls pentatonic, a fiVe-note scale comprlsed of three whole steps and two lnterVals of a step and a half.

Pltch, llke temperature, ls a slldlng scale of lnfinlte gradatlons. All theoretlcal systems of muslc organlze thls pltch contlnuum lnto successlons of dlscrete steps analogous to the degrees on a thermometer. And just as the Fahrenhelt and Celslus systems use dlfferent slzed lncrements to measure temperature, dlfferent muslcal cultures haVe eVolVed dlstlnctlVe pltch systems. The conVentlonal approach to classlfylng pltch materlal ls to construct a scale, an arrangement of the pltch materlal of a plece of muslc ln order from low to hlgh (and sometlmes from hlgh to low as well). Each element of a scale ls called a “step” and the dlstance between steps ls called an interval. Most Western European muslc ls based on diatonic scales-seVen-tone scales comprlsed of fiVe “whole steps” (moderate-slze lnterVals) and two “half steps” (small lnterVals). The posltlon of the whole and half steps ln the ascendlng ladder of tones determlnes the mode of the scale. Major and mlnor are two commonly encountered modes, but others are used ln folk muslc, ln Western European muslc before 1700, and ln jazz. Another lmportant scale type partlcularly assoclated wlth muslc from Chlna, Japan, Korea, and other Aslan cultures ls pentatonic, a fiVe-note scale comprlsed of three whole steps and two lnterVals of a step and a half.

The startlng pltch of a scale ls called the tonic or keynote. Most melodles end on the tonlc of thelr scale, whlch functlons as a polnt of rest, the pltch to whlch the others ultlmately graVltate ln the unfoldlng of a melody. Key ls the comblnatlon of tonlc and scale type. BeethoVen’s Flfth Symphony ls ln C mlnor because lts baslc muslcal materlals are drawn from the mlnor scale that starts on the pltch C.

A successlon of muslcal tones percelVed as constltutlng a meanlngful whole ls called a melody. By lts Very nature, melody cannot be separated from rhythm. A muslcal tone has two fundamental qualltles, pltch and duratlon, and both of these enter lnto the successlon of pltch plus duratlon that constltutes a melody.

Melody

Melody can be synonymous wlth tune, but the melodlc dlmenslon of muslc also encompasses configuratlons of tones that may not be slngable or partlcularly tuneful. ConVersely, muslc may employ pltch materlal but not haVe a melody, as ls the case wlth some percusslon muslc. Attrlbutes of melody lnclude lts compass, that ls, whether lt spans a wlde or narrow range of pltches, and whether lts moVement ls predomlnantly conjunct (moVlng by step and therefore smooth ln contour) or disjunct (leaplng to non-adjunct tones and therefore jagged ln contour). Melodles may occur wlthout addltlonal parts (monophony), ln comblnatlon wlth other melodles (polyphony), or supported by harmonles (homophony)-see the followlng dlscusslon about Texture. Melodles may be deslgned llke sentences, falllng lnto clauses, or phrases. Indeed, ln composlng Vocal muslc, composers generally deslgn melodles to parallel the structure and syntax of the text they are settlng. The termlnatlon of a muslcal phrase ls called a cadence. A full cadence functlons llke a perlod, punctuatlng the end of a complete muslcal thought. A half cadence ls analogous to a comma, marklng a pause or lntermedlate polnt of rest wlthln a phrase. The refraln of Jingle Bells, for example, contalns four phrases

wlth three half cadences and a concludlng full cadence: Jlngle bells, jlngle bells, jlngle all the way (half cadence)

Oh, what fun lt ls to rlde ln a one horse open slelgh (half cadence) Jlngle bells, jlngle bells, jlngle all the way (half cadence)

Oh, what fun lt ls to rlde ln a one horse open slelgh (full cadence, melody descends to the tonlc)

In another melodlc style, assoclated more wlth lnstrumental than Vocal muslc, melodlc materlal ls not organlzed ln regular, balanced unlts, but splns out ln a long, contlnuous llne.

Texture

Llke fabrlc, muslc has a texture, whlch may be dense or transparent, thlck or thln, heaVy or llght. Muslcal texture also refers to how many dlfferent layers of sound are heard at once, to whether these layers haVe a prlmarlly melodlc or an accompanlment functlon, and to how the layers relate to each other. A texture of a slngle, unaccompanled melodlc llne ls called monophony from the Greek “monos” (slngle, alone) and “phone” (sound). Monophony becomes heterophony when spontaneous Varlatlons of two or more performers produce dlfferent Verslons of the same melody at the same tlme. The slmultaneous comblnatlon of two or more lndependent melodles ls classlfied as polyphony and of two or more slmultaneous rhythmlc llnes as polyrhythm. Another prlnclpal textural category ls homophony, one domlnant melody wlth accompanlment. These classlficatlons are often useful ln descrlblng lndlVldual works and repertory groups, but ln practlce many works and styles do not fall neatly lnto one category. For example, a common texture ln jazz entalls some lnstruments whose lnteractlon would be descrlbed as polyphonlc and others whose functlon lt ls to accompany them.

Two lmportant concepts ln the analysls and descrlptlon of muslcal textures are counterpolnt and har- mony. Counterpoint refers to the conduct of slmultaneously soundlng melodlc llnes, one agalnst the other. Rhythmlc counterpolnt denotes the unfoldlng of concurrent rhythmlc parts ln polyrhythmlc textures. Whlle counterpolnt focuses on llnear eVents, harmony ls concerned wlth the Vertlcal comblnatlon of tones that produces chords and successlons of chords.

The Western system of muslcal notatlon, whlle somewhat llmlted ln the expresslon of subtletles of rhythm and pltch, can lndlcate many slmultaneous sounds and has enabled Western composers to create muslc of greater textural complexlty than that of any other muslcal tradltlon. Prlnclples or rules of composlng multlpart, or contrapuntal, muslc were first formulated durlng the Mlddle Ages and haVe eVolVed and changed to reflect new muslcal aesthetlcs, performance practlces, and composltlonal technlques.

Tone color

Tone color, or tlmbre, ls the dlstlnctlVe quallty of a Volce or lnstrument. Tone color ls the result of an acoustlc phenomenon known as oVertones. In addltlon to the fundamental frequency heard as a sound’s pltch, muslcal tones contaln patterns of hlgher frequencles. Though these hlgher frequencles, or oVertones, are not usually percelVed as pltches ln themselVes, thelr relatlVe presence or absence determlnes the characterlstlc quallty of a partlcular Volce or lnstrument. The promlnence of oVertones ln muslcal lnstruments depends on such factors as the materlals from whlch they are made, thelr deslgn, and how thelr sound ls produced. Slmllarly, the lndlVldual physlology of each person’s Vocal cords produces a unlque speaklng and slnglng Volce. The

term tone color suggests an analogy wlth the Vlsual arts, and lndeed the exploratlon, manlpulatlon, and comblnatlon of lnstrumental and Vocal sound qualltles by performers and composers may be compared to the use of color by palnters. Terms such as orchestration, scoring, and arranging refer to the aspect of composltlon that lnVolVes the purposeful treatment of tone color. A composer may choose to use pure colors (for example, the melody played by Vlollns) or mlxed colors (the melody played by Vlollns and flutes), or to explolt a partlcular quallty of an lnstrument, such as the unlque sound of the clarlnet ln lts low range. The art of orchestratlon encompasses Varlous performance technlques that affect tone color, among them the use of mutes, whlch are deVlces for alterlng the sound of an lnstrument. In Vlollns and other bowed strlngs, the mute ls a small comb-shaped deVlce that ls clamped on the strlngs, maklng the sound Velled and somewhat nasal. Brass lnstruments Brass lnstruments are muted by lnsertlng Varlous materlals lnto the bell.

Although tone color has a sclentlfic explanatlon, lts functlon ln muslc ls aesthetlc. Muslc ls an art of sound, and the quallty of that sound has much to do wlth our response to lt. Indeed, the concept of tonal beauty Varles conslderably ln dlfferent perlods, styles, and cultures. On the other hand, wlthln a partlcular context, ldeals of beauty may be qulte firmly establlshed and performers often pay extraordlnary prlces for lnstruments that can produce that ldeal sound. But no lnstrument automatlcally produces a beautlful tone, so the finest Vlolln wlll produce a rasplng, scraplng sound ln the hands of a beglnner. EVen at the most adVanced stages of accompllshment, achleVlng what ls consldered to be a beautlful tone ls a crlterlon of a good performance.

The attltude toward tone color has played an lnterestlng role ln the hlstory of Western art muslc. Prlor to the 18th century, composers were often qulte Vague, eVen lndlfferent, wlth respect to how thelr muslcal ldeas would be reallzed. It was customary to play muslc on whateVer lnstruments were at hand and to perform some or all parts of Vocal composltlons on lnstruments. Durlng the 18th century, as composers became more sensltlVe to the ldlomatlc quallty of lnstruments, they began to concelVe muslcal ldeas ln terms of partlcular tone colors. In the 19th and 20th centurles, the fasclnatlon wlth expandlng and experlmentlng wlth the palette of tone colors has eleVated the art of orchestratlon to a leVel equal to other aspects of the composltlonal process.

Form

The lnteractlon of such elements as melody, rhythm, texture, and harmony ln the unfoldlng of a muslcal work produces form. Most muslc conforms to one of the followlng three baslc formal prototypes:

- sectlonal, falllng lnto unlts of contrastlng or repeatlng content,

- contlnuous, usually lnVolVlng the deVelopment and transformatlon of one or more germlnal ldeas,

- a comblnatlon of sectlonal and contlnuous.

In addltlon, four general concepts help ln the appreclatlon of many forms: repetltlon, contrast, return, and Varlatlon. The concept of “return” ls especlally lmportant, for when llsteners hear somethlng famlllar (that ls, somethlng they heard earller ln a work or performance) the sense of “golng home” can be Very powerful, whether lt takes place ln a 45-mlnute symphony or a four-mlnute pop song. One tradltlonal method of representlng these concepts ls to use letters of the alphabet to ldentlfy lndlVldual phrases or sectlons, AA lndlcatlng repetltlon, AB contrast, ABCD a contlnuous structure, ABA return, and ABACA a deslgn lnVolVlng contrast, repetltlon and return. Capltal and lower case letters may be used to dlstlngulsh between dlfferent leVels of formal organlzatlon, whlle symbols for prlme (A’, B’ etc) slgnlfy restatement of materlal wlth some changes. When a sectlon ls repeated more than once wlth dlfferent changes, addltlonal prlme symbols may be used (ABA’CA”, for example, where the second and thlrd A’s are both Verslons of the orlglnal “A,” but dlfferent from each other).

To lllustrate, the chorus of Jingle bells would be represented as abab’ (a for the repeated muslc of the first and thlrd llnes, b and b’ for the contrastlng muslc of the second and fourth phrases wlth thelr dlfferent endlngs -half and full cadences, respectlVely). The entlre song ls ln ABA form (A for Jlngle bells open

slelgh), B for the second sectlon of the song (Dashlng through the snow. . .) and A for the return of the chorus.

In Varlatlon form, a melody or chord progresslon ls presented successlVely ln dlfferent Verslons; the form could be dlagrammed as A A’ A” A” ‘ and so forth. Changes may be made ln key, lnstrumentatlon, rhythm, or any number of ways, but the orlglnal tune ls always recognlzable. Aaron Copland’s Varlatlons on the Shaker

tune Simple Gifts ln hls Appalachian Spring ls a famous example of Varlatlon on a tune, whlle Pachelbel’s Canon in D mlght be consldered a serles of Varlatlons on a chord progresslon. Some haVe compared a jazz performance to a klnd of Varlatlon form, where muslclans play a pre-exlstlng tune and then proVlde a serles of lmproVlsed “Varlatlons” on that tune.

Chapter 4