8 Chapter 8

Music of the World

By Cathy Silverman

“The curious beauty of African music is that it uplifts even as it tells a sad tale. You may be poor, you may have only a ramshackle house, you may have lost your job, but that song gives you hope.”

— Nelson Mandela

Fig. 8.1: Smkphotos, Dr. Cheng Yu playing the P’ipa, 2008.

Many indigenous cultures believe in the power of music to interact with cosmic energy. This knowledge has traditionally been used throughout history by indigenous peoples to maintain harmony with the universe, both in the past and continuing today. Around the world, the sound is often seen as having the ability to interact with unseen energy forces. Although music therapy is a new concept in the West, music has been used for thousands of years by animistic societies.

Animistic cultures utilize traditional healers, known as shamans to interact with the physical and spiritual realms. These societies use music, art, theater, and dance to bring balance to the community and its environment.

Often, the main purpose of music in traditional indigenous cultures is to maintain harmony. Sacred sounds are used to invoke energy forces. Some types of sacred music and rhythms affect brain waves in the range of four to eight hertz, which are called theta waves.

This is a type of brainwave connected to creativity, dreaming, and memory. Theta waves are produced during meditation, prayer, and spiritual awareness, which can induce a trance state (“The Science of Brainwaves”).

From a traditional perspective, through the use of rituals, cosmic energy is released that keeps the universe and humans in harmony. Around the world, sacred sounds are used for many purposes—spirituality, healing, controlling the weather, bringing good fortune, and others. Numerous cultures studied sound as a science and developed music to a high level of advancement. The sound was used as an intermediary between the material and non-material realms.

Most evidence of the use of music in primitive/archaic cultures demonstrates that music was primarily used in sacred rituals created for various purposes, such as attracting the attention of the spirits of nature, healing the sick, bringing good fortune, and repelling negative forces. Essentially, the shaman is humanity’s original multimedia artist, utilizing music, dance, visual art, and theater to interact with the forces of the universe with the intention of bringing balance and harmony to both the community and the environment.

Shamans around the world do not perceive music as something merely for entertainment; instead, music is seen as having the ability to interact with seen and unseen reality.

Numerous cultures studied the interaction of sound with the physical and spiritual worlds as a science and developed that science’s potential to amazingly advanced levels of understanding and expression. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, physicists and other scientists are arriving at the conclusion that all matter is composed of energy or vibration. The power of music is not solely abstract but is also physical. The air vibrations of sound are not only real and measurable, but they are also capable of affecting the physical world. An excellent example of this effect is the ability of an opera singer to cause the glass to shatter by singing a high note. Music and other forms of sound can cause various sympathetic vibratory resonances within objects at a distance (sympathetic vibration is a phenomenon in which a vibration produced in one object produces the same vibration in another object). Contemporary research into sounds with frequencies below the threshold for human hearing suggests that nausea or headache may be caused by sounds emitted by machinery at a distance. Rhythm also can be a powerful force. For centuries, military experience has held that when troops marching in unison need to cross a bridge, the commanding officer should give the order to break the step. The effect of marching in step has more than once led to the collapse of bridges, such as the Angers Bridge collapse.

The power of intention when combined with music is another concept understood well by the ancients that is beginning to be recognized by modern science. The power of intention refers to the understanding that sound has the ability to transmit the intention of the one creating the sound to the one receiving it. Intention, this belief claims, is part of the energy behind sound. This concept has been tested by kinesiology demonstrations theorizing that an angry or negative thought coupled with sound causes the body to weaken; conversely, a positive intention results in strengthening. The belief in the power of intention is one reason why music is often used in healing rituals around the world.

Traditional peoples express their deep respect and connection to their environment through the use of music and intention within a ritualized context. These rituals reflect an extraordinary understanding of the nature of vibration, the local ecology, and their effects on the human mind and body. These concepts can be embodied in the Hindu Sanskrit saying, “Nada Brahma,” which means “The world is sound.” This idea is embraced by almost every indigenous culture in the world, which will be further explored in this chapter.

Listening Objectives

Your listening objectives during this chapter will be to:

- Identify different traits found in the different world music styles.

- Listen for instrumentation and timbres, including voices or instruments that are performing.

- Observe small motifs in music and listen for their repetition, manipulation, change, and overall presentation throughout a piece; this includes the return of familiar musical sounds and/or melodies that could signal a repeated section in the larger form of the work.

- Listen for dynamic and tempo changes, including sudden loud or soft passages and sudden faster or slower sections.

- Practice describing these observed concepts using the music terms instrumentation, timbre, texture, tempo, dynamics, and form.

Key Music Terms

This chapter will not use the “tool” icon as has been used in other chapters, except to highlight a few instrumentation descriptions. By now, readers should have developed some confidence in identifying and describing timbre or tone quality, texture, tempo, dynamics, and form. These terms are included as needed in each world music discussion that follows.

Australia

Australian Aborigines represent one of the oldest continuous cultures living on earth today, tracing their history back more than fifty thousand years (“Aboriginal People”). Upon the arrival of Europeans in the eighteenth century, there were approximately one million Aborigines living in Australia. These Aborigines represented five hundred distinct tribes speaking more than two hundred languages (Chatwin 21). In general, the Europeans did not treat the indigenous peoples of Australia with respect or kindness. By the mid-twentieth century, the Australian Aboriginal population was reduced to sixty thousand members (“Aboriginal People”). These remaining people were forced to speak English and were moved to government camps. Children were taken away from their families in order to be raised in white homes. Although Australian Aborigines were forced to assimilate into Western culture, they were not granted citizenship until 1967 (Cameron). Land rights were not extended until the Aboriginal Land Rights Act of 1976 (“The Aboriginal Land Rights Act”). Today, most Australian Aborigines have been acculturated into modern Australian society. However, they face many of the same problems experienced by other colonized indigenous peoples, including high rates of unemployment and substance abuse, and continued discrimination within their respective societies (“Aboriginal Issues”).

Traditionally, Australian Aborigines are hunter-gathers and represent one of the few cultures on earth that did not undergo the Neolithic Revolution—meaning the indigenous peoples of Australia did not engage in agriculture or settle into permanent villages. They also did not domesticate large animals or accumulate many material objects. The central focus of traditional Australian Aboriginal culture is to reaffirm the energy of the land, thereby guaranteeing its continued existence. Aboriginal religion is an expression of cultural knowledge preserved in memory and enacted through music and dance.

Fig. 8.2: Bill Brindle, During the rain dance in Corroboree, 2005. This photo depicts a traditional Aboriginal corroboree, a ceremony with songs and symbolic dances.

The Dreamtime and Songlines

The foundational principles of Australian religion, music, and culture are based upon the Dreamtime. During this period, Ancestral Beings “dreamed” the land and heavens into existence, using music and dance to “sing” the world into creation. The Dreamtime knows no time; it is eternal. Therefore, Aboriginal existence is part of eternal existence. The Dreamtime is not a dream in the Western sense; rather, it is an ongoing process with the earth regarded as a conscious creation that nurtures seen and unseen reality. Australian Aboriginal music, dance, and ritual are expressions of these concepts, which are based upon songs received from the Dreamtime.

Legends are sung and danced daily; each series of stories creates a path (or “songline”) that connects locations of mythic episodes. Songlines are maps of specific locations and experiences, serving as a network of communication and cultural exchange that guides all of the nomadic movements of Australian Aborigines; they can find their way simply by knowing the song of a geographic area. These songlines cover the Australian continent. Specific tribes “own” a section of the songlines, and have the responsibility of maintaining it. Through these songlines, the entire continent of Australia can be seen as a sort of musical score (Chatwin 43).

Songlines are not only ritualistic; they also serve an important practical purpose— survival. Australia has a multiplicity of microclimates. A person from one area would have detailed knowledge of its flora and fauna, land formations, streams, and other geographic features. By naming all of the details of a particular area through a song, a person could survive (interestingly, birds also sing their territorial boundaries). It is fascinating to note that songlines also correspond to subtle lines of magnetic energy that flow around the earth.

Aborigines, along with many other native peoples, see these magnetic lines as the blood of

the gods. Initiated men and women learned to travel these lines using their “spirit” bodies, and claimed to gain the ability to communicate between people separated by vast distances (Chatwin 47).

Traditionally, songlines, rather than things, were the principal focus of trade within Australian Aboriginal culture. Songs were inherited, serving as deeds to the territory. These songs could be lent and borrowed, but they could never be sold. Songs were traded through “walkabouts,” which always traveled a specific songline inherited through totemic association (a totem is an animal, plant, or natural object that serves as the symbol of a specific clan or kinship group). Walkabouts are ritual journeys tracing the footprints of the Ancestors. From an Aboriginal perspective, the land must continue to be sung because land that is no longer sung will die—considered a great crime within Aboriginal culture. In addition, singing a song incorrectly or in an improper order is believed to have the ability to cause reality to cease to exist. The singing of songs on a walkabout is conceptually and literally recreating creation, linking past and present, and connecting singers to an ancient continuum (Chatwin 51).

Songlines do not convey information through words, but rather through melody, rhythm, or both. Songs are associated with totemic lines. A song will follow a particular melodic structure, even when the songline is thousands of miles long. Therefore, even if a person does not know the language, a songline and its totemic line can be recognized based on the melodic pattern of a particular song. This recognition has deep significance due to the strong connection of Aborigines to their totemic line (Chatwin 52).

Australian Aboriginal Instruments

For the Australian Aborigine, observation of nature immediately requires a state of empathy, which leads to imitative expression. Traditionally, Aboriginal music is influenced by animal sounds—the flapping of wings, the thump of feet on the ground—and other sounds in nature—wind, thunder, trees creaking, water running, and more. These sounds are reflected in the instruments used in Aboriginal music, such as the didgeridoo, which can produce sounds that imitate those found in the natural environment.

For the Australian Aborigine, observation of nature immediately requires a state of empathy, which leads to imitative expression. Traditionally, Aboriginal music is influenced by animal sounds—the flapping of wings, the thump of feet on the ground—and other sounds in nature—wind, thunder, trees creaking, water running, and more. These sounds are reflected in the instruments used in Aboriginal music, such as the didgeridoo, which can produce sounds that imitate those found in the natural environment.

Traditional Aboriginal music consists mainly of singing supported by a few instruments. Traditional Aboriginal instruments are usually percussive and are commonly mixed with sounds created by using the body, such as hand claps, body slapping, or the hitting of boomerangs or clapsticks (two sticks struck together). The didgeridoo (or yidaki) is probably the most recognizable of the Australian Aboriginal instruments. It is a wind instrument made from a log hollowed by termites. It produces a constant drone that includes a wide variety of rhythmic patterns and accents. It can produce many different tone colors, which are created by the performer through altering the shape of the mouth and the position of the tongue. An advanced didgeridoo player uses a circular breathing technique that does not require pausing to take a breath. Didgeridoos also can produce two different notes simultaneously that are alternated to produce complex rhythms. Watch this video for an example of the Aboriginal didgeridoo.

Fig. 8.3: Thomasgl. Image of didgeridoo, 2003.

Another interesting instrument used in Australian Aboriginal music is the bullroarer, which is a piece of wood attached to a long string that is swung to produce a roaring sound. Bullroarers are often used before a sacred ceremony to produce a sound that serves to warn the uninitiated to not approach the ceremony and as a method of cleansing the area (“Aboriginal Artefacts”).

Fig. 8.4: William Alfred Howitt, The Narrang-ga bull-roarer, 1904.

For more information about Australian Aboriginal music and culture, visit the Aboriginal

Australia Art & Culture Centre.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Music and dance are the lifeblood of African culture. There are dozens of tribes in sub-Saharan Africa, each with unique forms of music, dance, and ritual. The following are a few styles found in western and central Africa.

Fig. 8.5: TUBS, Ghana in Africa, 2011. In this map of Africa, the country of Ghana is highlighted in red.

Music of the Dagomba, Ghana

The Dagomba live in northeastern Ghana and speak a language called Dagbani. The main performers of Dagomba music are lunsi, who are from a hereditary clan of drummers. Lundi are responsible for many aspects of Dagomban life, serving as historians, cultural experts, genealogists, and counselors to royalty. Lundi performs at many Dagomban festivals and ceremonies.

The primary instrument in Dagomban music is the luna, a cylindrical, carved drum with a snare on each of its two heads. By squeezing the leather cords strung between its two heads, a player can change the tension and thus the pitch of the drum tone. In the

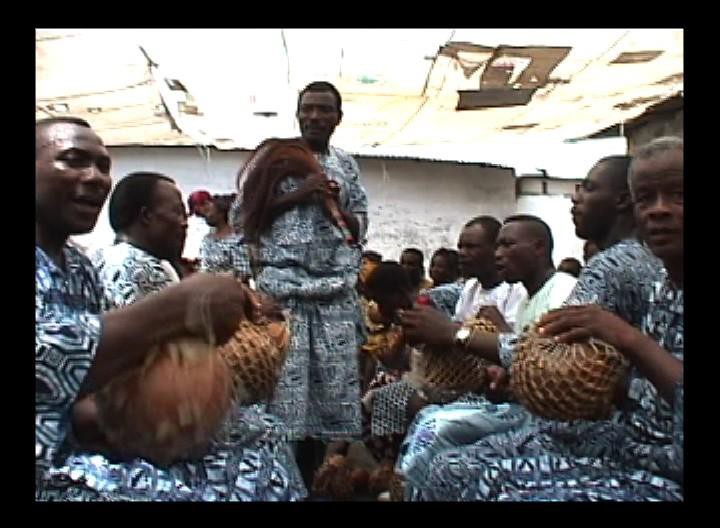

Fig. 8.6: Cathy Silverman, Dagomban musicians leading First Lady of Surinam into Voices of African Mothers Conference, 2010.

hands of an expert, the luna’s sound closely resemble the Dagomban language. Many types of Ghanaian music relate to speech. In Dagomban music, the connection between music and language is direct, and it is possible for an instrument to play the music that conveys verbal language. The luna, also known as the talking drum, is the main feature of this music. Talking drums are used to send messages and relate stories because they imitate the sound of speech (Silverman and Spezzacatena). Watch a demonstration of the talking drum.

Fig. 8.7: Cathy Silverman, Luna, 2010. Fig. 8.8: Cathy Silverman, Gungon, 2010.

The other main instruments in Dagomba music include the gungon, a medium-sized, barrel-shaped drum with a single head that is played with a curved stick and carried by a strap around the neck. Another common instrument is the gonje, a one-string bowed lute (a string instrument with a neck and a pear-shaped body) mounted on a calabash gourd covered with crocodile or alligator skin. The gonje is traditionally used to extol the majesty, valor, and good deeds of the chief or king (Silverman and Spezzacatena).

Fig. 8.9: Cathy Silverman, Gonje, 2010. The photo depicts a traditional Dagomban musician playing the gonje.

Listen to “ChiefInstallation,” an example of traditional Dagomban music.

Damba

Festivals in Ghana are conducted for purification, dedication, thanksgiving, and reunion. One of their important functions is to maintain a link between the living and their ancestors, who are believed to guide all human activities (Silverman and Spezzacatena). The most important festival of the Dagomba is Damba, which is observed in all Dagomba villages where a paramount chief lives. The Damba festival begins during the third month of the Dagomba lunar calendar and lasts for seven days. The Damba festival began in the sixteenth century during the reign of the first Muslim Ya- Naa, or paramount chief, in Yendi, Ghana (Kinney 258). Islam was introduced to northern Ghana in the ninth century (“Pre-Colonial Period”). Therefore, today rituals of the Dagomba often combine both Dagomba and Islamic elements.

Fig. 8.10: Nico Spezzacatena, Ya- Na Yakubu Andani II, Dagomban Paramount Chief, 1999.

Fig. 8.10: Nico Spezzacatena, Ya- Na Yakubu Andani II, Dagomban Paramount Chief, 1999.

Damba is traditionally a time for the Dagomba to celebrate chieftainship. During the ceremony, chiefs participate in processions wearing elaborate regalia.

Lesser chiefs show homage to their superiors up to the Ya Naa, or paramount chief. The Dagomba gather and participate in a demonstration of respect and to hear singers articulate Dagbon oral history and sing praise songs to the chief. Damba is also an occasion for most people to exchange gifts and buy new clothes. Men dress in colorful, handwoven smocks called batakari that are designed for a style of dancing that includes many spins and twirls. Women wear expensive jewelry and a traditional, handwoven cloth wrapped around their waists. Damba also is a time for feasting, displaying horsemanship skills, and shooting rifles (Silverman and Spezzacatena).

This video, Damba Festival, highlights the events of the Damba festival. In the morning, the chiefs and other elders come to the palace where a bull is slaughtered according to an ancient ritual. Then, there is a procession of the chief and elders accompanied by drummers, gonje players, and other musicians. Later, the chief is led back to his home by singers and drummers. The end of the video features gonje singers. This particular Damba ceremony was held on July 3, 1999, in Yendi, Ghana. The largest Damba ceremonies are held here because it is the seat of the Ya Naa.

Ewe Music, Ghana

The Anlo-Ewe occupy southeastern Ghana and the southern parts of neighboring Togo and Benin. Dance-drumming is fundamental to Ewe culture as a way to focus community energy. The veneration of ancestors is a central part of this process because ancestors are considered a source of wisdom to be consulted (K. Ladzekpo).

Ewe dance-drumming music is polyrhythmic, usually combining 4/4 and 6/8 meters.

The music is accompanied by traditional songs and dancing. The drum language is secret and known only by the drummers (A. Ladzekpo). If there are no organized performances, community elders do not encourage the playing of drums, as it is seen as a disturbance when drums are played without the dancers and the entire musical ensemble. Open-air performances provide Anlo-Ewe youth the only opportunity to learn the music by listening and forming syllables from the drum language. During a performance, if lead drummers need a vacant instrument to be played, they beckon to any youth, traditionally a boy. If the chosen person already knows the part, he doesn’t need any instructions. If he doesn’t know the part, the lead drummer demonstrates the drum pattern and hands him sticks to play. If he plays correctly, he continues to play. If he fails, the lead drummer takes the instrument and gives it to someone else (A. Ladzekpo).

Fig. 8.11: Nico Spezzacatena, Anlo-Ewe dance-drumming ensemble, 1999.

Ewe music is played in an ensemble that usually features a lead drum, supporting drum, rattles, and bell. The lead drum is the atsimevu, which is carved from a log

Ewe music is played in an ensemble that usually features a lead drum, supporting drum, rattles, and bell. The lead drum is the atsimevu, which is carved from a log

and measures four to five feet in length. The drum head is usually made from the skin of a deer or antelope. It is played using a combination of sticks and hands.

Supporting drums include the sogo, kidi, and kaganu. The individual phrases of the supporting drummers are usually relatively simple. However, playing them in an ensemble is surprisingly hard.

The gankogui (bell) is the timekeeper and must be played steadily and without error.

Promising young drummers often are given the responsibility of playing the bell in an ensemble.

The axatse (rattles) are made from large gourds covered in a web of beads and are used to accent beats in the rhythm. The axatse players are usually also part of the chorus.

Visit the Virtual Drum Museumat Dancedrummer.com to see photos and demonstrations of the main instruments in an Anlo-Ewe dance-drumming ensemble.

Agbekor or The Great Oath

There are many different pieces found in the Anlo-Ewe musical repertoire. This section will examine Agbekor or “the great oath.”

In 1957, my father, Kofi Zate Ladzekpo, told me the meaning of “Atsiagbekor” or “Agbekor” drum language. Agbekor is Anlo-Ewe war music called “Atamga” meaning “the great oath.” It is the oath the ancestors took before they went to war to defend their tribe. The drum’s statements are admonishments from a father to his two sons who crave war. He plays calls on the lead drum for dancers to demonstrate what goes on in war. Agbekor expresses the enjoyment of life. –Alfred Ladzekpo

Agbekor is a classic call-and-response piece. It is practiced in seclusion and learned through direct teaching and guidance rather than listening/performing as in many other forms of Ewe music. Players learn long sequences, and the music is not strictly formalized. No one knows what is going to happen next (A. Ladzekpo).

Watch a video excerpt featuring “Atsiagbekor,” which is the opening section of “Agbekor.” This example features an excerpt from a performance played during the video Husunu’s Durbar and shows a traditional Anlo-Ewe ensemble, including a few American dance-drumming students who were invited to perform with the ensemble. The entire video depicts a celebration of the anniversary of the death of Husunu Ladzekpo, a revered leader of the Ewe people.

Listen to “Atsiagbekor”featuring lead drummer Agbi Ladzekpo.

Kwamivi Tsegah’s Funeral, Anyako, Ghana

This excerpt from the video KwamiviTsegah’sFuneralfeatures the Anyako Woeto

the group performing “Afa,” a piece always played at the beginning of a performance that is integral to getting blessings and ensuring that the performance goes well. Afa is the god of divination and a widespread religion that is open to anyone. This piece features the sogo as the lead drum, and almost every rhythm has a specific meaning, demonstrating a communication technique similar to the talking drum of the Dagomba (Iadada). The instrumentation in this performance includes sogo, kidi and kaganu, axatse, and the gankogui. The Woeto group’s colors for this performance are blue and white. Those who are not wearing those colors are from other areas of the community. They can be invited to dance, but cannot play the drums or lead songs (Liner Notes, Kwamivi Tsegah’s Funeral).

Another section of “Afa” is “Axatsevu.” Axatse is the Ewe name for rattle, and Vu means drum, hence rattle drum, a style of music dominated by rattles. “Axatsevu” is unique because it is the only Ewe piece with two songs happening simultaneously. The men and women have completely different song repertoires. The shoshi (the tail of a horse) is held by the song leader/s of the group. In most instances, there is more than one song leader so it doesn’t get boring. If the group is large, it is easier to identify the songs that the song leaders establish. When a person becomes a heno (song leader) of a group, a special horse tail is handed down in a private ceremony (Liner Notes, Kwamivi Tsegah’s Funeral).

Political Music in Africa: Fela Kuti and Thomas Mapfumo

Fig. 8.12: Nico Spezzacatena. Anlo-Ewe axatse ensemble, 1999.

Music in Africa has traditionally been a method of communication that includes the transmission of history, religion, genealogy, social and political issues, and more. Music often is used to offer commentary on contemporary society and politics, and many musicians in Africa rose to prominence in the struggle for independence from Great Britain’s colonization, which began in the 1960s. This section will discuss two of the most influential and popular political musicians in West Africa: Fela Kuti of Nigeria and Thomas Mapfumo of Zimbabwe.

Fela Kuti

Nigerian saxophonist, keyboardist, and vocalist Fela Kuti is a mythic figure in the African popular music tradition. In the late 1960s, Kuti traveled to the United States and was inspired by the civil rights movement (Music is the Weapon). He returned to Nigeria in 1971 and pioneered Afrobeat, a style of political protest music that combined funk, jazz, and highlife, a style of music originating in Ghana in the early twentieth century that combines indigenous melody and rhythm with the use of Western instruments. Through his music and public statements, Kuti challenged Nigeria’s military rulers and portrayed the suffering of the Nigerian people. He created a counterculture in the city of Lagos by using songs to criticize political leaders, declaring his compound an independent nation, and surviving numerous attacks by the Nigerian authorities (Veal 77-92). In 1979, he formed the Movement of the People (M.O.P.) political party and ran for president, although his party was disqualified from the elections by the ruling powers due to his outspoken criticism of political leaders. Kuti died in August 1997 due to complications from AIDS. Kuti “arguably combined elements of pure artistry, political perseverance, and a mystic, spiritual consciousness in a way that no other individual ever has” (Kambui). The fact that Kuti was able to flourish for three decades despite extreme pressure from authorities reflects the widespread affection many Nigerians held for Kuti and his work (Veal 243). Visit PBS’s Fela Kuti: Black President to learn more about Fela Kuti and hear samples of his music.

Thomas Mapfumo

Thomas Mapfumo was born in 1945 and is known as “the Lion of Zimbabwe” due to his use of music to boldly criticize political leaders in Zimbabwe and his role as both a developer and leader of traditional music of the Shona people, the largest indigenous group in Zimbabwe. As a youth, Mapfumo modeled American and English music, but later, in the 1960s, he began to translate protest songs into the Shona language. In 1972, Mapfumo formed the Hallelujah Chicken Run Band and began to explore traditional Shona folk music, which features the mbira, a type of thumb piano that is the main instrument in Shona music. Together with the band’s guitarist, Joshua Dube, Mapfumo transcribed the tonal scale used by the mbira for the guitar and added traditional drums (Eyre).

Mapfumo’s lyrics reflected the concerns of his people, such as the hardships suffered in rural areas, young men fighting in the bush, and a rising outrage against white rulers who systematically devalued and attacked traditional Shona culture. Mapfumo named his new music style chimurenga, the Shona word for “struggle” and the name taken by guerrilla freedom fighters in Zimbabwe (Eyre).

Mapfumo was seen as a troublesome political leader by the white regime in Zimbabwe that tried to block the release of his music and forbade playing Mapfumo’s music on the radio. He was imprisoned without trial, which led to violent protests that eventually led to his release. After Zimbabwe’s independence, the ban against Mapfumo’s music was lifted and in 1980, his group performed with Bob Marley and the Wailers at an event marking Zimbabwe’s independence. Mapfumo continued to write politically motivated music that criticized the corruption and misuse of power by the post-colonial leaders of the newly independent Zimbabwe.

In the 1990s, Mapfumo changed his focus to criticizing the new leaders of independent Zimbabwe, who he believed had failed the people. By the summer of 2000, the conditions in Zimbabwe had deteriorated badly, partially due to Robert Mugabe’s aggressive and violent policies. Mapfumo’s music was unofficially banned from state-controlled television and radio. Due to this pressure from the government, which included threats and false charges of theft, Mapfumo relocated his family to the United States in 2000, though Mapfumo continued to return to Zimbabwe despite the risks until 2004 to continue to speak out against corruption and greed within the political leadership (“Thomas Mapfumo”). Today, Mapfumo continues to sing and speak out for the poor and disenfranchised people of Zimbabwe.

Watch this video of Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited performing “Moyo

Wangu” in 1994.

North Africa and the Middle East

“What we call music in our everyday language,” according to the great master of the Sufi sect of Islam Hazrat Inayat Khan, “is only a miniature, which our intelligence has grasped from that music or harmony of the whole universe which is working behind everything, and which is the source and origin of nature. It is because of this that the wise of all ages have considered music to be a sacred art. For in music the seer can see the picture of the whole universe …” (Shelquist).

Figure 8.13: Justinian-of-Byzantium, Middle East map in full, 2011. In this map, the Middle East is highlighted in green.

The origins of Arabic music are in the distant past and emerged during pre-Islamic times in the Arabian Peninsula. Many elements of music, such as the tonal system, rhythmic patterns, musical forms, compositional techniques, and performance practices, are essentially the same in all Arab countries (Touma 8).

Arabic Melody and Rhythm

Fig. 8.14: Aleppo Music Band, 1915. This photo depicts a traditional Arabic musical ensemble.

Melody in Arabic music is quite different from Western melodies. Arabic music most commonly uses scales consisting of seventeen, nineteen, or up to twenty-four equal quartertones—smaller intervals than those found in Western music, half the length of half-steps or semitones. Quartertones are also sometimes referred to as microtones. Arabic melody is based upon over fifty-two modes called maqamat, which means “place or situation.” A maqam, or melody, utilizes selected notes from a specific maqamat with a certain tendency of movement. A maqam is “something more than a scale, yet something less than a tune” (Spencer). An Arabic melody must use the notes of a specific maqam and incorporate the melodic fragment into the melody line with an emphasis on ornamentation, a technique in which a musical note is embellished by adding notes or changing the rhythm. The maqam helps create the mood for a particular piece of music (Touma, preface).

Arabic music has a monophonic texture with one central melodic line and does not utilize harmony. When multiple instruments play, one instrument carries the primary melody with the other instruments layering melodies and rhythms over it. This is different from

Western music usually includes harmony and chords. Soloists in Arabic music often improvise during a performance. This structure reflects Arabic music’s nomadic traditions and its use of caravan songs. Traditionally, Arabic music is not notated, rather it is learned by listening (“The Arabic Maqam”).

The rhythm of Arabic music can be quite complex with patterns of up to forty-eight beats called iqa’at. Arabic rhythms typically include several downbeats (dums) or principal accented beats, upbeats (taks) or unaccented beats that precede the downbeats, and rests or silences. The dum, or downbeat, is usually a deeper tone created from striking the center of the drum. The tak, or upbeat, generally has a higher and crisper timbre and is created by hitting the drum near the rim. Much like Indian music, which will be explored in the next section, Arabic musicians usually play a basic pattern ornamented with improvisations that can be compared to the performance style found in jazz (Montford).

Arabic music performance traditionally reflects the response of the audience, which is expected to react during a performance verbally or with applause. If an audience is quiet, this often means the audience is disinterested or dislikes the music. The audience is an active participant in determining the length of the performance, and it shapes the music by encouraging musicians to repeat a section or move to the next one (Danielson).

Classical Arabic music is based upon the takht, a small ensemble consisting of the

oud, qanoun, nay, violin, and percussion without vocal accompaniment (Dimitriadis).

oud, qanoun, nay, violin, and percussion without vocal accompaniment (Dimitriadis).

An oudis a pear-shaped instrument with two to seven strings with its origin in ancient Egypt (Dimitriadis). The qanounis a plucked zither with strings made of gut or nylon. The nay is an open end-blown flute traditionally made from bamboo that can be either vertical or horizontal. The main Arabic percussion instrument is the riq, a small tambourine with its

head made from goat or fish skin. Around the frame of a riq are paired brass cymbals that create a jingling sound (“Arabic Musical Instruments”). Each region in the Arab world has its own distinctive style, instrumentation, rhythmic pattern, modal structure, and

performance technique; these create an art form that extends across a large geographic area and an artistic a tradition that evolves while maintaining its traditional heritage.

Fig. 8.15: Catrin, Egyptian riqq, 2006. This photo depicts a traditional Arabic riq.

Listening Examples

- “MaqamBayati” (played on the oud)

South Asia

Classical Indian Music

Indian music has religious roots. Indian mythology asserts that music was brought to the people of India from the celestial plane and is used to free the self (atman) from mind and matter. This enables a merger between

Fig. 8.16: TUBS, India in Asia, 2011. This map of Asia depicts the country of India, which is highlighted in red.

the atman and the cosmic forces of the universe. This concept is expressed in the following passage from The Natya Shastra, an ancient Indian text on the performing arts:

Once, a long time ago, during a transitional period between two Ages it so happened that people took to uncivilized ways, were ruled by lust and greed behaved in angry and jealous ways with each other and not only gods but demons, evil spirits, … and such like others swarmed over the earth. Seeing this plight, Indra [the Hindu God of thunder and storms] and other Gods approached god Brahma [God of Creation] and requested him to give people a toy (Kridaniyaka), but one which could not only be seen but heard, and this should turn out a diversion (so that people would give up their bad ways). It was determined to give the celestial art of sangeet to mankind. (Courtney)

This was the origin of sangeet, a Sanskrit term used for the traditional Indian performing arts, which include vocal music, instrumental music, and dance. The aesthetic basis of sangeet is formed by the nine fundamental emotions from which all complex emotions can be produced. This reflects Hindu concepts about how mood and its creation of energy can affect the mind and body. Through classical Indian music, every feeling and emotion can be expressed and experienced. The purpose of classical Indian music is to activate energy centers (chakras) and connect humans to higher levels of consciousness (Shankar).

In India, music is seen as a spiritual discipline that leads to self-realization and enlightenment. This is based upon the traditional teaching that sound is God, or that vibration is the source of the universe. This belief is known in Sanskrit as “Nada Brahma”: “the world is sound.” In texts from the Vedic culture of ancient India, there are two types of sound. One is a vibration in the celestial plane, known as the “Unstruck” sound (Anahata Nad), which can only be heard by enlightened yogis. The other sound, known as the “Struck” sound

(Ahata Nad), is the vibration found in the earthly realm. This includes sounds in nature and manmade sounds, both musical and non-musical (Shankar).

The introduction of music to humans by the divine was the first step; it then had to be taught. The inherent divine qualities of Indian classical music require the following prerequisites:

- Guru (teacher): Indian music is orally transmitted and is considered the highest form of knowledge. A guru is essential to the learning process.

- Humility: Indian classical music is a sacred art requiring not only technical but also spiritual development. If a student lacks humility, then he or she will not be able to learn.

- Discipline: Music is a highly evolved and complex art form, which requires disciplined practice. This discipline applies to both technical and spiritual learning. Discipline is essential to mastering Indian classical music (Courtney).

Basic Components of Classical Indian Music

Indian classical music typically has three layers:

- Drone: The drone is an unchanging tone or tones that underlies the melody. The drone marks the tonal center of a piece. Usually, a plucked tambura or a sruti box plays the drone (a sruti box is a type of organ that creates its sound using hand-pumped bellows that force air through reeds) (Titon and Fujie 212).

- Raga: A raga is a melodic form upon which the musicians improvise. Ragas are not based upon harmony, counterpoint, modulations, or other melodic elements found in Western music. A raga is based upon a particular scale and specific movements of

the melody. One raga is differentiated from another by subtle differences in the order of the notes, or omission or emphasis on a dissonant note, slide, or microtone.

Ornamentation and intonation are central aspects of the performance of a raga. The phrase “Ranjayathi iti Raga” is found in ancient Indian texts. This description of ragas is translated as “that which colors the mind,” and is an expression of the inner spirit of an artist (Titon and Fujie 212).

- Tal: The rhythm and drumming in India are among the most complex in the world.

Many common rhythmic patterns are centered on repeating patterns of beats. Drummers memorize hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of rhythmic patterns. Talas can range from three to one hundred eight beats and are played in many different complex meters (9, 11, 13, 17, 19). The most advanced musicians play some rhythms on only rare occasions. Playing a tal requires a constant calculation to determine how different patterns fit with the tala cycle. These rhythms can be expressed vocally as well, which is called solkattu. Indian classical rhythms differ in how the beats are divided and accented. They are expressed with subtle variations, such as the use of pauses, accelerandos, and ritardandos, and are reflective of the infinite variety represented in the Hindu faith (Titon and Fujie 214).

It is estimated that there are over six thousand ragas and that up to ninety percent of Indian classical music is improvised. Ragas are used to create psychological states and are associated with times of day, seasons, planets, moods, or certain magical properties. This divine quality of music is expressed through nad siddha, the ability to perform miracles by playing specific music (Shankar). Tansen, a musician from North India who lived in the sixteenth century, was the most famous miracle-making musician and was said to be able to create fire and rain through the singing of specific ragas (Courtney). Ragas are utilized for myriad mystical purposes, including healing the sick, affecting the weather, summoning spirits, charming cobras, and many more. It is not possible to notate a raga because it is never the same twice: there are many variations in length, rhythm, intonation, and embellishment.

The structure of Indian Classical Music

A traditional recital of Indian classical music begins with the alap, a section that explores the melody of the chosen raga without a clearly defined rhythm. After this slow and introspective beginning, the music moves onto the jar. This is when the rhythm enters and develops without the accompaniment of a drum. This section evolves into the gat, which is the fixed composition of the raga. In the gat, the drum joins the main structure of the raga and the tal. The gat becomes the basis for improvisation; musicians are free to improvise within the basic structure of the raga and tal. It requires years of practice and discipline to be an effective improviser (Shankar).

When performing Indian classical music, musicians take into consideration the setting, the mood of the audience, the time allowed, the time of day and season, and other factors. The goal is to maximize that particular moment. Musicians have great flexibility in shaping a performance, and concerts can last several hours (Shankar). It is also important to recognize that the interpretation and expression of the raga and tal are not the same throughout India. Today, there are two main traditions within Indian classical music: the South Indian Carnatic tradition and the North Indian Hindustani tradition.

Carnatic Music, South India

The Carnatic tradition reflects a more orthodox Hindu tradition. All Carnatic music is based upon a song. Even if there is no vocalist, the words are known to those with an understanding of the music. The first composers of the Carnatic tradition served as musicians to the ancient raja courts and are from the Brahmin caste. The caste system is a traditional method of stratification used in India. Membership in a caste is hereditary.

Brahmin is the highest caste and its members are often priests or scholars.

The main instruments of the Carnatic tradition are the veena, mridangam, and

The main instruments of the Carnatic tradition are the veena, mridangam, and

tambura. The veena is an instrument with four playing strings and three drone strings. Along the neck are brass frets set in the wax that are curved to allow the player to bend the strings. There are many complex fingerings, slides, and ornaments utilized by the musician to express the character of a specific raga.

Fig. 8.17: Gringer and Sreejithk2000, Veena, 2010. Fig. 8.18: Domtw, Mridangam, 2010.

The mridangam is a barrel-shaped double-headed drum. The heads of the drum are made from leather and are connected to the body of the drum by leather straps attached to moveable tuning pegs. The lower (untuned) head has a circle of soft wheat paste in the center that creates a booming sound when struck. The higher head is tuned to the tonic

note of the raga, which is the central note upon which the raga is based, and has a hard black spot in the center that creates a high-pitched, sharp sound. The complexity of the drumheads combined with the sophisticated fingering techniques used by mridangam players makes it possible to play more than fifteen distinct sounds through varying combinations of drum strokes.

The tambura is a plucked instrument with four strings. It is held vertically and functions as a drone. It is tuned to the tonic note of the raga, or the natural fourth or perfect fifth above or below the tonic note.

Listen to “Raga Narayani” performed by D.K. Jayaraman and D.K. Pattammal, traditional Carnatic singers (second song on the list). Please note that for this chapter, transcripts of song and music lyrics are not necessary to gain an understanding of the material.

Hindustani Music, North India

Fig. 8.19: Jan Kraus, Sitar, 2008.

The North Indian Hindustani style of music utilizes the same ragas and talas but has been more influenced by Persian and Islamic culture than the Carnatic style. The main instruments found

in Hindustani music are the sitar and tabla.

in Hindustani music are the sitar and tabla.

The sitar is a complex and beautiful string instrument. A sitar has eighteen strings, including several drone strings located under the moveable frets, which are bars set across the fingerboard on the neck, that vibrate sympathetically when the main strings are played. The drone strings are also periodically struck to provide an atonal base (atonal music is music without a tonal center). Most of the playing on a sitar is done on one string.

The tabla is a set of two drums, one of which is smaller than the other. Tablas are tuned by tightening the pegs and strings. Wheatpaste in the center of one drum produces a deep, booming sound.

Fig. 8.20: Ankitchd26, Historical Musical instruments, 2011. This photo depicts the tabla, the traditional drum played in Hindustani music.

Listening Examples

“TablasoloinTeentala” Nikhil Ghosh, tabla

“RagaKaushiKanada” (second track on list) Nikhil Banerjee, sarangi

Bollywood Music

The rise of Hindi film music in the 1930s influenced many styles of music around the world. One of the most prolific Indian film music styles is Bollywood. This popular music, written and performed for Indian cinema, is a modern evolution of traditional Indian forms of entertainment that feature music as a central aspect of the performance (Wohlgemuth).

Rather than singing themselves, the film actors in Bollywood films usually lip-sync to music sung by accomplished singers. Bollywood music soundtracks account for the majority of popular music sales in India. In fact, most Indian people go to the movies for songs (“Bollywood Music”). Bollywood music has a nationalistic quality, representing India as a whole and incorporating styles from many Indian musical traditions (Carnatic and Hindustani classical music, religious and folk music) (Wohlgemuth). Today, the Bollywood film industry consists of many genres and styles.

For an example of Bollywood film and music, watch an excerpt from the Bollywood film, Hum Saath Saath Hain. Please note that for this chapter, transcripts of song and music lyrics are not necessary to gain an understanding of the material.

Southeast Asia

The Southeast Asian country of Indonesia is home to myriad musical traditions. Over thousands of years, some of these forms remained indigenous and localized, whereas others evolved through interaction with neighboring, and sometimes invading, cultures to produce various syncretic styles (syncretism in music is a combination of musical elements from individual cultures that creates a new style of music).

Fig. 8.21: Anonylog, Indonesia, Bali, 2008. This photo depicts the archipelago of Indonesia. The island of Bali is highlighted in green.

Balinese and Javanese orchestral music represent some of the most complex styles of music found in the Indonesian archipelago. This section will explore the more lively style of Balinese orchestral music called the gamelan.

Balinese Music and Dance

Almost everyone participates in artistic activities in Bali. The arts are directly connected to the Bali-Hindu religion, a religion based upon indigenous practices combined with Hinduism and elements of Buddhism. Dances and dramatic performances are seen as an integral part of Balinese religion and culture and serve as an expression of devotion to the gods and as a method of reinforcing cultural values. The essence of Balinese culture rests in the village, where most ceremonies are held. Each village in Bali has differing ceremonies, performance techniques, and specialties with seemingly endless and mind-boggling variations.

The main type of music found in Bali is gamelan music. A gamelan is an orchestra comprised of a variety of instruments including drums, gongs, and cymbals. These instruments are ornately decorated with symbols and gods from the Bali-Hindu religion and mythology. The instruments are tuned in pairs (male and female) with one tuned slightly higher than the other to create a shimmering sound. Instruments are regarded as highly sacred and are played only after proper offerings and rituals have been completed. The instruments serve as the most important elements to reach God.

Fig. 8.22: Cathy Silverman, Village gamelan, Luwus, Bali, 2008.

Balinese music is constantly evolving with old styles falling out of favor and new styles emerging. There are seemingly infinite styles of gamelan music found in Bali, an island only two hundred miles wide. These include semar peguliligan (the love gamelan), gambuh (a nine-hundred-year-old style featuring very large vertical bamboo flutes) (Spies and de Zoete 75), jegog (gamelan instruments made from bamboo), gong gede (prevalent in the early 1900s) (Brunet), kebyar (a twentieth-century style), the marching gamelan, and many, many more. The most sacred of all gamelans is gamelan selonding, which is the oldest type of gamelan dating back two thousand years, (Lewiston and Burger) and is made from iron rather than the bronze found in modern gamelans (Bakan 355).

Balinese gamelan music is playful and frenetic with sudden stops and starts, dramatic changes in volume, precise syncopated playing, and complicated counterpoint. A gamelan has no real conductor; the music is usually led by one or two experienced drummers who control its pace and signal changes to the musicians. Members of a village gamelan orchestra are not professional musicians—they have normal family responsibilities, jobs, and village obligations.

Gamelan music is played from memory, which is quite extraordinary considering the length and complexity of many gamelan compositions. Music is heard from birth and is learned through listening and repetition. The musical parts interlock, which creates the impression that the music is performed more quickly than it actually is. Gamelan melodies are based upon two primary equal temperament scales: slendro (a five-note pentatonic scale) and pelog (a seven-note scale). According to a legend of the Bali Aga, who are the original inhabitants of Bali, the gods provided the first gamelan notes.

Gamelan Instruments

There are many types of gamelan instruments—too many to address here— however, we will highlight the instruments commonly found in a Balinese gamelan

There are many types of gamelan instruments—too many to address here— however, we will highlight the instruments commonly found in a Balinese gamelan

Fig. 8.23: Cathy Silverman, Gamelan factory, Tihingin, Bali, Indonesia, 2005.

Fig. 8.23: Cathy Silverman, Gamelan factory, Tihingin, Bali, Indonesia, 2005.

orchestra, The most common type of gamelan ensemble consists mainly of gongs and genders, a type of xylophone instrument that is struck with mallets. Genders have bronze keys suspended over bamboo resonators and are tuned in pairs, each at a slightly different frequency, which creates a shimmering sound when played together. The gongs are also made from bronze, although in the past the gongs and genders were made from iron. There are three types of gongs: single-hanging and lying gongs played by one person that accent the central melody, sets of gongs on a frame played by one the person that plays the central melody, and larger gong sets played by two to four people used to embellish the central melody.

Fig. 8.24: Cathy Silverman, Balinese gongs, 2008. Fig. 8.25: Cathy Silverman, Balinese drummers, 2005.

The gamelan orchestra is conducted by the kendang, a pair of double-headed drums, one with a higher pitch than the other. The gamelan also often includes the suling (bamboo flutes), a rebab (a two-string violin), and the chang-chang (a set of cymbals). Gamelans are tuned to themselves and therefore instruments from one gamelan cannot be used in another gamelan.

Balinese music has a remarkable quality: the lower instruments in a gamelan ensemble play lower-pitched, slower tempo parts, while the higher instruments play higher-pitched, faster parts. This interestingly reflects the way sound waves resonate scientifically (lower frequencies resonate in long, slow waves, whereas higher frequencies resonate in short, fast waves). How the ancient Balinese knew this without the use of scientific equipment is a mystery yet to be solved.

Watch a gamelan performance at PitraYadnya, a Balinese funerary ceremony.

Listen to “Gamelanselonding” from the Bali Arts Festival.

In addition to the more common bronze and iron gamelans, there are also gamelans made from bamboo called jegog that are traditionally found in Western Bali.

Fig. 8.26: Cathy Silverman, Jegog instruments, 2010.

Listen to “Jegog” performed by the Surya Metu Reh ensemble, Negara, Bali.

Genjek

Genjek is a unique form of music found in Bali. Genjek is the vocalization of gamelan music, using voices instead of instruments. It is a secular style of music, often performed at parties and social gatherings. Genjek singers sit in a circle and intersperse the genjek songs with the drinking of arak, a type of liquor made from palm.

Listen to “Genjek” from a performance in Candidasa, Bali.

The Relationship Between Balinese Music & Dance

Dance and music are inextricably connected within Bali-Hindu culture and are performed primarily as an offering to the gods. Balinese dances bring to life ancient stories.

There are hundreds of accompanying dance styles in Bali, including Sangyang trance dances, Legong (young girls’ dance), Baris (young men’s dance), Calonarang, Joget, Janger, the popular Barong & Rangda (a dance that restores the balance between good and evil), and dozens more. Of particular interest are masked dances, such as Topeng and Jauk. These two dance styles are unique: the dancers lead the gamelan, rather than the gamelan leading the dancers as is found in other forms of Balinese dance. Topeng and Jauk, both forms of masked dance, are more spontaneous and improvised than other forms of Balinese music and dance.

East Asia

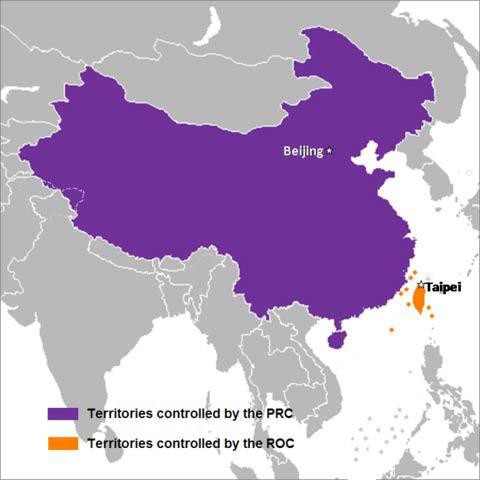

Fig. 8.27: Hmh 2001, China map updated, 2011. This map of China depicts both the PRC (People’s Republic of China) and the ROC (The Republic of China, also known as Taiwan).

The music of East Asia has a long and varied history. Traditionally, the Chinese believed that sound influenced the harmony of the universe. Interestingly, one of the first duties of the emperor in a new dynasty was to seek out and establish the true standard of

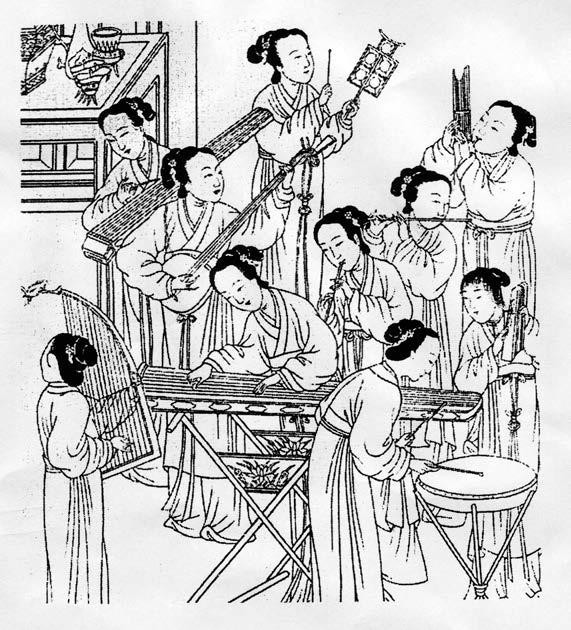

8.28: Bagdadani, Ancient Chinese instrumentalists, 2008.

the pitch for the dynasty. Harmony within Chinese society, both spiritual and communal, was not determined by economics or other material measurements but was based upon music. This represented the philosophy of Confucius, who believed that music was a means of controlling negative emotions, rather than merely a form of entertainment. Music was thought to have the ability to connect humans to higher levels of consciousness through the principle of harmonic resonance: “right” music had a harmonious effect on people and their environment, maintaining a balance between the physical and spiritual worlds and creating health, harmony, prosperity, and peace. “Wrong” music, however, would create illness, economic problems, and war. In China, music is seen as having the ability to affect the human body and psyche, leading to personal development and later, spiritual enlightenment. Music represents a connection and mode of communication between heaven and earth (Eaton).

Most Chinese music is based upon just intonation, compared to the equal temperament system of tonality developed in the Baroque era that is utilized in Western music. The difference between these two types of tuning systems is that just intonation reflects the way sound Fig.

resonates naturally and therefore is harmonic with the natural environment. In contrast, equal temperament is essentially a man-made system developed in Europe in the early eighteenth century that is harmonic within itself but is dissonant (or clashes) with the harmonics of the natural environment and the basic resonances of the human body. The Chinese have always refused to completely adopt the equal temperament scale because they believe disharmonious music can cause problems in society and nature (Eaton).

The Pentatonic Scale

The primary scale used in traditional Chinese music is the five-tone, or pentatonic scale, which is a scale found in many types of sacred music around the world. Five is a significant number in Chinese cosmology, representing the five elements of the visible world: the four elements and the center. This concept of the number four is reflected in the four cardinal directions, the four seasons, which arise from the fifth celestial element (Akasa), or the central principle (Eaton).

The five notes of the pentatonic scale, according to Chinese theory, are the only ones with the ability to create true harmony on the physical plane. Comparisons can be made between musical harmony and the proportions of sacred architecture, and those of the human body, colors, time, and concepts found in fractal geometry (Winn). Here is an excellent example of a pentatonic scale demonstrated by Bobby McFerrin at the World Science Festival in a symposium entitled “Notes and Neurons: In Search of the Common Chorus” (transcript available).

Melody and tone color are prominent expressive features of Chinese music, with great importance placed on the proper articulation of each tone (Fang). Traditionally, Chinese instruments are classified according to the materials used: stone, metal, wood, clay, bamboo, and other natural materials. The oldest instruments in China include flutes, zithers, panpipes, mouth organs, and percussion instruments such as bells, gongs, clappers, and drums. A flute carved from the wing bone of a crane found in China dated c. 7000 BCE is the world’s oldest still playable instrument.

Melody and tone color are prominent expressive features of Chinese music, with great importance placed on the proper articulation of each tone (Fang). Traditionally, Chinese instruments are classified according to the materials used: stone, metal, wood, clay, bamboo, and other natural materials. The oldest instruments in China include flutes, zithers, panpipes, mouth organs, and percussion instruments such as bells, gongs, clappers, and drums. A flute carved from the wing bone of a crane found in China dated c. 7000 BCE is the world’s oldest still playable instrument.

Classical Chinese Court Music

Chinese music is not a single, unified tradition, but rather reflects the many different ethnic groups found in China. An example is the traditional music of Amoy, a city in the southeastern province of Fujian situated on the Taiwan Strait. The traditional music of Amoy is known as nan-kuan (southern pipes) and is believed by Chinese musicologists to have preserved a type of classical Chinese court music that reached its peak during the Tang Dynasty (Lieberman).

Fig. 8.29: Ian Kiu, Tang dynasty circa 700 CE, 2007.

Listen to “Fei Fei Shih Shih (Rainy Weather)” (number three on the list). This piece features the hsiao (or xiao), a vertical bamboo flute that traditionally has five holes, although today it often has six holes. Performers must master dozens of complicated fingerings to successfully play the hsiao. This composition also features the pipa, a pear-shaped lute with a crooked neck and four to five strings that are plucked. The pipa is a commonly used solo instrument in ensembles and Chinese orchestras (Lieberman).

Central Asia

Fig. 8.30: Voodooisland, Tuvan People’s Republic, 2010.

Fig. 8.30: Voodooisland, Tuvan People’s Republic, 2010.

This image depicts the Republic of Tuva, which is highlighted in green.

Central Asia includes some of the oldest forms of music found on earth, dating back several thousand years. Traditional music in central Asia is based upon nature and reflects an ancient shamanistic tradition in which all things and phenomena have a spiritual counterpart. For example, the spirituality of rivers and mountains manifests through their physical shape, but also through the sounds they produce. Humans are believed to have the ability to access the energy (and consciousness) of nature, assimilating the power of nature by imitating its sounds, a practice called “sound mimesis.” There are many types of stylistic variations used to imitate the calls and other sounds made by wild and domesticated animals (Levin and Edgerton).

Khöömei – Throatsinging of Tuva

For the semi-nomadic herders living in Tuva, a central Asian republic in southern Siberia, the natural soundscape inspires a form of music that resonates with the environment creating a blend of natural and human sounds. Of the many ways Tuvans use sound to interact with the environment, one of the most distinct is their use of throat singing, a remarkable technique found primarily in central Asia in which one vocalist produces two or more separate tones simultaneously. In Tuva, singers state that the origins of this method can be traced far back in history; shamans used it and a variety of sounds as tools for spiritual and physical healing (Levin and Edgerton).

In Tuvan throat singing, one of the tones produced is a low, sustained drone and the other tone is a series of higher pitches that could be described as representing the song of a bird, the gurgling of a mountain stream, or the rhythm of a cantering horse. The term for this type of singing is called khöömei, which is the Mongolian word for throat. Throat singers are able to manipulate their vocal folds in a way that enables them to create a whistle-like pitch while simultaneously creating the underlying low drone (Levin and Edgerton).

Fig. 8.31: Kovitz, Johanna, Igil front view, 2007.

This photo depicts the igil, a traditional Tuvan string instrument.

Rather than being taught formally, khöömei is learned like a language. There are many styles found within the khöömei tradition, including sygyt, kargyraa, and barbang-andyr. Khöömei is sung in separate phrases with pauses between each phrase. Tuvan musicians conceive of each phrase as an independent sonic image.

The pauses give singers time to listen to the ambient sounds in the natural environment and create a sonic response (Levin and Edgerton).

Tuvan Instruments

There are also many types of instruments used in Tuvan music. The tungur is a frame drum used also in shamanic rituals. The igil is a fiddle with a horse head at the top of the neck; it has one or two strings made from horsehair. The doshpuluur is a three-stringed instrument with an unfretted neck that is plucked or strummed.

The xachyk is a rattle made from bull testicles, and the tuyug is a percussion instrument made from horse hooves. The xomuz is a. This photo depicts the jaw harp used to recreate natural sounds like water, and human sounds, including speech. Good xomuz players can encode spoken language in a way that can be understood by an experienced listener (“Tuva: Among the Spirits”).

Fig. 8.33: Tosha, Kamuz, 2007. This photo depicts the xomuz, also known as a jaw harp.

Today, khöömei is performed both as it always has been in its natural environment, and also in concerts and doshpuluur, also known as a horse head fiddle. competitions. A wonderful film entitled Genghis Blues documents a throat singing competition in Tuva. It features Paul Pena, a famous blues singer and one of the few Westerners to master the throat singing technique.

Here is an example of sygyt performed by Kaigal-ool Kovalyg, a member of the traditional Tuvan throat singing group Huun-Huur-Tu (transcript available). Also, listen to an example of kargyraa, a form that creates undertones rather than overtones, performed by the same group.

Native American Music

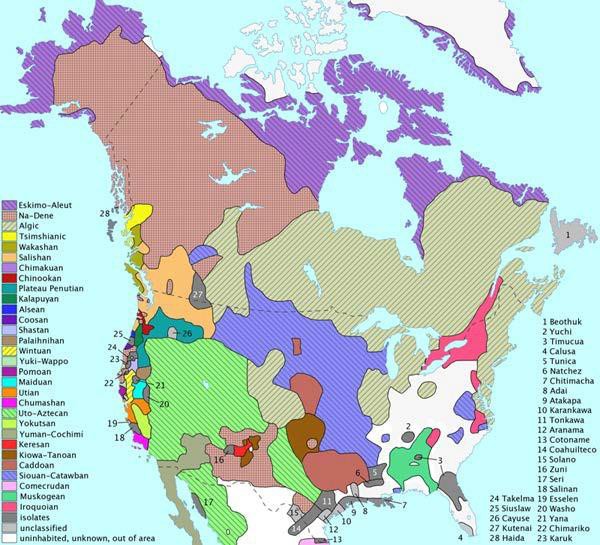

Fig. 8.34: Ish Ishwar, Languages Native America, 2005. This photo depicts the many Native American languages found in North America.

The indigenous music of Native Americans is both fascinating and diverse: it represents over five hundred distinct tribes, each with its own unique musical tradition. As Natalie Curtis states in The Indians’ Book: Songs and Legends of the American Indians, “To the Indian, song is the breath of the spirit that consecrates the acts of life” (xxiv). Throughout North and Central America, song, ceremony, and prayer are central aspects of healing ceremonies conducted by Native American shamans and medicine men. In the past and continuing today, music and drama are an inseparable part of the religious, social, and military activities of Native American people. Music and dance are used to celebrate the relationship between humans, nature, and spirits, and traditional rituals are used to connect the present, past, and future.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the U.S. government’s official policy towards Native Americans has forced assimilation. Children were taken from their families and placed in schools with the goal of assimilating the children into white American culture. Native children were not permitted to speak their indigenous languages, which included singing their culture’s songs and music. This has had a significant detrimental effect on the survival of Native American musical traditions over the course of time (Honani).

Native American Instruments

Native American Instruments

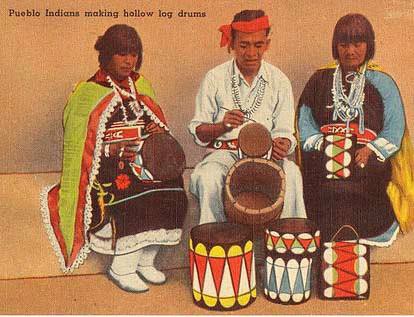

Fig. 8.35: Beesnest McClain, LACMA Tairona brown ware ocarina, 2009., This photo depicts a zoomorphic clay flute. Fig. 8.36: Alfred Mc Garr, Pueblo Indians making hollow log drums, 1930-1945. Fig. 8.37: Franco Altirador, Antlers of fallow deer, 2007.

This photo depicts deer antlers traditionally used as percussion instruments by a variety of Native American peoples.

The voice is the central instrument in traditional Native American music, often accompanied by dance. Vocals generally are powerfully rhythmic, sometimes featuring shouts and animal calls. Rattles, drums, and flutes are also important instruments within the Native American musical tradition. Some of the instruments include turtle shell rattles, zoomorphic (representing an animal form) clay and bone flutes, gourd trumpets, log drums, and deer antlers.

Most Native American instruments have symbolic meanings, such as the rattle. The body of the rattle, often a gourd, represents the female aspects of nature. The handle represents male attributes. When joined together, they represent the unity and transcendence of dualism (one thing having two parts, such as night and day or male and female). Stones are generally put inside the gourd to create a rattling sound; these too have symbolic meaning. Worldwide, stones are believed to be receptacles for ancient wisdom.

This is because stones are the oldest objects on the planet and are thought to have been absorbing the energy around them for millions of years. It is believed that when a rattle is shaken, the sound created by the stones hitting each other is the material manifestation of the release of ancient wisdom (Honani).

Fig. 8.38: Tommy Wildcat, Turtleshell rattle, 2009.

The following example, “Grass Dance Song,” features the traditional singing of the Blackfoot tribe, which has traditionally lived next to the Rocky Mountains in Montana (“We Come From Right Here”). Dancing is a central aspect of Blackfoot spirituality. The Grass Dance expresses how traditionally young men would trample the grass before setting up camp; this dance demonstrates how to do so (“The Blackfoot: Dancing”).

Fig. 8.39: John C. Grabill, Indian Warriors, 1890. This photo depicts traditional Blackfoot dancers after a performance of “Grass Dance.”

Watch “Men’sGrassDance” performed by Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park Dance Group.

Powwow Drumming

The term “powwow” was originally used to refer to healing ceremonies. Over time it has come to refer generally to Native American gatherings. In a Native American context, the word “powwow” today refers to a secular event featuring singing and social dancing by members of various tribes.

Although many elements of the powwow remain traditional, today they are dynamic expressions of Native American identity and pride, serving as pan-tribal events featuring a variety of songs, dances, games, and contests. Although secular in nature, there is always an observance of spiritual elements. Participants come to powwows to reflect and pray, as well as to dance and compete (“What is a Powwow?”).

Fig. 8.40: Danielle Lorenz, Colors of the Sun, 2010. This photo depicts a powwow dancer in a traditional costume.

Listening Example

“OwashtinongChungamingDrumming”

Fig. 8.41: Dori, Native American PowWow, 2008. This photo depicts the feather headdress of a powwow dancer.

Mayan Music of Mexico & Central America

The Mayans were an advanced civilization living in Mesoamerica that can be traced back to approximately 1500 BCE. They are known for their complex calendar system and sophisticated pyramids. One cannot explore the music of the ancient Maya without addressing the astounding sonic attributes of Mayan architecture. For example, El Castillo pyramid at Chichen Itza in Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula has interesting acoustic properties. As people climb the colossal stairs of the pyramid, their footsteps create sounds that mimic the sound of falling rain. It has been recently theorized by researchers that these sounds were created and used to communicate with Chac, the Mayan rain god (Franks).

Fig. 8.42: Kmusser, Maya map, 2006. This photo depicts the locations of ancient Mayan archeological sites.

Scientists have also demonstrated that the tiered steps of Castillo create sounds that mimic the quetzal bird, a sacred bird in Mayan mythology. Clapping at the base of the pyramid creates this chirping sound. An analysis of the pyramid’s acoustics demonstrated that the chirping sounds were made by a variety of complex sonic factors, such as a natural acoustical filter created by the pyramid’s steep steps (Ball). Also, a person standing on the top step speaking at a normal volume can be heard by those on the ground at some distance. This attribute is also found at one of the pyramids at Tikal and among its various Mayan ball courts that have survived to modern times (“The Acoustics of Mayan Temples”).

The remarkable sonic attributes of Mayan architecture reflect technology and understanding that continues to baffle researchers. Even today, there is no clear understanding of how Mayan buildings were constructed to create sound.

To hear one example of this amazing acoustical phenomenon, listen to this recording of a “Quetzal chirp” created by clapping at the base of the Kukulkan pyramid at Chichen Itza.

The Maya maintain a strong connection to their ancestors and history through rituals and mythology. Fiestas, dancing, and traditional music remain

Fig. 8.43: Brian Snelson, El Castillo, 2007. This photo depicts El Castillo, an ancient Mayan pyramid located at Chichen Itza in the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico.

central aspects of Mayan culture. There are many ceremonies and celebrations occurring throughout the year, during which dancers, singers, and musicians wear elaborate costumes and masks (Franco). This section examines two popular dances found in the highlands of Guatemala where Mayan traditions are still observed.

Fig. 8.44: Frank Vassen, Resplendent Quetzal, 2007. This is a photo of a quetzal bird, a sacred bird in ancient Mayan religion. Fig. 8.45: Ptcamm, Quetzalcoatl, 2007. This is a picture of a sixteenth-century drawing of Quetzalcoatl, a central god in ancient Mayan religion.

“Palo Volador” is an extremely old, and rare, dance. In this dance, participants swing from a sixty-foot pole reenacting the descent of the Hero Twins into the Underworld as described in the sacred Mayan text, Popul Vuh. The dancers originally hung from their ankles while playing rattles and other instruments. It is a dangerous dance that has resulted in numerous deaths over its long history (Liner Notes, Palo Volador).

Fig. 8.46: TUBS, Guatemala in North America, 2007. This image depicts North and Central America with the country of Guatemala highlighted in red.

The “Dance of the Conquistadores” is an entertaining dance that serves as a type of social commentary. It developed after the colonial period as a way to make fun of the colonists. Observe how the dancers wear colonial-type costumes and dance in an erratic and ungraceful manner bumping into each other. This dance features the music of the marimba, an instrument that migrated with African slaves to the Americas (Liner Notes, Dance of the Conquistadores).

Closing

This chapter has explored a variety of world music styles, from the songlines of the Australian Aborigines to throat singing in Central Asia. It has covered many new types of instruments and some that evolved into Western instruments, such as the mbira, which is an ancestor of the piano. It is interesting to note that the concepts and use of music are very similar cross-culturally. All over the world, music is used for healing, spiritual understanding, interacting with the universe, and much more. Music is truly universal. It is a medium that transcends language and something all cultures have in common.

Guiding Questions

- What are the similarities and differences found between various types of world music?

- How does indigenous music reflect culture and geography?

- Can you identify Western relatives of instruments found around the world?

- How do the sounds of various world music styles differ from the sounds of Western music?

Self-Check Exercises

Complete the following self-check exercises to verify your mastery of key music terms presented in this chapter. Check your answers at the bottom of the page.

- What is a maqam?

- A dance from India

- A melodic fragment in Arabic music

- A style of music from China

- All of the above

- The gungon is a traditional instrument of what people?

- Australian Aborigines

- Tuvans

- The Dagomba

- The Inuit

- Traditional Chinese music is based upon what type of scale?

- Equal temperament heptatonic

- Just intonation pentatonic

- Major/minor scale

- Mixolydian mode

- Which of the following statements are true of Australian Aboriginal songlines?

- They serve as a repository of cultural knowledge.

- They are maps of specific geographic locations.

- They are the principal medium of exchange.

- All of the above

Self-check quiz answers: 1.b, 2.c. 3.b, 4.d.

Additional Resources

Aboriginal Studies WWW Virtual Library

Agawu, V. Kofi and Kofi Agawu. African Rhythm: A Northern Ewe Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. Print.

al Faruqi, Lois Ibsen. An Annotated Glossary of Arabic Musical Terms. Hartford, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981. Print.

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

Balfour, Mark. “Sacred Sites: Sacred Sounds.” In Song of the Spirit: The World of Sacred Music. New Delhi, India: Varanasi, India: Tibet House, 2000. Print.

“Balinese Dancing in the Period of Modern Society.” ModernSociety.com, n.d. Web. 12 Oct.

2004.

Bebey, Francis. African Music: A People’s Art. Lawrence Hill Books, 1999. Print. Belo, Jane. Trance in Bali. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1960. Print.

Berliner, Paul F. The Soul of Mbira: Music and Traditions of the Shona People of Zimbabwe.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. Print.

Bhattacharya, Dilip. Musical Instruments of Tribal India. New Delhi: Manas Publications, 1999. Print.

Chernoff, John. African Rhythm and African Sensibility: Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981. Print.

Cope, Jonathan. How to Khöömei and Other Overtone Singing Styles. London: Sound for Health, 2004. Print.

Courtney, David R & Courtney Chandrakantha. “Antiquity in Indian Music: Facts Factoids, and Fallacies.” Sruti Ranjani: Essays on Indian Classical Music and Dance, 156-171. The India Music and Dance Society, 2003.

Coutts-Smith, Mark. Children of the Drum. Hong Kong: Lightworks Press, 1997. Print. Cutis, Natalie, ed. The Indians’ Book. Avenel, NJ: Gramercy Books, 1987. Print.

Danielou, Alain. Ragas of North Indian Music. London: Berrie and Rockliff, 1968. Print. Danielson, Virginia. The Voice of Egypt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997. Print.

Diallo, Yaya and Mitchell Hall. The Healing Drum: African Wisdom Teachings. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books, 1989. Print.

Eiseman, Fred & David Pickell, eds. Bali: Sekala & Niskala, Vol. 1. London: Periplus Editions, 1995. Print.

Elkin, A.P. Aboriginal Men of High Degree. Queensland, Australia: University of Queensland Press, 1977. Print.

Elkin, A, P. The Australian Aborigines. 3rd ed. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., 1964.

Print.

Erlmann, Veit. Nightsong: Performance, Power, and Practice in South Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. Print.

Farmer, Henry George. Historical Facts for the Arabian Musical Influence. London: Arno Press, 1978. Print.