7 Chapter 7

Jazz

By Bethanie L. Hansen and David Whitehouse

“But jazz music is about the power of now. There is no script. It’s conversation. The emotion is given to you by musicians as they make split-second decisions to fulfill what they feel the moment requires.” – Wynton Marsalis (Marsalis and Ward 8)

Figure 7.1 Frisco Jass Band, circa 1917.

The Frisco Jass Band was an early U.S. jazz band that recorded for Edison Records in 1917. This publicity shot shows, from left, unknown (drums), Rudy Wiedoeft (clarinet), Marco Woolf (violin), Buster Johnson (trombone), Arnold Johnson (piano), and unknown (banjo).

Jazz is a distinct contribution from the United States to the world’s musical stage. More than a century ago, a confluence of musical styles resulted in a way of playing that came to be known as jazz. The African musical roots of call and response, syncopation, and polyrhythms formed much of the foundation of jazz music, and improvisation gives jazz its energy. It is generally acknowledged that New Orleans was the place where it all began. In this chapter, readers will learn about the beginnings of jazz, noteworthy stylistic developments, and significant songwriters and performers. Given the many styles that have developed within the jazz genre to date, it would be impossible to present a comprehensive discussion in a mere chapter.

Therefore, readers are encouraged to explore the additional resources at the end of this chapter for additional study. For an introduction to jazz before reading the chapter, visit Smithsonian Jazz.

Relevant Historical Events

Known for its distinct cross-cultural and multilingual heritage, New Orleans from the early 1800s on was a destination for a variety of people of different nationalities. The French had established the city, the Spanish ruled for a time, and the Americans known as Kaintucks arrived on flatboats (Shipton 72-73). There were slaves, freemen, and “Creoles of color,” who were the progeny of mixed relationships. New Orleans was home to Choctaw and Natchez American Indians and people from the Balkans including Dalmatians, Serbs, Montenegrins, Greeks, and Albanians. Chinese, Malays, and Spanish-speaking Filipinos were also added to the mix. Among each group, there were additional distinctions. For instance, some of the French were descendants of the original settlers, while others came directly from Canada and France, and still, others were French-speaking former slaves from Haiti and Santo Domingo. Each cultural group brought its own culture and music. This blend of cultures formed the background of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century music born at the mouth of the Mississippi called jazz.

Figure 7.2 George Prince, New Orleans, 1919.

Cultural Influences

Throughout the nineteenth century, several types of music permeated New Orleans. At the northern edge of the city, in a grassy area known as Congo Square, blacks gathered on Sunday to dance to drumbeats and music for several hours. They were slaves engaging in the music and dance of their African ancestors. Theaters hosted minstrel shows where various entertainers performed music and skits comprised of original tunes accompanied by banjo, piano, guitar, or tunes heard on the streets of the city and arranged by the performers. As the performance progressed, each player and singer had a chance to be heard in his or her “take” on the words, melodies, and rhythms in what came to be known as improvisation. This performance style had its roots in the plantations of the region, as workers used music to make the work bearable.

Funeral ensembles, orchestras, and marching bands eventually found their places in New Orleans. Funerals traditionally included a group of musicians accompanying the deceased and gathering mourners on the way to and from the graveyard. On the way to the burial, the musicians played a simple dirge and then a lighter, festive version on the way back home. By the middle of the 1800s, the city was home to two symphony orchestras and three opera houses. Music brought the people of New Orleans together, as people of all races attended and supported the opera houses. Marching bands, too, played a big part in the musical mix of the city.

Figure 7.3 The Mathews Band of Lockport, Louisiana, 1904. Notice which instruments are present.

Listen to “Jazz Me Blues” by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, an example of an early New Orleans band. These bands played music influenced by the styles of European military bands and West African folk music. The Onward Brass Band, Excelsior Brass Band, Olympia Brass Band, and the Tuxedo Brass Band were all well-known groups in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the city. The makeup of the bands varied, but a typical ensemble included at least one cornet, trumpet, trombone, tuba, and snare and bass drums, as shown in Figure 7.3. Other instruments, such as clarinets, violins, guitars, and even stand-up basses, also were included. The designation of “orchestra” and “band” was sometimes interchangeable, always referring to this same instrumentation.

Three different strains of music—ragtime, the blues, and spirituals—were being played at this time in New Orleans that directly influenced the formation of jazz. Ragtime is a style of playing, especially on piano, although entire bands performed in this style too. Ragtime is defined by a steady beat in the pianist’s left hand—or the lower instruments of a band—and syncopation of the melody in the pianist’s right hand—or the higher melody instruments of a band. No matter in which genre a melody was composed, pianists could make a “rag” out of it by playing the melody in a syncopated way against the steady beat of the accompaniment.

Defining Characteristics of Jazz

One of the key traits of jazz music is improvisation, or making up parts of the music as it goes, based on specific rules. In traditional music, a composer wrote down exactly what musicians played, and the musicians did their best to perform precisely by the sheet music provided. In jazz, however, the song is just the beginning, a frame of reference from which musicians can work. Many jazz musicians of the past read music poorly or not at all, but they improvised spontaneously in an energetic, exciting way. Each player in a jazz ensemble showed an elastic, musical mind as he or she “picked up” a tune by ear and followed the progress of a song at the whim of the bandleader. Jazz musicians were capable of making things up as they went along, remaining elastic, ready to do anything spontaneously, and creating new expressions in the true spirit of jazz.

Critical Listening

While listening to samples of different jazz styles throughout recent history, consider improvisation as the most common expressive element in jazz. Many arrangements begin with a main melody or “head” tune followed by a looser section of improvised parts played by one or more soloists and accompanied by the rhythm section. This section then is followed by a repeat of the main melody or “head” tune by the ensemble. After identifying which parts of the music are melodies and which parts are improvisations, one is better able to enjoy listening to jazz and describing the differences between cohesive and spontaneous parts of the music.

Listening Objectives

Your listening objectives during this unit will be to:

- Identify the primary instruments performing.

- Listen to the dynamics and tempo of the music and identify whether it is loud or soft or fast or slow.

- Listen for melody and harmony as well as solo or large-group playing.

Figure 7.4 Clip art image of a man wearing headphones and seated in front of a computer, used with permission from Microsoft.

- Identify any special sounds that may give clues about whether the music is swing (a lot of cymbals), rock (a lot of bass drum), latin (a lot of tom-toms and clicking sounds), or some other form of jazz.

- Identify any sections were a musician or musicians seem to be improvising.

Key Music Terms

Instrumentation describes what kind of instrument or voice produced the music.

Jazz ensembles can be organized into groups of any instrumentation, but there are some standard arrangements. One of the most common groupings today is the standard big

Jazz ensembles can be organized into groups of any instrumentation, but there are some standard arrangements. One of the most common groupings today is the standard big

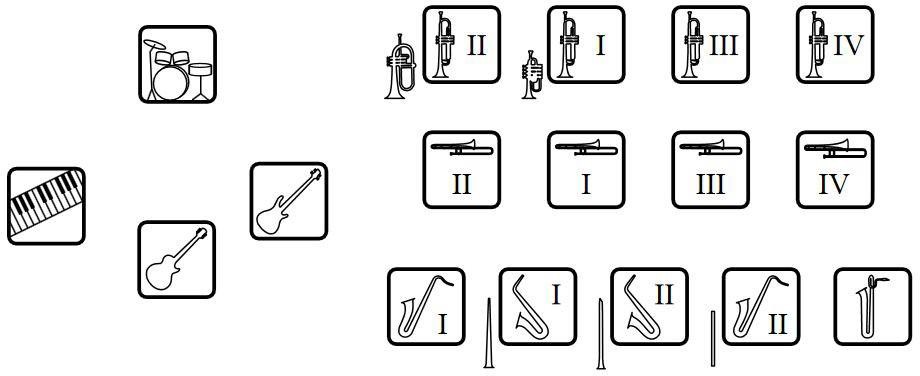

band setup (see Figure 7.5).

Figure 7.5 This diagram shows a typical seating arrangement for members of a modern-day jazz ensemble. On the left, the rhythm section consists of a drum set, keyboard/piano, electric guitar, and bass guitar. On the right are the horns. The trumpets are in the back row, with the first trumpet sometimes doubling on piccolo trumpet or flugel horn and the second trumpet doubling on flugelhorn. In the next row are the trombones, with a bass-trombone playing part IV.

In the front row, the five saxophones include two altos, two tenors, and one baritone. Saxophone players sometimes double on other woodwind instruments, such as the soprano saxophone, flute, or clarinet.

Other instrumentation combinations may be larger, as in the case of a jazz orchestra, or smaller, such as the jazz combo or a bebop ensemble. In each case, there is generally a complete rhythm section supporting other musicians comprised of a drum set, piano or synthesizers, guitar, and bass guitar.

Timbre, or tone quality, describes the quality of a musical sound. Timbre is generally discussed using adjectives, like “bright,” “dark,” “buzzy,” “airy,” “thin,”

Timbre, or tone quality, describes the quality of a musical sound. Timbre is generally discussed using adjectives, like “bright,” “dark,” “buzzy,” “airy,” “thin,”

and “smooth.” Jazz musicians explore a wide variety of timbres, including the wah-wah of a plunger mute on trumpet or trombone, the buzz of a trumpet Harmon mute, the ocean-wave sounds of “brushes” on a drum set, the unique sounds of cymbals of all sizes and thicknesses, and the occasional doubling of saxophone players on flutes, clarinets, or other woodwind instruments. Some jazz musicians can produce growling or flutter-tonguing sounds on wind instruments, and some keyboard players switch to various synthesized sounds for specific genres and styles within jazz. Timbre is a musical element that is often manipulated in jazz music.

Figure 7.6 This image shows a trumpet with mutes commonly used in jazz.

Texture is a term that describes what is going on in the music at any moment.

Texture is a term that describes what is going on in the music at any moment.

Musical texture is the way that melody, harmony, and rhythm combine. The texture in many jazz works is homophonic, with one group playing the melody and other instrument groups playing related chordal accompaniment. In other types of works, such as bebop, more than one melody competes in polyphonic texture. At times, the three brass sections—trumpets, trombones, and saxophones—may all have different competing melodies in polyphony or polyrhythms or both. Additional chordal notes that do not normally occur in the key often enhance textures in jazz music.

Melody is a recognizable line of music that includes different notes, pitches, and rhythms in an organized way. One instrument, an entire section, or the entire

Melody is a recognizable line of music that includes different notes, pitches, and rhythms in an organized way. One instrument, an entire section, or the entire

ensemble in unison may perform the melody in a jazz piece. Sometimes, a band may pass around a melody, with each player playing a small chunk or motif.

Harmony is created when two or more voices perform together. Jazz harmonies are known for being colorful, including dissonant notes or widely spaced intervals, and adding or releasing tension in the music.

Harmony is created when two or more voices perform together. Jazz harmonies are known for being colorful, including dissonant notes or widely spaced intervals, and adding or releasing tension in the music.

When considering musical texture, ask yourself these questions:

- What instruments or voices am I hearing?

- Do I hear one melody or more than one?

- Are the extra voices or instruments changing together or at different times?

- Is it difficult to identify the melody, perhaps because there are several melodies happening at once?

Tempo is the speed of the music. Tempo also may be referred to as “time.” One of the staples in jazz music is syncopation, which shifts the emphasis of rhythms off

Tempo is the speed of the music. Tempo also may be referred to as “time.” One of the staples in jazz music is syncopation, which shifts the emphasis of rhythms off

the beat and creates anticipation or delays. Some jazz works have a “driving” rhythm that moves forward quickly with a strong pulse, and other jazz works seem relaxed in “swing” style, keeping a steady tempo but swinging just a bit behind the beat. Tempo is one factor that helps listeners identify jazz styles.

Dynamics are changing the volume levels of musical sounds. Sudden dynamic changes to louder or softer volumes occur frequently in jazz music and add character to the sound. Brass kicks are a common technique used to change dynamics in jazz. This technique includes sudden loud, punchy notes performed by the bass section against a quieter background, which surprises listeners and adds expression.

Dynamics are changing the volume levels of musical sounds. Sudden dynamic changes to louder or softer volumes occur frequently in jazz music and add character to the sound. Brass kicks are a common technique used to change dynamics in jazz. This technique includes sudden loud, punchy notes performed by the bass section against a quieter background, which surprises listeners and adds expression.

Form is the organization and structure of a musical selection. Many jazz pieces are organized in AABA or ABA form, with the initial melody returning at the end of

Form is the organization and structure of a musical selection. Many jazz pieces are organized in AABA or ABA form, with the initial melody returning at the end of

the work. Improvisation sections may be included.

Composers, Performers, and Listening Examples

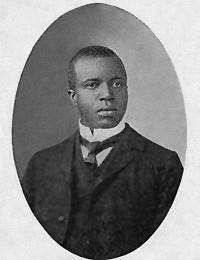

Early Jazz Figure 7.7 Portrait of Scott Joplin, 1907. Joplin is considered the king of ragtime composers.

Figure 7.7 Portrait of Scott Joplin, 1907. Joplin is considered the king of ragtime composers.

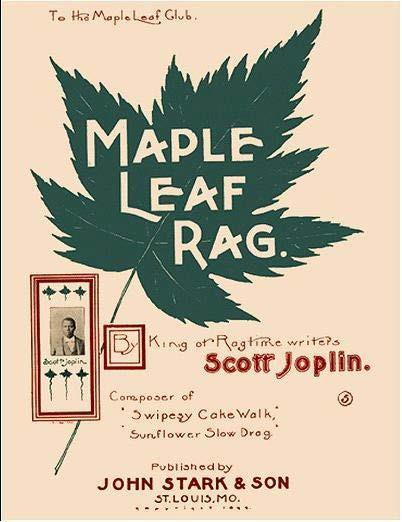

Scott Joplin (1868-1917), considered the king of the ragtime style, influenced countless others in the creation of rags, music characterized by its syncopated melody or ragged rhythm. Born in Texas, he was the son of laborers and learned to sing and play mandolin and guitar in his youth. Joplin eventually learned piano and became an esteemed composer, writing the popular

“Maple Leaf Rag” in 1899. Elements of steady beat and ragged melody were incorporated into this type of jazz. Jazz players were familiar with the style, and when they

added it to blues and orchestrated it, jazz was the result. Joplin struggled financially before his death from disease-related dementia in 1917 at age 49. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize posthumously in 1976 after his work, especially the opera Treemonisha, gained fame (Forney and Machlis 347). His music also was used in the soundtrack to the movie The Sting. Joplin composed forty-four ragtime works, two operas, a musical, a symphony, a piano concerto, and a ragtime ballet, much of which has been lost (Berlin).

Figure 7.8 This image shows the cover of the sheet music for Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag.”

Sippie Wallace, born Beulah Thomas (1898-1986), was a singer and songwriter in the early 1900s blues style. Wallace came from a musical Texas family of thirteen children and moved to New Orleans in 1915 then to Chicago in 1923, deeper into the jazz community. Blues, as a musical genre, originated in communities in the Deep South and entered New Orleans by way of people migrating there from the Mississippi delta. Blues style is defined primarily by the addition of flat tones to a major scale on the third, fifth, and seventh steps. Singers and players can “bend” these notes infinitely, gradually, or greatly so that the music was even more expressive. They used this device to communicate the pain and the woes of life, and Wallace was very effective at communicating these emotions.

Listen as Wallace, one of the most famous jazz singers of the early twentieth century, sings “Devil Dance Blues” (lyrics not necessary for the completion of course) and bends the melody notes masterfully.

The second primary defining element of the blues is its form. It has a twelve-bar form that reflects the words. Listen again to “Devil Dance Blues.” After a short introduction, Wallace sings the first two lines the same then changes the form on the third line. The total of all music for one verse is twelve bars. This pattern (without the introduction) then repeats itself until a short coda-like passage ends the song.

The same twelve-bar pattern applied to strictly instrumental versions of the blues as well. Listen as the Original Dixieland Jazz Band plays “Livery Stable Blues” (1917). After a short introduction, one can discern when the tonal center changes. Listen closely to hear the same twelve-bar pattern as in “Devil Dance Blues,” only at a different pace. Is the tempo in this selection faster or slower than in “Devil Dance Blues”?

Blue notes and twelve-bar form were in the memory and musical ear of every player.

In addition, most players could pick up a tune by ear. To teach the band a new tune, the bandleader might play through the tune first alone, then repeat it several times. As the other players picked up the outlines of the melody, they would join in, and soon the entire band would be playing. Players would take solos with a nod of the head from the leader, shifting back to full sound when the solo verse was over. When ready, the bandleader would signal a return to playing the tune at least once more all the way through with the full band and then bring the piece to a close.

Figure 7.9 Robert Runyon, King & Carter Jazzing Orchestra, Houston, Texas, January 1921. Credit: The Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, image number 05019, courtesy of The Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Louis Armstrong was a well-known jazz trumpet player and singer. Listen as Louis

Armstrong and his Hot Five play the song “Heebie Jeebies.” The song shows some of the basic principles of a jazz band, including a lead instrument (in this case trumpet), an accompanying instrument (clarinet), a basic rhythm section (in this case the piano and the banjo), and a bass instrument (trombone).

Other basic jazz principles are:

- an interplay between the lead instrument and the accompanying instrument(s);

- ragtime technique in the piano, banjo, and trombone, akin to an oom-pah in the bass alternating with chords on the off beats and syncopated melodies on top;

Figure 7.10 William P. Gottlieb, Portrait of Louis Armstrong, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., circa July 1946. Armstrong is a seminal figure in the history of jazz.

- a twelve-bar repeated harmonic structure taken from blues form;

- a lead singer (Armstrong, in this case) with an early example of scat singing;

- varied instrumentation along the way as instruments drop out, play a solo, and rejoin the music for the full band; and

- the ability to improvise, even though on a recording the improvisatory nature of the performance is not as evident as when it is heard live.

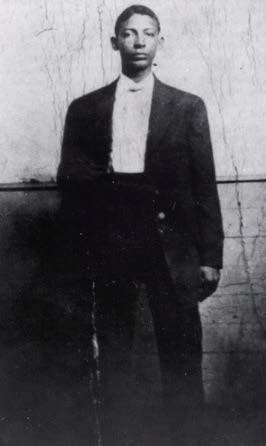

Jelly Roll Morton gave much impetus to the early days of jazz with his solo and group playing and recording, his masterful composing, and his travels. Morton claimed to have single-handedly invented jazz—possibly a tongue-in-cheek claim. Born in New Orleans, Morton was active as a pianist early in life. He engaged in other activities, but piano playing remained his primary profession. He started traveling in 1904 to places including Memphis, Kansas City, and St. Louis, sharing his music along the way. Traveling is one example of how the new jazz style from New Orleans spread not only by Morton but by other solo players and groups as well.

Figure 7.11 Jelly Roll Morton in his teenage years, circa 1906. This image is possibly the earliest photograph of Morton.

New Orleans is situated at the mouth of the Mississippi River. The steamboats that carried people up and down the river also hired musicians to play. These musicians traveled north to faraway places, spreading the new style and sometimes taking up residence in the cities where the steamboats docked. These visiting musicians gave local musicians a chance to assimilate the jazz style and add their own stylistic elements.

Morton eventually made it to Los Angeles, where, due to his popularity, he remained for five years. In 1922, He moved to Chicago to make recordings of others and his own music. Five years after moving to Chicago, he recorded with his band, Jelly

Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers. Morton was able to achieve a maximum synthesis between composed music and improvisation. The solos performed by band members on recordings are remarkable because of the flexibility extended by the bandleader, and colors and textures were paramount in Morton’s mind.

Other important players who influenced the birth and growth of early jazz include Sidney Bechet (clarinet), Joe “King” Oliver (cornet), Buddy Bolden (cornet), Bunk Johnson (trumpet), and Kid Ory (trombone). These names are only a short list of a plethora of singers, players, dancers, church music directors, marching bands, dance bands, riverboat bands, church bands, duos, trios, quartets, quintets, small bands, large bands, and cultural influences of all types that went into the formation of the jazz style.

Additional early jazz resources:

Later Jazz

Between 1935 and 1948, musicians such as Count Basie, Benny Goodman, and Duke Ellington developed swing bands. One of the most exciting purposes of swing music was to inspire dancing. During the years between World War I and World War II, radio shows featured swing music, and it became even more popular (“Jazz”). Swing bands generally used the same seating arrangement (shown in Figure 7.5) as modern-day jazz ensembles.

Listen to the following examples of swing music:

The bebop phase of jazz music taxed the skills of even the best jazz musicians. Just as concert music in the Romantic period required advanced musical skills for most pieces, the bebop period demanded virtuosity. In the 1940s, the cost of traveling with a full swing band became prohibitive, and musicians reacted by creating smaller bebop ensembles (“Bebop”).

These groups consisted of a rhythm section with just a few other musicians, such as one trumpet and/or one saxophone. Improvisation was even more important in bebop, and melodies became less recognizable or familiar and even sometimes unpleasant, reflecting the fear and uncertainty of WWII. Bebop was more challenging to play because of its intricate melodies and fast tempos. New textures were introduced as added notes were included in chords. Bebop in the 1940s paved the way for the modern jazz of today. Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Thelonius Monk, and Dizzy Gillespie are some well-known bebop musicians (Hodeir).

Listen to the following examples of bebop:

As a reaction to the fast tempos and challenging techniques of the bebop trend, a new jazz style emerged in the 1950s called cool school, or West Coast jazz. This style included the same type of small ensembles as bebop, namely the jazz combo, but played music that was more laid back, slower, and melodically pleasing. Cool school music brought back some of the older European concert-music forms, such as the rondo and the waltz, with a focused sound and tone quality. Dave Brubeck and Miles Davis are two musicians from this philosophy.

Listen to the following examples of cool schools:

The next movement in jazz, known as free jazz, lasted roughly thirteen years, from about 1956 to 1969 (“Free Jazz”). The free jazz genre used odd chord progressions, unpredictable forms, awkward structure, and avant-garde moods. The primary purpose of free jazz was to express sounds, not melody or form. This particular type of jazz is more radical than bebop or any other style of jazz music. Listening to this type of jazz takes focused attention and active listening. John Coltrane composed his later works in the free jazz style (Gammond).

Listen to the following example of free jazz:

- An excerpt from John Coltrane’s Ascension

After jazz developed through the swing, bebop, cool school, and free jazz styles, modern performers developed fusion, a style of music based on modes rather than scales and a combination of other techniques from earlier jazz. Using modes meant that a few raised or lowered pitches to fit into a different kind of musical scale altered the set of notes for a given piece. In infusion jazz, musicians often used different and nontraditional combinations of instruments, sometimes including ethnic instruments not normally included in jazz (“Jazz-Rock Fusion”).

Listen to an example of fusion jazz using a few Korean instruments:

Additional later jazz resources:

Closing

Jazz music consists of a mixture of early styles and modern genres. One of the defining features of jazz music is improvisation, or spontaneous music making, at an individual level. There are many styles within the genre of jazz music, including swing, bebop, cool jazz, free jazz, and fusion. In addition to these styles, there are many others, including jazz ballads, funk, and Latin jazz, which have not been discussed in this chapter. As jazz continues to develop in the present era, more techniques and styles may emerge while old ideas are continually reused. Explore jazz music to determine which styles you enjoy, and seek out new and interesting examples. If you wonder whether jazz bands exist and perform today, look no further than your local high school jazz ensemble. If you prefer a more adult ensemble, consider investigating Gordon Goodwin’s Big Phat Band which regularly performs in Los Angeles and on movie soundtracks like Disney’s The Incredibles.

For more information about Gordon Goodwin’s Big Phat Band, visit www.bigphatband.com.

Composers and Improvisers

Guiding Questions:

Identify, describe, and provide examples of jazz music.

- What are some characteristics of early jazz?

- What purposes/subject matters does jazz represent?

- How did jazz styles change during the early twentieth century?

- What are some of the noteworthy pieces that were composed during this period?

- Who are some of the significant jazz composers?

Self-Check Exercises

Complete the following self-check exercises to verify your mastery of key music terms presented in this chapter. Check your answers at the bottom of this page.

- Which of the following phrases could describe early jazz music?

- Based on the African call-and-response pattern

- Influenced by African spirituals

- Began in New Orleans

- All of the above

- Which early style combined a ragged melody with a steady bass part?

- Swing

- Bebop

- Ragtime

- Funk

- What is the most important basic element of jazz music?

- Fast tempos

- Melody played by the saxophone section

- Reading music

- Improvisation

- Which performer both sang and performed jazz on the trumpet?

- Louis Armstrong

- Sippie Wallace

- Jelly Roll Morton

- None of the above

Self-check quiz answers: 1. d, 2. c, 3. d, 4. a

Additional Listening Examples

Swing

“Jeepers Creepers” by Louis Armstrong and Jack Teagarden “How High the Moon,” by Louis Armstrong

Bebop

“Leap Frog” by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie

Theater

“Summertime,” from the opera Porgy and Bess, by George Gershwin

Fusion

“Cantaloupe Island” by Herbie Hancock “Chameleon” by Herbie Hancock

Works Consulted

Armstrong, Louis. “How High the Moon.” 1947. Live in Australia, March 1963. YouTube. 29 Nov. 2009. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://youtu.be/XzOvJ8wYA1I>.

Armstrong, Louis and Jack Teagarden. “Jeepers Creepers.” 1958. YouTube. 24 Nov. 2008.

Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://youtu.be/2jbZrocd6vs>.

Basie, Count. “Swingin’ the Blues.” 1941. YouTube. 15 Oct. 2008. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/TYLbrZAko7E>.

“Bebop.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 27 June 2012.

Berlin, Edward A. A Biography of Scott Joplin. 1998. “Biography.” The Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation, 2004. Web. 5 Sept. 2012.

<http://www.scottjoplin.org/biography.htm>.

Coltrane, John. Ascension. 1965. Perf. New Zealand School of Music. 4 June 2009. YouTube. 23 July 2009. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://youtu.be/-0x1jsVuduU>.

“Composers and Improvisers.” Exploring the World of Music. Prod. Pacific Street Films and the Educational Film Center. 1999. Annenberg Learner. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://www.learner.org/resources/series105.html>.

Construction tools sign, used with permission from Microsoft. “Images.” Office. Web. 4 Sept.

2012. <http://office.microsoft.com/en- us/images/results.aspx?ex=2&qu=tools#ai:MC900432556|mt:0|>.

Ellington, Duke. “Caravan.” 1937. YouTube. 8 Nov. 2010. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/r95flkZciJE>.

—. “Satin Doll.” 1953. YouTube. 30 Oct. 2006. Web. 14 Apr. 2014.

<http://youtu.be/TrytKuC3Z_o>.

“Free Jazz.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 27 June 2012.

Frisco Jazz Band. Circa 1917. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 26 Mar. 2010.

Web. 4 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Friscojazzbandc1917.jpg>.

Forney, Kristine, and Joseph Machlis. The Enjoyment of Music: An Introduction to Perceptive Listening. 11th ed., shorter version. New York: W.W. Norton, 2011. Print.

Gammond, Peter. “Free Jazz.” The Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham. Grove Music Online. Web. 27 June 2012.

Gershwin, George. “Summertime.” Porgy and Bess. 1935. YouTube. 24 Mar. 2009. Web. 1

Sept. 2012. <http://youtu.be/faiG6Ssvpyc>.

Gillespie, Dizzy. “A Night in Tunisia.” 1942. YouTube. 28 Jan. 2008. Web. 14 Apr. 2014.

<http://youtu.be/BQYXn1DP38s>.

Goodman, Benny. “Sing, Sing, Sing.” Hollywood Hotel. 1937. YouTube. 29 Jan. 2006. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://youtu.be/3mJ4dpNal_k>.

Gottlieb, William P. Portrait of Louis Armstrong, Aquarium, New York, N.Y. Circa July 1946. “Performing Arts Encyclopedia.” The Library of Congress. 8 Dec. 2010. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 19 Jan. 2012. Web. 5 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Louis_Armstrong.jpg>.

Hancock, Herbie. “Cantaloupe Island.” 1964. YouTube. 1 Aug. 2006. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/XrgP1u5YWEg>.

—. “Chameleon.” 1973. YouTube. 12 Aug. 2011. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/onbKsXUnI4c>.

Hodeir, André. “Bop.” Oxford Music Online. Grove Music Online. Web. 27 June 2012 “Jazz.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc.,

2012. Web. 27 June 2012.

“Jazz-Rock Fusion.” The Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham. Grove Music Online.

Web. 27 June 2012.

Jelly Roll Morton in his Teenage Years. Circa 1906. “Oh, Mister Jelly”: A Jelly Roll Morton Scrapbook. Copenhagen: Jazz Media, 1999. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 4 Aug. 2012. Web. 5 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:TeenagedJellyRollMorton.jpg>.

Joplin, Scott. “Maple Leaf Rag.” 1899. Cond. Zachary Brewster-Geisz. Perf. Garritan Personal Orchestra’s sample library. 1 June 2006. “Community Audio.” Internet Archive. 10 Mar. 2011. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://archive.org/details/MapleLeafRag>.

Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five. “Heebie Jeebies.” 1926. YouTube. 6 Jan. 2009. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://youtu.be/ksmGt2U-xTE>.

Mako098765. Trumpet Mutes. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 23 August 2006. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:TrumpetMutes.jpg>.

Man working at the computer and listening to headphones, used with permission from Microsoft. “Images.” Office. Web. 4 Sept. 2012. <http://office.microsoft.com/en- us/images/results.aspx?qu=listening%20to%20headphones&ctt=1#ai:MP9004225 41|mt:2|>.

Maple Leaf Rag. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. 19 Apr. 2009. Web. 5 Sept. 2012.

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Maple_Leaf_Rag.PNG>.

Marsalis, Wynton, and Geoffrey Ward. Moving to Higher Ground: How Jazz Can Change Your Life. New York: Random House, 2008. Print.

Monk, Thelonius. “Straight, No Chaser.” 1951. Perf. Thelonius Monk Quartet. Monk in Tokyo.

1963. YouTube. 28 June 2013. Web. 22 Dec. 2014.

<http://youtu.be/uxdnQOs0BNo>.

Oriental Express. “Monsoon.” 2007. Korean Traditional Instrument and Fusion Jazz Concert, Seoul, South Korea, 2007. YouTube. 27 June. 2008. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/oXtrD9Oz2eE>.

Original Dixieland Jazz Band. “Jazz Me Blues.” 1921. “National Jukebox.” Library of Congress. Web. 14 Apr. 2014.

<http://www.loc.gov/jukebox/recordings/detail/id/7835/>.

—.. “Livery Stable Blues.” 1917. “National Jukebox.” Library of Congress. Web. 14 Apr.

2014. <http://www.loc.gov/jukebox/recordings/detail/id/4668/>.

Parker, Charlie. Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins, Ella Fitzgerald, Hank Jones (1950). YouTube. 7 March 2015. Web. 19 April 2019.

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mwT9iHBWTVI>

–. Sessions – Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins, Ella Fitzgerald, Hank Jones

The Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 19 Dec. 2011. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scott_Joplin_19072.jpg>.

Prince, George. New Orleans, 1919. 17 Nov. 1919. “American Memory.” The Library of Congress. Web. 4 Sept. 2012. <http://memory.loc.gov/cgi- bin/query/D?pan:9:./temp/~ammem>.

Portrait of Scott Joplin. American Musician. 17 June 1907. Performing Arts Reading Room, The Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 19 Dec. 2011. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scott_Joplin_19072.jpg>.

Runyon, Robert. King & Carter Jazzing Orchestra, Houston, Texas, January 1921. Robert Runyon Photograph Collection. The Center for American History and General Libraries, the University of Texas at Austin. “The South Texas Border, 1900-1920.” The Library of Congress, 30 Aug. 2012. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.award/txuruny.05019>.

Shipton, Alyn. A New History of Jazz. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2001. Print.

Smithsonian Jazz. The National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. Web.

20 June 2016. <http://americanhistory.si.edu/smithsonian-jazz>.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet. “Take Five.” Time Out. 1959. Jazz Casual. 1961. YouTube. 15 Feb. 2008. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://youtu.be/PQLMFNC2Awo>.

The Mathews Band of Lockport, Louisiana. 1904. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 1 Jan. 2010. Web. 4 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MathewssBandLockport.jpg>.

The Miles Davis Quintet. “It Never Entered My Mind.” Workin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet.

1956. YouTube. 12 Jan. 2014. Web. 19 April 2019.< https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=- Np8PJDGq_A>

Wallace, Sippie. – Devil Dance Blues. YouTube. 10 Aug. 2013. Web. 19 April 2019.

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wRASFx-klto>

Wilson, Matthew D. Diagram showing a typical seating arrangement for members of a jazz ensemble. 26 Nov. 2008. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 27 Nov.

2008. Web. 15 May 2012. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Jazz_ensemble_-

_seating_diagram.svg>.

Young, Lester. “Mean to Me.” N.d. Art Ford’s Jazz Party. Danmarks Radio. 25 Sept. 1958.

YouTube. 20 July 2010. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://youtu.be/9wvAjA-ovhs>.