6 Chapter 6

Twentieth-Century Music

By Bethanie L. Hansen

“A song has a few rights, the same as other ordinary

citizens If it happens to feel like trying to fly where humans

cannot fly, to scale mountains that are not, who shall stop it?” – Charles Ives (1874-1954)

Figure 6.1 Ray Man, Portraitfoto von Arnold Schonberg, 1927.

20th Cent. Introduction video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ttt0Ef7_9_8

History Content – Beg-2:50mm, Intro Composers – 2:51-3:42mm, Primitivisum – 5:04-8:18mm, Conclusion – 8:19-End.

As the nineteenth century ended, common musical rules were questioned, bent, reinvented, altered, and sometimes thrown away completely. Beginning in the Romantic era, music began to diverge into many genres and styles. It would be difficult to present music of the twentieth century (1910 to present) clearly as a unified style because many new and unusual trends developed and continue to develop today.

Composers both returned to tradition and moved farther from it during the twentieth century. This chapter will give a brief overview of artistic developments that led to significant twentieth-century styles, the historical context of the twentieth century, and detailed introductions to specific schools of thought and genres of the modern age.

The term twentieth-century music generally refers to formal concert music of the 1900s, rather than rock, pop, jazz, or world music (Burkholder). A line seems to be drawn between these two basic genres, and that’s where we get the general term of “CLASSICAL” music vs. “POP” music in the 20th Century. What’s interesting, is the term, “long hair music”. Technically, long hair music is referred to as the earlier composers like Bach, Mozart, & Beethoven, because they had long hair. When long hair was popular with rock & roll artists of the late 1960’s, 70’s & 80’s, their music was referred to as “long hair music”, and it became a bit of a conflict of interest.

Twentieth-century composers embraced the term, “Modern Concert” or (“Classical”), to name their musical era because it seemed modern and exciting and the various styles of music could not be combined together under one stylistically descriptive term. Twentieth-century music was preceded by several late Romantic era developments, including impressionism and neoclassicism. In the 1900s, expressionism, serialism, modernism, electronic music, minimalism, experimental music, and chance music emerged and became intellectually based musical styles. While the music was distinguished by form and instrumentation in the Classical period and by composer and nationality in the Romantic period, music of the twentieth century seems to fit into trends and movements tied closely to visual arts.

Relevant Historical Events

History Content – Beg-2:50mm – 20th Cent Introduction video

By the early 1900s, the Western world had experienced the second industrial revolution and welcomed the age of the automobile. A major earthquake hit San Francisco early in the century, devastating residents and destroying their property. The aviation industry was developed by creative and courageous pioneers who conducted early flights and combined the internal combustion engine with the winged glider to produce an airplane. Just as a general feeling of prosperity settled on people of the twentieth century, the luxurious cruise ship Titanic sank and World War I began.

Figure 6.2 Wright Aeroplane, 1908.

Political Influences

The early twentieth century brought wars and major political changes throughout the world. World War I (1914-18) involved what was commonly referred to as the great powers. This term refers to major nations that participated in the war and sat on either the Allies’ side or the Central Powers’ side. This war involved more than seventy million servicemen and women, more than nine million of whom died. The impact of World War I was widespread and led to political changes in various nations, including the former German, Ottoman, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian empires—all of which dissolved. A second major war followed only twenty-one years after the first one ended. World War II (1939-45) was a global war even larger in scope and significance than the first. More than one hundred million people served in militaries throughout the war. This time, though, countries joined either the Allies or the Axis side. Both military and civilian deaths occurred, including many casualties from the atomic bomb explosion and the Holocaust. It has been estimated that between thirty-five and sixty million people died in World War II (“World War II”).

Social Influences

The women’s suffrage movement began in the 1800s. It was first formalized in 1848 at the convention in Seneca Falls, New York. This movement aimed to reform voting rights to allow women to vote and run for political offices. Women gained the right to vote in 1920 after WWI had ended.

Figure 6.3 Rose Sanderson, Bain News Service, 1913. Women suffragists demonstrate in February 1913. The triangular pennants read “Votes for Women.”

During the 1920s, Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) began to compose neoclassical works that involved composing techniques from the Classical period (beginning with the ballet Pulcinella), and Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) shifted from writing a massive opera to creating twelve-tone serialism. Both of these composers are presented later in this chapter.

A few years later, between WWI and WWII, countries throughout the world experienced economic hardship as they entered a period known as the Great Depression. In the United States, unemployment soared and stock prices declined by 89 percent. Between 1929 and 1954, stock prices were volatile, and unemployment hit 24.9 percent at one point (Taylor). Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated as president in 1933 and resolved to help the nation regain its strength and stability. The president introduced his New Deal, which reformed banking, stabilized agricultural production, created public works programs, built dams and power plants, and brought relief to the downhearted (Beschloss and Sidey). President Roosevelt presented encouraging fireside chats over the radio to hearten Americans. The Depression was difficult for people to endure, and after having been at war for several years during WWI, society struggled to feel hopeful.

Cultural Influences

Edison Phonograph 1878 tin foil recording/playback (movie clip) (3:45mm)

Wax Cylinder Recording/Edison record/playback Phonograph (1903) (1:35mm)

Recorded sound was developed in the late nineteenth century, and movies and television were invented during the 1900s. The first films with sound were music-only presentations called “Silent Movies”. Eventually, voices, music, and sound effects were combined and used to present films, such as The Jazz Singer for Warner Brothers in 1927, called “talkies” (“Motion Picture”). Paris and the rest of Europe were behind the United States in developing this revolutionary and impressive art. The Jazz Singer was shown in London in 1928, and before long studios in both Europe and the United States had moved to using recorded sound in films. The first feature-length European talkie was the British film Blackmail (1929), directed by Alfred Hitchcock (Thompson and Bordwell 3-4).

The development of recorded sound and video affected music production in the 1900s in two ways. First, musical works became available to an even wider audience, as early films used Western concert music as accompaniment. Second, an unfortunate negative effect was that musicians who used to sing and play instruments in communities for enjoyment began to compare themselves to trained instrumental and vocal stars, and over time, the general population produced fewer and fewer musicians.

Defining Characteristics of Modernism in Music

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, certain composers wrote pieces that left the realm of tonality and entered the world of abstract musical sounds. Claude Debussy paved the way for unique approaches to tonality by writing impressionist music, where the key or tonal center was de-emphasized or hidden. He worked with new scales, like the whole-tone scale. In 1913, Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring changed performance music dramatically with its aggressive music. Some composers’ works were called neoclassical because they clung to older tonalities and rules of composing and created music inspired by the Classical period with a modern flair. More remote and innovative composers, such as John Adams, György Ligeti, John Cage, and others, created experimental, chance, and minimalist works.

Specific Modern Genres

“Modernism” is a term used to describe a period of change and progress. As a musical term, modernism describes the period beginning in the late nineteenth century when new techniques, sounds, and forms were created. Stravinsky’s music can be described as modernist, as can Schoenberg’s. Some musical styles within the modernist movement were impressionism, serialism, minimalism, electronic music, experimental music, and chance music. Composers from this period who created innovative and nontraditional works were called avant-garde, meaning they radically departed from the traditional methods of composing and performing music (Samson). Notable avant-garde composers, other than Schoenberg and Stravinsky, were Anton Webern, Charles Ives, John Cage, Milton Babbitt, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and György Ligeti. Listen to Ligeti’s piece “Artikulation.” (a must listen and watch video)

French Impressionism

(As we covered in the Romantic Era, as a link between the Romantic Era and Modern 20th Century Era.)

Impressionism originated in France as a reaction against the emotional music of the Romantic era. During the late Romantic period, impressionism produced the work of French composer Claude Debussy (“Impressionism”), whose work consisted of special whole-tone and pentatonic scales. The goal of impressionist music was to produce a mood or sense of

something without boldly presenting it. Impressionist music is delicate, sensuous, and calm. In visual arts, the impressionist movement included such well-known artists as Edgar

Degas, Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Painters converged on Paris as the place to develop impressionist art focusing on light and movement. To learn more about impressionist art, visit the Musée d’Orsay website.

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) was the primary composer of impressionism. He worked to communicate images, feelings, and moods through his music rather than by

portraying literal descriptions common to program music. Debussy can be considered the bridge between the Romantic period and the twentieth century, similar to Beethoven being considered the transitional composer between the Classical and Romantic periods. Some of Debussy’s popular piano and orchestral works include Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun (1894), Nocturnes (1899), La Mer (1905), and “Claire de Lune” (1905) a simple melody included in any concert band method book on the market today. Debussy’s impressionist compositions were instrumental works for both piano and orchestra.

The rich texture of Debussy’s music is lush and sensual. The tonality is vague and difficult to pin down, as there is no clear tonal center. The basis of a whole-tone scale is that all notes are equally separated, and there are no patterns of whole and half steps. Instead, all pitches in a whole-tone scale are a whole step apart. Using this and other new scales, Debussy invented unusual harmonies in his music that kept listeners on edge as they waited for the music to settle somewhere.

To learn more about impressionism in music, watch Yale University’s Open Yale Courses lecture “Musical Impressionism and Exoticism: Debussy, Ravel and Monet,” presented by Professor Craig Wright. Viewing this lecture content is not required in the APUS MUSI200 Music Appreciation course and is

Figure 6.4 Edgar Degas, Ballet Rehearsal on Stage. 1874.

Expressionism

Pioneered by Schoenberg and his students Anton Webern and Alban Berg, expressionism was a style of atonal music that later led to the development of serialism. Together Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg were known as the Second Viennese School (1903-25) because they developed revolutionary musical ideas in Vienna—the same city where Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven (the First Viennese School) composed and performed during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Schoenberg was a traditional and conservative music composition teacher, but his spirit of ingenuity and creativity drove the expressionist movement.

One of Schoenberg’s first expressionist works was the Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 16 (1909), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3bqlt1EOlwg , which was written in an attempt to avoid any kind of structure or form. This goal was a direct rebellion against the structure and form valued in the Classical and Romantic periods. Schoenberg was influenced by the philosophies of the subconscious mind published by Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). As a result Schoenberg attempted to create music that flowed freely of its own will, like subconscious thought (Carpenter). While this method of composing was interesting, it was difficult to regulate and eventually led to the creation of serialism, which, in contrast, was ruled by strict order, form, and method. For a detailed explanation of atonalism and the twelve-tone row system, watch “Atonal Music Explained in a Nutshell” (transcript available).

Serialism

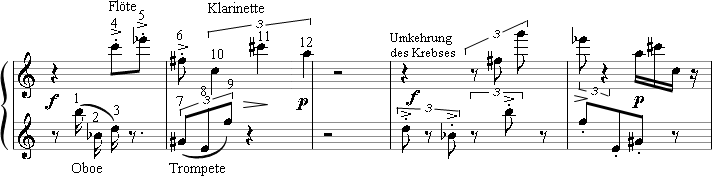

Serialism naturally developed out of the expressionist music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, though Schoenberg himself is credited with having created it. The twelve notes of an octave are used in whatever order the composer decides (all of the black and white keys of the piano between one note and its same-named note above or below it) (Whittall). The first twelve-note set is called the “prime.” The prime set can be played backward, upside down, and upside down and backward (see illustration, below). Then, the note sets can be chunked into smaller motifs, paired with other notes and rhythms, passed from one instrument to another in an ensemble, and repeated, unless the composer using serialism is a purist. Then, the entire twelve-note phrase must be played out before a new one can be started. In addition to its own stylistic rules, serialism was further supported through harmony and music concepts from earlier periods. To see serialism explained visually, watch the video “12 Tone Serialism” on YouTube. For a detailed explanation of atonalism and the twelve-tone row system, watch “Atonal Music Explained in a Nutshell” (transcript available).

Figure 6.5 Image courtesy of Hyacinth at en.Wikipedia, “Prime, retrograde, (bottom-left) inverse, and retrograde-inverse,” 2011. This image shows an example of the twelve notes used in serialism. P signifies “prime,” or the original melody; R signifies “retrograde,” or the original melody played exactly backward; I signifies “inversion,” or the original melody flipped upside down; RI signifies “retrograde inversion,” or the original melody flipped upside down and backward.

Figure 6.6 Arnold Schoenberg, “Bar 1-5 from Schönbergs Opus 24, 1.” 1920-23. This image illustrates twelve-tone writing.

Serialism was not a style for instrumental music alone; many vocal and orchestral pieces also were composed in this style. One Schoenberg piece, Pierrot Lunaire, includes a combination of dramatic singing and speechlike sounds called Sprechstimme. Listen to Schoenberg discuss his art during an interview. All elements of a piece, including the dynamics, could be serialized. The dynamics would then cycle through changes in a controlled manner. Listen to “Nacht”(night music), from Pierrot Lunaire and try to identify a melody or pieces of a melody. Finding a melody will be a nearly impossible task, as twelve-tone music is calculated and not composed with the idea of a recognizable melody. Furthermore, Schoenberg in particular seems to have aimed for wide melodic leaps, serialized rhythms as well as notes, and even timbres organized in a serial pattern. Some people struggle to find the musical value in serialism because it seems to lack emotion or the coherent repetition that draws listeners in. With an understanding of what it is and how it is made, anyone can learn to understand and appreciate serialism.

Figure 6.7 Stravinsky Bain News Service

Schoenberg’s publisher, Belmont Music Publishers, offers several videos that chronicle his life and music. One of these videos presents a discussion of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone serialism, including when and how he developed it and what it sounds like. For additional insight regarding serialism, watch “Arnold Schoenberg and Twelve-Tone Music.”

Neoclassicism

Not all composers wanted to explore new musical territories in the same ways. Several preferred to abide by traditional composing rules and norms while experimenting with ideas inside those rules. This style was called neoclassicism (Walsh). To help traditionally composed music sound more relevant for modern times, composers introduced devices or tools, such as chromaticism and polytonality, into their works. Igor Stravinsky was one such composer. He entered the musical scene with experimental and controversial music but later wrote in a neoclassical style.

Stravinsky was born in Russia and later moved to Switzerland, France, and eventually to the United States. He is known for his ballets Firebird (1910), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIR7iv8DVW8 Petrushka (1911), and The Rite of Spring (1913). These works expressed bold, dissonant sounds that at first repelled listeners. The Rite of Spring incited a riot at its first performance in Paris because of the

primal nature of the ballet choreography involved. The dancing portrayed violence, a mating scene, and the wildness of nature. Stravinsky’s music was remarkably different from other music of the Romantic period, although it was similar to extremes often portrayed by other composers of his era. His music was edgy, intense, and bold. As you listen to an excerpt from The Rite of Spring, notice the dissonant harmony and changing, asymmetrical rhythms and meters. The timing will seem inconsistent; look for patterns and change.

Figure 6.8 Andrea Balducci, Le Sacre Du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) performance, August 23, 2009.

Neoclassicism was a movement to return to traditional musical practices. This return doesn’t mean the resulting music sounds like a Classical period selection, but the basic forms and structure of earlier periods are used. Stravinsky’s more conservative neoclassical pieces include TheSoldier’sTale(1918), Oedipus Rex (1927), Symphony of Psalms (1930), and The Rake’s Progress (1951). He contributed to the larger musical world by deeply exploring rhythmic expression, and irregular meters, and placing emphasis (or accents) in unexpected places to upset audience predictions and keep his works spontaneous.

Stravinsky continued the work of extending instrument ranges to extremely high- and low-pitch possibilities that had been explored by several Romantic composers before his time. He also creatively used musical forms and tools employed by Romantic composers.

To learn more about modernism in Stravinsky’s music, watch Yale University’s Open Yale Courses lecture “Modernism and Mahler” presented by Professor Craig Wright. This presentation includes a discussion of Stravinsky’s innovative rhythms, Schoenberg, and other modernist composers. Viewing this lecture content is not required in the APUS MUSI200 Music Appreciation course and is for additional information only.

Gustav Holst – Neo-classicism

The Planets was composed over nearly three years, between 1914 and 1917.[1] The work had its origins in March and April 1913, when Gustav Holst and his friend and benefactor Balfour Gardiner holidayed in Spain with the composer Arnold Bax and his brother, the author Clifford Bax. A discussion about astrology piqued Holst’s interest in the subject. Clifford Bax later commented that Holst became “a remarkably skilled interpreter of horoscopes”.[2] Shortly after the holiday Holst wrote to a friend: “I only study things that suggest music to me. That’s why I worried at Sanskrit.[n 1] Then recently the character of each planet suggested lots to me, and I have been studying astrology fairly closely”.[4] He told Clifford Bax in 1926 that The Planets: Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3OD_HzdZwKk

20th Cent. Introduction video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ttt0Ef7_9_8

History Content – Beg-2:50mm, Intro Composers – 2:51-3:42mm, Primitivisum – 5:04-8:18mm, Conclusion – 8:19-End.

Post Modern “Classical” Music: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KGFYjlL2tCg

Electronic Music

The development of recording technology allowed composers to use the recording process as a new musical form. In the 1950s, musicians in Paris experimented with using magnetic tape to manipulate sounds, calling the medium musique concrète. This term was first used by composer Pierre Schaeffer in 1948. Edgard Varèse (1883-1965) was one composer widely known for exploring this style. He was born in Paris and studied music both there and in Berlin in the early 1900s. His early works were burned in a 1918 fire, shortly after which he moved to New York. Varèse formed the International Composers guild in 1921 and began composing electronic compositions in 1953. His early music interests indicate that he attempted to produce works requiring recorded sound long before the technology was available. Many people followed Varèse’s music throughout his life, including Frank Zappa, who is said to have first listened to a record of Varèse’s music at age fifteen. Edgard Varèse radio is available online with streaming samples of his work, including a sample of the innovative Poéme Électronique.

Other electronic developments in music included the invention of the synthesizer and Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI). Music and instrumental sounds could be created using a computer, allowing composers to control every part of a musical piece by programming the note lengths, dynamics, pitches, and other features into the equipment.

Melody, harmony, and texture, as have been presented in this course, do not occur in most electronic compositions the same way they have in music of past centuries. Instead, the tones and sounds are treated as elements to be manipulated and serve as the building blocks of electronic composition. Pierre Boulez, Arthur Honegger, Lejaren Hiller, and Karlheinz Stockhausen are some noteworthy composers of electronic music.

Karlheinz Stockhausen (German: [kaʁlˈhaɪnts ˈʃtɔkhaʊzn̩] (![]() listen); 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important[1][2][3][4] but also controversial[5] composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groundbreaking work in electronic music, for introducing controlled chance (aleatory techniques) into serial composition, and for musical spatialization.

listen); 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important[1][2][3][4] but also controversial[5] composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groundbreaking work in electronic music, for introducing controlled chance (aleatory techniques) into serial composition, and for musical spatialization.

Stockhausen’s “Kontakte” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l_UHaulsw3M

Chance Music

John Cage (1912-92) challenged the notion that music must be created with tonal sounds. Cage espoused the idea that non-musical sounds, chance noises, and other sounds could be considered music, too. He published many works based on the idea of chance music and prepared instruments. Cage presented a prepared piano work called The Seasons in 1947. His Indeterminacy: New Aspect of Form in Instrumental andElectronic Music (1959) combined instrumental and vocal sounds with electronic material. The Rozart Mix (1965) presents the unique sounds of piano combined with cassette tape recorders.

Cage is most widely known for his unusual piece 4’33”, where the performer prepares the

instrument but sits silently for four minutes and thirty-three seconds, while the audience and ambient noises are considered the real “music” of the performance event.

Figure 6.9 David Tudor and John Cage at Shiraz Art Festival, 1971. Courtesy of the Cunningham Dance Foundation Archive.

Learn more about John Cage at his official website, which features a discussion of his life through his autobiographical statement and a few artifacts from his composed works.

Key Differences between the Romantic Period and Modernism

The Romantic period was a time of breaking the mold, and the twentieth century has been a time of innovation. In the Romantic era, composers branched out, invented their own forms if needed, and focused on emotion and expression over restraint. Although Romantic composers tried smaller and larger forms, some chromaticism, and more complex textures, the modern period has unleashed a wealth of new scales, ideas, and approaches.

The whole-tone scale and other new scales are widely used, and serialism has been developed to systematically involve all twelve notes in an octave. Debussy, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg were pivotal figures who created innovative ways to approach tonality, rhythm, meter, and harmony. Avant-garde composers like Varèse and Cage used instruments and electronics in new ways, developing electronic, minimalist, and chance music and pushing the idea of “serious” music further from the mainstream. Modern composers today, such as Steve Reich, continue these developments.

Critical Listening

While listening to music from the twentieth century, notice the variety of differences from earlier music eras. Focus on listening to identify the specific instruments and sounds produced, and try to describe them. In the case of music from the later 1900s, traditional instruments may have been used in unusual ways to produce sounds that are often unidentifiable, such as a prepared piano that sounds like clicking noises. After listening for instrumentation, notice the volume of the music. Is it loud, soft, or changing? Dynamics vary and may be either static or constantly changing in twentieth-century music. Finally, listen for any harmony that may be present. Are there melodies? Do they have support in other instruments or voices? Do the sounds you hear work together in a pleasing way, or is there a lot of dissonances that sounds grating or chaotic? Some impressionist music includes dissonance, but it is especially common during the modernist period. Use these music analysis skills to explore the assigned listening selections.

Listening Objectives

Listening objectives during this unit are:

- Listen for instrumentation and timbres, including voices or instruments that are performing.

- Listen for dynamic and tempo changes, including sudden loud or soft passages and sudden faster or slower sections.

- Note any harmony or dissonance that may be present.

- Practice describing these concepts using the music terms instrumentation, timbre, texture, tempo, dynamics, and form.

Key Music Terms

Instrumentation describes what kind of instrument or voice produced the music. In  the twentieth century, voices were used a lot like nonvocal instruments.

the twentieth century, voices were used a lot like nonvocal instruments.

Sometimes voices were expected to produce sound effects, nontextual noise, and wide leaps as in an expressionist or serial work. Later twentieth-century music used traditional instruments in unusual ways, as in the case of the prepared piano employed by composer John Cage.

Timbre or tone quality was explored in depth during the twentieth century. Although Romantic-period composers explored a variety of timbres, twentieth-century composers pushed the limits much further. Instruments were used to produce unusual timbres in experimental music and modern works.

Timbre or tone quality was explored in depth during the twentieth century. Although Romantic-period composers explored a variety of timbres, twentieth-century composers pushed the limits much further. Instruments were used to produce unusual timbres in experimental music and modern works.

Texture is a term that describes what is going on in the music at any moment. In earlier periods, texture included a discussion about melody, harmony, and rhythms. In the twentieth century, the texture was no longer the emphasis of composition but can be discussed conceptually. For example, Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire is based on serialism, so a clear melody doesn’t line up with other musical factors as a particular texture like homophony or polyphony. Instead, one must discuss the twelve-tone row and its role in the overall work.

Texture is a term that describes what is going on in the music at any moment. In earlier periods, texture included a discussion about melody, harmony, and rhythms. In the twentieth century, the texture was no longer the emphasis of composition but can be discussed conceptually. For example, Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire is based on serialism, so a clear melody doesn’t line up with other musical factors as a particular texture like homophony or polyphony. Instead, one must discuss the twelve-tone row and its role in the overall work.

Tempo is the speed of the music. Tempo may also be called time. During the twentieth century, composers varied in their use of changing tempos. Stravinsky generally wrote for a fairly regular tempo. In his middle period, however, Schoenberg focused on free-form, non-metered improvisational music called free atonal expressionism.

Tempo is the speed of the music. Tempo may also be called time. During the twentieth century, composers varied in their use of changing tempos. Stravinsky generally wrote for a fairly regular tempo. In his middle period, however, Schoenberg focused on free-form, non-metered improvisational music called free atonal expressionism.

Dynamics are the volume levels of musical sounds. Changing dynamics were used in previous musical eras to communicate emotion or expression. In the twentieth

Dynamics are the volume levels of musical sounds. Changing dynamics were used in previous musical eras to communicate emotion or expression. In the twentieth

century, dynamics were used as another manipulative tool, similar to changing a rhythm or a pitch. Dynamics were also used to give the music expression, make it interesting, and add variety.

Form is the organization and structure of a musical selection. Some twentieth-century composers favored the neoclassical trend of using forms from previous eras: the sonata, the rondo, and other common forms.

Form is the organization and structure of a musical selection. Some twentieth-century composers favored the neoclassical trend of using forms from previous eras: the sonata, the rondo, and other common forms.

Experimental and modernist composers favored using no form at all. Sometimes, ideas were through-composed and never repeated.

Composers

Several of the important composers of the twentieth century, Debussy, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Varèse, and Cage, have been introduced earlier in this chapter. There were

many other great composers throughout the twentieth century, such as Randy Hostetler, minimalist composer Terry Riley, Aaron Copland, and George Gershwin. Please explore the additional listening links at the end of this chapter to learn more.

Discussion: How do music concepts from Western concert music apply to popular music?

Listening to popular music and discussing it with music terminology is a great way to continue developing music appreciation skills. Popular music is generally less complex than Western concert music from most periods, and listeners are more likely to think about music with which they are already familiar. Just like Western concert music was shaped by surrounding political, social, and cultural events, popular music is influenced by many factors. Pop music is shaped by its own history; earlier songwriters, musicians, and artists helped shape what is heard on the radio today. Listen to music on CDs, MP3s, the radio, or over the internet using the skills gained throughout this course. Hopefully, your new music term vocabulary will continue to be a part of your thoughts about music.

Listeners notice that many of their favorite popular songs have a form like those of the Classical or Baroque periods. Many songs follow a verse-chorus pattern that can be analyzed as A A B A B, where A is the verse, and B is the chorus. Listeners can predict that the next section is coming because the background harmonies change, a cadence occurs that plays a defining chord at the end of the section, and the music transitions to the next section.

Closing

The twentieth century included a vast array of music in individualized and often intellectual styles. Some of these styles include expressionism, serialism, modernism,

electronic music, minimalism, experimental music, and chance music. Many composers from this era are still living and composing, and their music continues to develop. While only a few examples were presented in this chapter, there are many more available that listeners are encouraged to discover. Popular music of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries was not presented in this chapter, but students are encouraged to apply their listening skills to their favorite tunes. Doing so can help encourage the growth of music analysis skills and abilities.

Music and Technology

Guiding Questions

Identify, describe, and provide examples of various types of music from the twentieth century.

- What are some characteristics of twentieth-century music?

- What purposes/subject matters are represented in twentieth-century music?

- How did forms change during the early twentieth century?

Self-Check Exercises

Complete the following self-check exercises to verify your mastery of key music terms presented in this chapter. Check your answers at the bottom of the page.

- Which late Romantic period music style involved special scales (such as the whole- tone scale) and lush harmonies?

- Electronic music

- Musique concrète

- Chance music

- Impressionist music

- Which composer was responsible for inventing a completely new system of composing music based on twelve pitches?

- Edgard Varèse

- Arnold Schoenberg

- Claude Debussy

- Igor Stravinsky

- Who considered all kinds of sounds to be music and composed a three-movement piece called 4’33” based on silence?

- John Cage

- Edgard Varèse

- Claude Debussy

- Maurice Ravel

- Which of the following traits effectively describes modernist music?

- Innovative

- Predictable

- Orderly

- Repetitive

Self-check quiz answers: 1. d. 2. b. 3. a. 4. a.

Additional Resources

Visit the following resources to learn more about twentieth-century music:

ErikSatiemusiconlinePBS.org:JohnCage

TheCharlesIvesSocietyMortonFeldman

IgorStravinskymusiconlineKarlheinzStockhausen

Transcript: “Atonal Music Explained in a Nutshell”

Atonality is the systematic avoidance of permitting any single pitch to sound as a tonal center–the system of going beyond tonality as a basis for musical thought construction. It is the organization of sound without key establishment. Atonality is said to operate within a syntax that favors dissonant formations, and its organization is based upon shifting intervallic tension or order of tones.

The various elements in atonal music are tightly knit, usually, by extreme motivic concentration; and reference is constantly made to previous material. And, in many cases in atonality music, especially strict composers, there’s little regular rhythmic stamping and no continuous chain rhythms. The rhythmic patterns are usually asymmetrical, and the meter is irregular and often complicated. Of course, there are many variations you can do with atonal music. Within your tone row, if you want to add a major third or a minor third, or you get stuck with that in composing your tone row, then you can “go with it.” You can go from one extreme to the other; there’re so many different variations within that spectrum between atonality and tonality.

The twelve-tone technique, or composition with twelve notes related to one another, is designed to methodically equalize all pitches of the chromatic scale by the following means:

- A twelve-tone composition is to be based on an arrangement, or series, of the twelve pitches that are determined by the composer. This arrangement is the “tone row,” or “set.”

- No pitch may be repeated until all other pitches have been sounded. There is one exception to this restriction. A pitch may be repeated immediately after it is heard. Repetition may also occur within the context of a trill or tremolo figure.

- The tone row may, within the confines of the system, legitimately be used in retrograde (reversed order), inversion (mirroring of each interval), or retrograde inversion (reversed order in mirrored form).

In this composition I most recently wrote, called Dissonant Departure, you’ll see that in the first musical row here I have E, B-flat, A, G-sharp, E-flat, and so on. These are the pitches that I selected, and I tried to be as dissonant in the interval between each of the notes. If you look at the arrows leading down to where it says “chords,” if you’re going to use chords, you should use the three notes or five notes in a row, and then the next three, four, or five notes, and then continue on like that. And, of course, the row that you’re looking at (the “prime”), is the tone row. And what I can do is reverse that row, which is on the bottom staff—D, F, C-sharp, G, B, C, and so on. And that’s the “retrograde.”

It’s nice to have a matrix filled out with the notes you have selected for your tone row. If you look at the matrix here that’s all filled in, the notes on the very top row (the C, G-sharp, E, B-flat, A, and so on), are the notes that I selected in one of my compositions back in my college days—but this is what the tone row was for me. What you do is to also place the numbers in the order that they appear in the chromatic scale, starting with zero as your first note in the row. In this case, I started with Zero, which is “C” and then the next note would be a “C sharp,” so that would be the first note. And the next one would be a D, which would be the second, and so on, and so forth.

If you take a look at the matrix, you see the “P” on the far left, that’s your prime row, and you can come up with all different kinds of variations. The inversion “I” at the top (of the matrix) is (the prime row) basically mirrored. Then the retrograde to the far right, the “R”, means it’s just backward. The melody is being played backward. The “RI” at the bottom is retrograde inversion.

That should give you a little bit of a start. Thanks for listening!

Works Consulted

Aldridge, Rebecca. The Sinking of the Titanic. New York: Infobase Publishing, 2008. Print.

Great Historical Disasters.

“Arnold Schoenberg.” AllMusic by Rovi. Rovi Corp. 2012. Web. 15 May 2012.

<http://www.allmusic.com/artist/arnold-schoenberg-mn0000691043>.

Balducci, Andrea. “Le Sacre du printemps 2 – Sirolo.” 23 August 2009. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 16 July 2010. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Le_Sacre_du_printemps_2_-_Sirolo.jpg>.

Beschloss, Michael and High Sidey. The Presidents of the United States of America. White House Historical Association, 2009. “Franklin D. Roosevelt.” The White House. Web. 2 May 2012. <http://www.whitehouse.gov/about/presidents/franklindroosevelt>.

Blackman, Mary Dave. “Arnold Schoenberg and Twelve-Tone Music – OpenBUCS.” East Tennessee State University. YouTube. 12 Aug. 2013. Web. 15 Apr. 2014.

<http://youtu.be/PT2cIdbRCNc>.

Botstein, Leon. “Modernism.” Oxford Music Online. Grove Music Online. Web. 21 June 2012. Burkholder, Peter J. “Borrowing.” Oxford Music Online. Grove Music Online. Web. 21 June

2012.

Cage, John. 4’33”. 1952. YouTube. 15 Dec. 2010. Web. 17 July 2016.

<http://youtu.be/3fYvfEMUJl8>.

—. Indeterminacy: New Aspect of Form in Instrumental and Electronic Music. 1959. Perf.

John Cage and David Tudor. YouTube. 2 Jan. 2016. Web. 17 July 2016.

<https://youtu.be/bT3guS2QRxY>.

—. Rozart Mix. 1965. Perf. Ensemble Musica Negativa. Cond. Rainer Riehn. June 1971.

Music Online: Classical Music Library. Alexander Street Press. Web. 22 Oct. 2014.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/1 481824>.

Carpenter, Alexander. “Schoenberg’s Erwartung and Freudian Case Histories: A Preliminary Investigation.” Discourses in Music. Vol. 3, No. 2. 2001-2002. Web. 5 Sept. 2012.

<http://www.discourses.ca/v3n2a1.html>.

“Computers in Music.” The Oxford Dictionary of Music. 2nd ed. rev. Eds. Michael Kennedy Joyce Bourne. Grove Music Online. Web. 22 June 2012.

Construction tools sign, used with permission from Microsoft. “Images.” Office. Web. 4 Sept.

2012. <http://office.microsoft.com/en- us/images/results.aspx?ex=2&qu=tools#ai:MC900432556|mt:0|>.

Crouch, Tom D. Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2004. Print.

David Tudor and John Cage at Shiraz Art Festival. 1971. Cunningham Dance Foundation Archive. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 22 Jan. 2011. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:TudorCageShiraz1971.jpg>.

Debussy, Claude. “Claire de Lune.” Suite bergamasque. 1905. Perf. Wolfgang Sawallisch and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Minato-Mirai Hall, Yokohama, Japan. May, 1999. YouTube. 24 Oct. 2007. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://youtu.be/gElTKhbnQxU>.

—. Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun. 1894. Perf. L’Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal.

Cond. Charles Édouard Dutoit. YouTube. 22 Jan. 2011. Web. 22 Oct. 2014.

<http://youtu.be/bYyK922PsUw>.

Degas, Edgar. Ballet Rehearsal on Stage. 1874. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 31 May 2011. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edgar_Germain_Hilaire_Degas_033.jpg>.

Duffy, Michael. Firstworldwar.com: A Multimedia History of World War One. 2000. Web. 29 April 2012. <http://www.firstworldwar.com/>.

“Edgard Varèse.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 21 June 2012.

“Edgard Varése.” Last.fm. 4 July 2012. Web. 21 April 2012.

<http://www.last.fm/music/Edgard+Var%C3%A8se>.

Journey. “Atonal Music Explained in a Nutshell.” YouTube. 13 May 2010. Web. 1 Sept.

2012. <http://youtu.be/i5tmK6xcDws>.

Hyacinth at en.wikipedia. “Prime, retrograde, (bottom-left) inverse, and retrograde-inverse.” 9 Nov. 2011. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 10 May 2012. Web. 1

Sept. 2012. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:P-R-I-RI.png>.

“Igor Stravinsky.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 21 June 2012.

“Impressionism.” The Oxford Dictionary of Music. 2nd ed. rev. Eds. Michael Kennedy Joyce Bourne. Grove Music Online. Web. 21 June 2012.

“Interview with Arnold Schoenberg.” YouTube. 8 July 2007. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/Fd61jRM6Chw>.

“Introducing the Pentatonic Scale.” 8notes.com. Red Balloon Technology Ltd., 2000. Web. 9 May 2012. <http://www.8notes.com/articles/pentatonic_scales.asp>.

Ives, Charles. 114 Songs by Charles E. Ives. 1922. Scott Mortensen. “Songs.” A Charles Ives Website. 2002. Web. 5 Sept. 2012. <http://www.musicweb- international.com/Ives/WK_Songs.htm>.

Ligeti, György. “Artikulation.” 1958. YouTube. 28 May 2012. Web. 15 May 2012.

<http://youtu.be/71hNl_skTZQ>.

Man, Ray. Portraitfoto von Arnold Schonberg. 1927. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 5 May 2012. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arnold_sch%C3%B6nberg_man_ray.jpg>.

Manning, Peter. “Computers and Music.” The Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham. Grove Music Online. 22 June 2012.

Moore, Gillian. “Edgard Varése: In Wait for the Future.” The Guardian. 8 April 2010. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2010/apr/08/edgard-varese- national-youth-orchestra>.

“Motion picture.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 21 June 2012.

“Music and Technology.” Exploring the World of Music. Prod. Pacific Street Films and the Educational Film Center. 1999. Annenberg Learner. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://www.learner.org/resources/series105.html>.

“Musique concrète.” The Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham. Grove Music Online. 22 June 2012

Naviglec. “12 Tone Serialism.” 25 Nov 2009. YouTube. Web. 1 May 2012.

<http://youtu.be/c6fw_JEKT6Q>.

Rose Sanderson. Bain News Service.10 Feb. 1913. George Grantham Bain Collection.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, ggbain12483. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 21 May 2012. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rose-Sanderson-Votes-for-Women.jpeg>. Samson, Jim. “Avant-garde.” Oxford Music Online. Grove Music Online. Web. 21 June 2012.

“San Francisco earthquake of 1906.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition.

Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 21 June 2012.

Schoenberg, Arnold. “Bar 1-5 from Schönbergs Opus 24, 1.” 1920-23. Ed. Boris Fernbacher.

Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 10 Apr. 2010. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sch%C3%B6nbergOp24-1.png>.

—. “Nacht.” Pierrot Lunaire. 1912. YouTube. 11 Sept. 2007. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/u6LyYdSQQAQ>.

“Serialism, Serial Technique, Serial Music.” The Oxford Dictionary of Music. 2nd ed. rev. Eds.

Michael Kennedy Joyce Bourne. Grove Music Online. Web. 21 June 2012.

Stravinsky. Bain News Service. N.d. George Grantham Bain Collection. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, ggbain 32392. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 13 Oct. 2011. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Igor_Stravinsky_LOC_32392u.jpg>.

Stravinsky, Igor. The Soldier’s Tale. 1918. Perf. The Gropius Ensemble. Einav Cultural Center, Tel Aviv, Israel. 23 Apr. 2008. YouTube. 23 Apr. 2008. Web. 1 Sept. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/uRpg6WTi15s>.

Stravinsky, Igor and Vaslav Nijinsky. The Rite of Spring. 1913. Perf. The Joffrey Ballet. 1987.

YouTube. 30 June 2010. Web. 1 Sept. 2012. <http://youtu.be/jF1OQkHybEQ>.

Taylor, Nick. “A Short History of the Great Depression.” N.d. New York Times. Web. 7 May 2012.

<http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/g/great_depression

Thompson, Kristin, and David Bordwell. Film History: An Introduction. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2010. Print.

Walsh, Stephen. “Stravinsky, Igor.” Oxford Music Online. Grove Music Online. Web. 22 June 2012.

Whittall, Arnold. “Serialism.” The Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham. Grove Music Online. 22 June 2012.

“Whole tone scale.” Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary. Eds. Richard Cole and Ed Scwartz. 1996. Web. 14 Apr. 2012. <http://dictionary.onmusic.org/terms/3932- whole_tone_scale>.

Wright Aeroplane. 1908. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 3 Aug. 2012. Web. 1

Sept. 2012. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wright-Fort_Myer.jpg>.

Wright, Craig. “Lecture 22: Modernism and Mahler.” Music 112: Listening to Music. Yale University’s Open Yale Courses. 2012. Web. 9 April 2012.

<http://oyc.yale.edu/music/musi-112/lecture-22>.

—. “Lecture 21: Musical Impressionism and Exoticism: Debussy, Ravel, and Monet.” Music 112: Listening to Music. Yale University’s Open Yale Courses. 2012. Web. 9 April 2012. <http://oyc.yale.edu/music/musi-112/lecture-21>.

“World War II.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 21 June 2012.

“Woman suffrage.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 21 June 2012.

“World War I.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 21 June 2012.