5 Chapter 5

The Romantic Period, 1810-1910-ish

The Romantic Period video Intro & 2nd chap: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UAKWm1LfSes

By Bethanie L. Hansen

“Opera is when a guy gets stabbed in the back and, instead of bleeding, he sings.” –Ed Gardneras Archie,Duffy’s Tavern

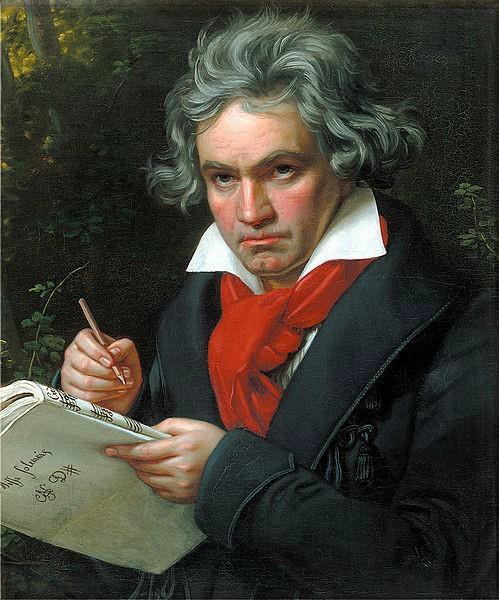

Figure 5.1 Joseph Karl Stieler, Beethoven with the Manuscript of the Missa Solemnis, 1820.

Romanticism was a period in the arts and literature that emphasized passion and intuition over reason and logic. The Romantic Period (about 1820-1910) was a time of rebellion against structure, traditional expectations, and rationalism. The use of the term Romanticism began in literature; authors used the term to describe nineteenth-century expressive literature, like short stories and novels. Composers too embraced this term to describe their music written during this era. Although the music of the Romantic era was generally innovative and emotionally intense, this period produced composers who were highly individualistic and widely known for their own special approaches to composing.

The Romantic era began with Beethoven and also included Chopin, Wagner, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Verdi, Mahler, Strauss, Liszt, Berlioz, Mussorgsky, and Tchaikovsky, among others. We know many exceptional composers from this period because much of what was produced survives and is commonly performed today. Composers of the Romantic era sought to communicate emotion and expression over the use of form, fueled by the societal and political changes taking place around them. While the Classical period thrived on formulaic music that pleased courtly audiences, Romantic period music gained

momentum through the growing popularity of public performances and composers’ using musical tools in new ways.

Relevant Historical Events

After the Renaissance and Reformation, Western Europe began to experience social, political and economic revolution. The Catholic Church that had dominated previous centuries no longer ruled society, as its influence had diminished from the sixteenth century onward. Protestants believed more in performing good works as signs of mortality, which created a Protestant work ethic and emphasis on humanism. For the first time, people focused on the moral worth or value of individuals during their earthly lives. People began to think about having “good” character and enjoying a high quality of life. This change contrasted the “afterlife” emphasis of previous centuries.

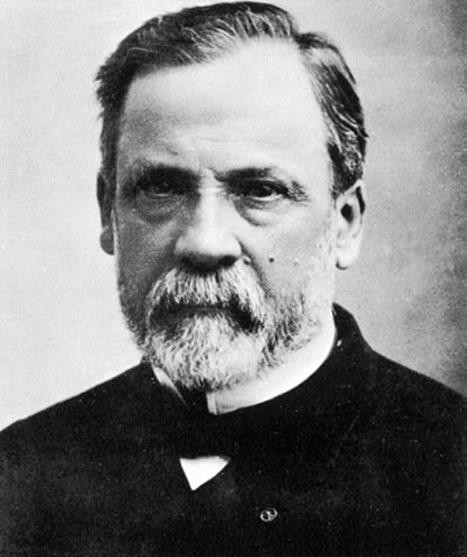

People worked to learn and develop themselves, and medical and scientific innovation blossomed. An unprecedented sudden population boom occurred in Europe that doubled the population to four hundred million. This population boom was mostly the result of increased knowledge of anatomy, disease prevention, and basic health care. Louis Pasteur (1822-95), a French scientist, discovered new theories about germs and bacteria. Pasteur invented the rabies vaccine, developed a method to stop milk and wine from souring (now referred to as pasteurization), and solidified theories about germs. Pasteur and other scientists developed the fields of microbiology and chemistry in beneficial ways.

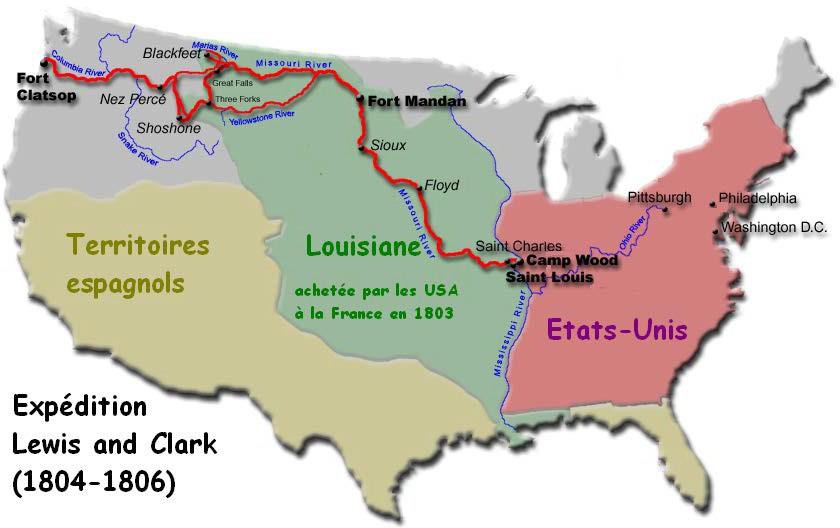

In America, the early 1800s were years of expansion and migration west. In 1803, the United States purchased a piece of land from France known as the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of the United States. Lewis and Clark traveled west in 1804 to discover and document the countryside all the way to the Pacific Ocean, through what we now know as Idaho and Washington. The California Gold Rush began in 1848. The first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, making it possible for people to travel

Figure 5.2 Felix Nadar, Louis Pasteur, 1978. Black and white photograph of French biologist Louis Pasteur (1822-95).

America freely pursued its ambitions and take command of its own destinies. The first national park, Yellowstone, was established in 1872; in 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner declared that there was no longer an “American Frontier.” Significant inventions and developments took place during the nineteenth century that modernized Western civilization. The Figure 5.3 Urban, Expédition Lewis, and Clark, 2005. This is an image depicting the Lewis and Clark Expedition route to explore uncharted areas of the western United

The second Industrial Revolution began in 1871, while twenty-six million people in India and thirteen million people in China died from famine. There was a significant disparity between the West and the rest of the world. During these years, wealth and prosperity in the United States expanded to create the “Gilded Age” (circa 1870-96). Westerners “discovered” and explored large land masses worldwide and developed many new modes of transportation. Automobiles with steam and electric engines were created during this century, leading to early gas-powered cars at the end of the 1800s.

Political Influences

The world political climate in the early 1800s affected the arts and human expression significantly. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-78), the French philosopher, taught theories of social reform and opposed political tyranny. These ideas became the theme of common people in many places and influenced liberal and revolutionary events of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Figure 5.4 Jacques-Louis David, Portrait of Napoleon in his study at the Tuileries, 1812. This painting depicts Napoleon in the uniform of the Imperial Guard horse hunters.

The American Revolutionary War (1775-83) shifted the focus from a ruling monarchy to empowered civilians. The French Revolution (1789-99) began a period of political upheaval throughout much of Europe that lasted for many years. Features of this revolution included the pursuit of empowerment of the common individual, struggles over territory and power, and the leadership of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte worked his way up French military ranks to eventually crown himself as Emperor of the French in 1804. In many countries, the idea that common people had a “voice” and could challenge governments took hold, resulting in turbulence between tradition, idealism, and revolution. Beethoven’s music categorized as his “middle” period was composed during this time and was heavily influenced by the turbulence and revolutionary ideas around him.

The influence of political changes on the arts is evident in the type of music Beethoven composed beginning with theEroica Symphony(Symphony No. 3, 1804). The Eroica was a large-scale dramatic piece Beethoven composed and dedicated to revolutionary ideas. The symphony had first been dedicated to Napoleon and called “Buonaparte,” until the leader declared himself to be the Emperor. At this news, Beethoven feared that Bonaparte would simply become another political tyrant, and he changed the title to Eroica, or “Heroic.” The piece followed Classical period structure but introduced more grandiose musical ideas on a large scale in four smaller parts, or movements. The Eroica was the beginning of musical change for Beethoven and other composers. This work was so significant that it is frequently considered the piece that changed Beethoven’s focus and began Romanticism in music.

- Click to view a performance of the first movement from the Eroica, performed by the Wiener Philharmoniker Orchestra, conducted by Leonard Bernstein.

- Click to view the BBC 2003 production of Eroica, based on Beethoven’s composing ofthe symphony and its political context. (start at 14:00min & end at 18:40min), Sym #3 to mark the transistion into the Romantic Era.

Political developments in America and France introduced new governmental ideas based on constitutions and democracy. The French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville wrote two significant works discussing government based on the will of the people, Democracy in America (1835), and The Old Regime and the Revolution (1856). The American and French revolutions set a precedent for future political ideals throughout the modern world.

Social Influences

While the masses were empowered by political changes, industrial development began to change the way people interacted, where they lived, and how they worked. The Industrial Revolution, which began in Great Britain, swept through cities and towns, bringing manufacturing industries with smokestacks and large machinery. The industrialized society included a focus on the individual rather than the group, as well as the espousing of intellectually-determined “rights” by people or groups rather than dominance by divinely- appointed authorities. A large percentage of agricultural workers moved from farms into cities. Machines were used to increase productivity beyond what had been obtained through manual and animal-assisted work.

Many people in both Europe and America began to feel helpless or hopeless due to oppressive and inhumane working conditions. Children commonly worked in factories.

Additionally, people began to spend their time in designated ways, such as “at work,” and in leisure pursuits. Work time became separate from family and socialization. Previously, families had been cooperative groups who worked together and benefitted together.

Industrialization took the collective family economy and created consumers who either owned businesses or depended on them.

Cultural Influences

Figure 5.5 Francisco Goya, The 2nd of May 1808 in Madrid: the charge of the Mamelukes, 1814.

Artistic professions emerged in the nineteenth century out of necessity, because music and other arts were no longer solely supported by the patronage system. As composers created more challenging works, extremely skilled professional performers were needed. Artists began to depict scenes of loneliness, isolation, and discontent, as well as extreme emotions like fear and insanity later in the century. The chaos and terror of war were illustrated by visual artists like Francisco Goya of Spain (see figure 5.5). In war-related art, dismal gray colors portrayed the mood of battle, and brighter colors depicted characteristics such as lost innocence, death, and strife.

Artistic expression reflected the conditions of the times. In the latter half of the Romantic period, Carnegie Hall (1891) was built in New York. Modern transportation allowed musicians and audiences to travel, bringing magnificent performers to remote areas.

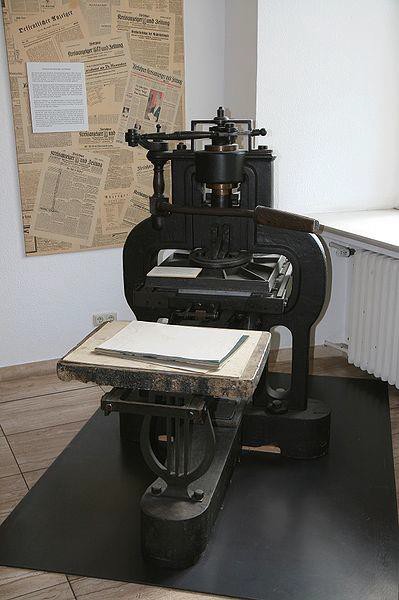

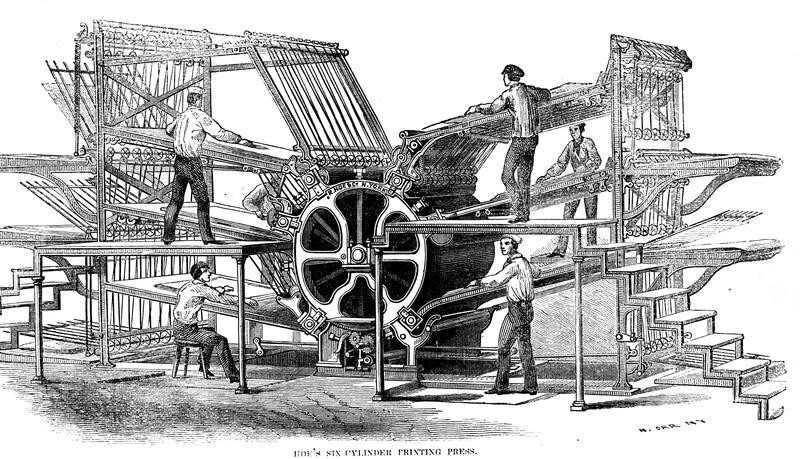

Literature developed, including Gothic novels, such as Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818); fiction, like the Grimm brothers’ Fairy Tales; and the poetry of Goethe, Keats, Whitman, Wordsworth, and Edgar Allan Poe. Automation of the printing press between 1812

and 1818, due to the new steam-powered press of Friedrich Koenig, led to rapid printing on both sides of a page simultaneously (Bolza).

Printing technology continued to progress, as the rotary press of 1843 increased speed and efficiency. New presses produced printed pages ten times faster than hand presses, which advanced the creation of mass-produced newspapers and books. Widely available printed materials increased literacy throughout the century.

Printing technology continued to progress, as the rotary press of 1843 increased speed and efficiency. New presses produced printed pages ten times faster than hand presses, which advanced the creation of mass-produced newspapers and books. Widely available printed materials increased literacy throughout the century.

Figure 5.6 Stanhope hand-powered printing press, the late 1770s.

Figure 5.7 N. Orr, Hoe 6-Cylinder Motored Rotary Printing Press, 1864.

Figure 5.8 Ford Maddox Brown. Romeo and Juliet, 1870. This oil on canvas painting portrays Romeo and Juliet meeting on the balcony of Juliet’s home, kissing.

Composers were heavily influenced by literature, and many included themes and stories in their works. Examples of this connection include Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet (1870), based on Shakespeare’s play, and “Der Erlkönig” (1813) by Franz Schubert, based on a poem by Goethe. “Der Erlkönig” is a frantic piece about a father rushing his ill child to help while speeding along on a horse, which ends in the child’s death by supernatural means. This piece exemplified the extreme emotions of terror, insanity, and hysteria popular in the Romantic Era.

Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2l8llogGKto

Ballet : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WZ-i188cmdg

“Nutcracker” highlights: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0WXDptnrziE

Defining Characteristics of Romanticism in Music

Music during the Romantic period became wildly expressive and emotional.

Composers experimented with new chords, unusual chord progressions, dissonance (notes that are close together and seem to create tension), and smaller motifs for thematic development. Music began to include creative and innovative harmonies. Symphonies and operas were still the mainstay of performance music, but smaller works that used to be confined to private performances also began taking the stage—such as sonatas, lieder

(German songs), and other works. Instrumental program music (music that tells a story without words) mimicked opera by portraying scenes and stories through non-vocal music.

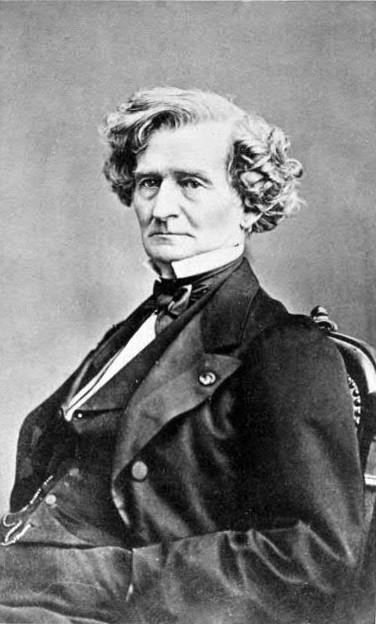

Composers of the Classical period produced music that often sounded similar, like Mozart and Haydn, but composers in the Romantic period distinguished themselves by developing unique personal styles, practices, and modes of expression. For the first time, rather than characterizing an era by a set of practices and trends, this period began to present composers as individuals. Common themes during this period included intense emotions, nationalism, extreme perceptions of nature, exoticism (focus on faraway places such as Asia), and the supernatural or macabre. Symphonie Fantastique (1830), by Franc, Hector Berlioz, is an example of many common Romantic themes. The symphony lasts forty-five minutes and portrays the story of a young artist who envisions unrequited love, jubilant dancing at a ball, a pastoral nature scene, anger and murder, an execution, a burial, and a “Witches’ Sabbath.” (Ex: dissonance & abrupt emotion changes)

Composers of the Classical period produced music that often sounded similar, like Mozart and Haydn, but composers in the Romantic period distinguished themselves by developing unique personal styles, practices, and modes of expression. For the first time, rather than characterizing an era by a set of practices and trends, this period began to present composers as individuals. Common themes during this period included intense emotions, nationalism, extreme perceptions of nature, exoticism (focus on faraway places such as Asia), and the supernatural or macabre. Symphonie Fantastique (1830), by Franc, Hector Berlioz, is an example of many common Romantic themes. The symphony lasts forty-five minutes and portrays the story of a young artist who envisions unrequited love, jubilant dancing at a ball, a pastoral nature scene, anger and murder, an execution, a burial, and a “Witches’ Sabbath.” (Ex: dissonance & abrupt emotion changes)

“Songe d’une nuit du Sabbat” or “Dreams of a Witches’ Sabbath.”

Critical Listening

“If a composer could say what he had to say in words he would not bother trying to say it in music.”– Gustav Mahler (Blaukopf 171)

Only a brief sampling of Romantic music is presented in this chapter, although hundreds of diverse works were composed during this era. As you listen to Romantic music, use the key music terms as tools to describe what you hear. Continue practicing to remember concepts, become more comfortable identifying traits in the music, and become able to apply your skills to new pieces that are not covered in this course. Keep in mind the general traits of Romantic music previously discussed, including intense emotions, nationalism, extreme perceptions of nature, exoticism, and the supernatural or macabre.

Listen for these traits as you explore the music of the four composers highlighted in this chapter: Beethoven, Wagner, Liszt, and Verdi.

Listening Objectives

Your listening objectives during this unit will be to:

- Identify any Romantic period traits in the music.

- Listen for instrumentation and timbres, including voices or instruments that are performing.

- Observe small motifs in music and listen for their repetition, manipulation, change, and overall presentation throughout a piece, including the return of familiar musical sounds and/or melodies that could signal a repeated section in the larger form of the work.

- Listen for dynamic and tempo changes, including sudden loud or soft passages, and sudden faster or slower sections.

- Practice describing these observed concepts using the music terms instrumentation, timbre, texture, tempo, dynamics, and form.

Key Music Terms

Instrumentation describes what kind of instrument or voice produced the music.

Instrumentation describes what kind of instrument or voice produced the music.

During the Romantic period, the piano continued to become a prominent instrument. Other instruments became standardized, such as the saxophone (which was patented in 1846), the Boehm flute, and the Moritz tuba. Instruments were expected to produce sound in their extreme upper and lower ranges as needed. Specific instruments were used to communicate ideas to represent story characters or returning themes in program pieces like Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique.

Symphonie Fantastique , Franc Hector Berlioz, “Dreams of a Witches’ Sabbath.”

Timbre, or tone quality, describes the quality of a musical sound. Timbre is generally discussed using adjectives, like “bright,” “dark,” “buzzy,” “airy,” “thin,” and “smooth.” Many different adjectives can be effectively used to describe timbre,

Timbre, or tone quality, describes the quality of a musical sound. Timbre is generally discussed using adjectives, like “bright,” “dark,” “buzzy,” “airy,” “thin,” and “smooth.” Many different adjectives can be effectively used to describe timbre,

based on your perceptions and opinions about what is heard in the sound. Romantic composers often explored varying timbres to create specific moods and emotions—such as the terror communicated by shrill, high-pitched, dissonant tones. Timbre at times seemed edgy, rough, or shrill. At other times, timbres were warm and very lush as in Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet.

Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2l8llogGKto

Texture is a term that describes what is going on in the music at any moment. Musical texture is the way that melody, harmony, and rhythm combine. Texture can

Texture is a term that describes what is going on in the music at any moment. Musical texture is the way that melody, harmony, and rhythm combine. Texture can

be described in musical terms, like monophonic, homophonic, and polyphonic—or with adjectives, like “thin,” “thick,” and “rich.” Much of Romantic period music was homophonic and revolved around the melody or melodic statements.

Melody is a recognizable line of music that includes different notes, pitches, and rhythms in an organized way. A melody may be simple or complex, and it may be

Melody is a recognizable line of music that includes different notes, pitches, and rhythms in an organized way. A melody may be simple or complex, and it may be

comprised of smaller pieces called “motifs.” Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, for example, includes a melody based on repeated motifs. Listen to an example of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, and take notice of the motif first heard in the first four notes of the piece, as you hear it pass by. After several statements of this smaller motif, the smaller motivic pieces begin to form a more recognizable melody. The melody stands out from the background musical material because it is stronger, louder, and more aggressively played.

Beethoven – “Symphony 5” (listening)

Harmony is created when at least two voices perform together. Two different types of harmony generally exist in music—homophony, and polyphony. One additional

Harmony is created when at least two voices perform together. Two different types of harmony generally exist in music—homophony, and polyphony. One additional

musical texture, monophony, does not include any harmony. When considering musical texture, ask yourself these questions:

- What instruments or voices am I hearing?

- Is there a clear melody, with supporting harmony (homophony)? Or do I hear smaller segments of a melody, broken up and difficult to follow?

- Are the voices or instruments used in traditional, predictable ways, or do I hear unusual/extreme sounds?

Tempois the speed of the music. Tempo may also be called “time.” Tempo can change during a piece to add expression, such as a rubato(slowing of the tempo, almost free time briefly in nature).

Tempois the speed of the music. Tempo may also be called “time.” Tempo can change during a piece to add expression, such as a rubato(slowing of the tempo, almost free time briefly in nature).

Speeding up the tempo is called an accelerando, and slowing down gradually is called a ritardando. Romantic period music explored the extremes of tempo fluctuation, often changing tempos throughout a piece to communicate emotion.

Dynamics are changing volume levels of musical sounds. Dynamics can range from softer than piano (soft or quiet) to above forte (loud). Dynamics can also change,

Dynamics are changing volume levels of musical sounds. Dynamics can range from softer than piano (soft or quiet) to above forte (loud). Dynamics can also change,

getting louder (crescendo) and getting softer (diminuendo). Dynamics and changing dynamics give the music expression, make it interesting, and add variety. Dynamics are another tool exploited by Romantic period composers to create expression and emotional communication. Sudden dynamic extremes were commonly used.

Form is the organization and structure of a musical selection. The form of work may include repeating large sections, repeating a theme or motif, or non-repeating

Form is the organization and structure of a musical selection. The form of work may include repeating large sections, repeating a theme or motif, or non-repeating

sections. Large parts within a musical form are usually labeled with capital letters like “A” and “B.” Within these larger sections, smaller parts may be labeled with lower-case letters like “a” and “b” to further designate repeated and non-repeated sections. In the Romantic period, forms became both larger and smaller than those of previous periods. The multi- movement symphony continued to develop, along with variations on existing ideas—such as the creation of an overture without any connection to an opera—and symphonic poems that expressed ideas without lyrics or an underlying story line. Forms were much more flexible during this period, with the expression or story sometimes more important than following a specific form.

Composers

Ludwig van Beethoven (Thayer 494) Music Quotes “…music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy, the wine which inspires one to new generative processes, and I am the Bacchus who presses out this glorious wine for mankind and makes them spiritually drunken.”

Ludwig van Beethoven

Figure 5.10 Christian Hornemann, Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven, 1803.

Beethoven was generally considered the first Romantic composer. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) began his music career as a German court composer and musician but moved to Vienna around 1792, where he stayed for the rest of his life. Beethoven made a living writing and selling music; he was one of the first composers to make a business independently composing without reliance on the patronage system. Throughout his life, Ludwig van Beethoven experienced challenges and political events that inspired him to portray emotion, conflict, and drama in his music. Beethoven’s father was a failed musician with little professional success who became an alcoholic. It is believed that he forced Ludwig to emulate Mozart’s skills; Mozart was only fourteen years older than Beethoven. Ludwig’s mother died in his youth, leaving him to help raise his siblings due to his father’s incapacitation.

When Ludwig traveled to Vienna at age twenty-two, he studied with Haydn and several other composers. He was taught counterpoint—a specific method of composing common to the Classical period—and various functional composing techniques. Although

Haydn and others recognized Ludwig’s obvious talent and exceptionally powerful piano performance abilities, they all struggled to teach Beethoven. He was a difficult student who disregarded rules and authority figures. To complicate matters, he began to gradually lose his hearing in 1796, at the age of twenty-six.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1bsZzUVWJc,(Beg to min 1:50 / End at min13:45)

To develop ideas and work at composing throughout the day, Beethoven always carried a music notebook. He kept many notebooks throughout his life, several of which survive and are housed in the Berlin State Library. In his notes, Beethoven often began with a single musical motif or idea and worked with it until he developed the idea in detail and worked it into an entire piece of music. In all, Beethoven composed nine symphonies, thirty- two piano sonatas, nine piano trios, five piano concertos, one opera, two large choral works, and several other pieces.

Beethoven’s music can be divided into three distinct periods within his composing career.

- Early Beethoven music (to 1802) generally fit under Classical period techniques and traditions and was influenced by Mozart and Haydn. Piano Sonata No. 14 in C sharp minor, “Moonlight,” Op. 27 Moonlight Sonata (1801)is one example from this period. Listeners may have heard about the first movement in popular films or television programs (Adagio Sostenuto).

- Middle-period music (1802-14) broadened to a more expressive style and included more significant works such as http://”Fur Elise”, Beethoven. & Beethoven’s 3rd Symphony (Eroica), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KEQIwm4eNoc, which marked the transition into the Romantic Era. Some examples from this middle period also include “Allegro Con Brio,”fromSymphonyNo.5,Op.67 (1808),https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9aDEq3u5huA, and StringQuartetNo.11inFMinor“Serioso”,Op.95 (1810).

- Late Beethoven’s pieces (1815-27) were more serious and personal, likely due to Beethoven’s deafness late in his life. In his late period, Beethoven retreated to more intellectual composing techniques, such as the use of Bach-like fugues, likely due to his total deafness and reclusive nature. 9th Sym. MOV.IV, “Ode To Joy”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uooe16ILaPo

A comparison between Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 and Haydn’s SymphonyNo.94“Surprise” illustrates the extreme impact Beethoven had on the music world in his day. The Fifth Symphony is intense, dramatic, and edgy when compared to the “proper,” polite, and dignified Haydn piece. Audiences of the time would have been shocked by the extremes of Beethoven’s music. Rather than expressing musical restraint, Beethoven opened the floodgates of emotion and communicated stronger ideas than had ever taken the stage previously.

As you listen to the Allegro con Brio from Symphony No. 5, exercise your developing music analysis skills. Describe the instrumentation by naming instruments that you hear. There are a lot of stringed instruments in this piece, but at times, you will hear the higher violins or the lower cellos and basses, and you will also hear timpani drums. Listen particularly for extreme ranges—very high and very low pitches. Observe the texture of the work, as melodies first enter in monophony, or unison, then play back and forth with a bit of polyphony (from about 0:07 to 0:16) leading into homophony. The influence of Bach’s fugue style, which Beethoven learned as a young organ student, can be heard early in this piece through the brief polyphony. Throughout the piece, listen for extreme dynamic changes, involving either the entire ensemble or just a few instruments. Notice tempo changes as the music seems to speed up, slow down, or stop altogether. Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 is an excellent example of Romanticism and expression that flies in the face of traditional order and restraint.

For additional information about Beethoven, visit the following websites:

- Encyclopedia Britannica: http://www.britannica.com/biography/Ludwig-van-Beethoven

- Raptus Association for Music Appreciation: http://raptusassociation.org/index.html

- Ludwig van Beethoven Site: http://www.lvbeethoven.com/

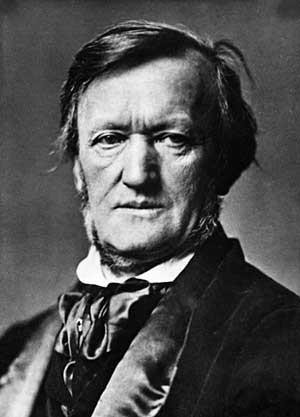

Richard Wagner

Figure 5.11 Franz Seraph Hanfstaengl,. Richard Wagner (1813- 1883), 1871.

Wagner quote: “I must have beauty, splendor, and light. The world ought to give me what I need!”, Some found him a bit egotistical. Ex; private concerts at home.

The Romantic Period video chap 5 “concerts at home”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UAKWm1LfSes

Richard Wagner (1813-83) was a composer who wrote large opera-style works. He was born in the Jewish Quarter of Leipzig, a city known for its great German musicians and writers like Bach and Goethe. Wagner’s father died six months after he was born.

He was then raised by his mother and stepfather, actor and play-write Ludwig Geyer, who died when Richard was eight. Before his death, Geyer brought Richard into the theater industry. Richard later pursued music lessons in order to set his own plays to music. Richard had a natural gift of playing music“by ear,” which means to play without written music. In just a few years, Richard transcribed others’ complicated pieces of music and began composing his own works. He was inspired by Beethoven and composed a symphony similar to Beethoven’s 9th after only five years of music lessons and one year of university studies.

Wagner’s career was a turbulent one. His first performed opera, Das Liebesverbot, was a failure and even bankrupted the production company which sponsored it. He struggled financially and married an actress, with whom he experienced a torrid relationship. Wagner moved from city to city trying to promote his operas, fleeing with his wife to Paris at one point just to avoid debt collectors. It was several years before anyone accepted his musical works for production, but Wagner persevered with the determination that he would eventually succeed.

When success finally came, Wagner moved back to Germany to produce his operas and was able to pay back old debts and take a leadership position in local music activities. He could not resist becoming a political activist, and he wrote anti-aristocratic articles for the local radical newspaper. He also physically participated in leftist rebellion activities and fled Germany a second time, to avoid arrest. During his exile, Wagner continued composing operas, including Lohengrin, and writing literary works, including Art and the Revolution. The Lohengrin opera was sent back to Dresden where it was performed in Wagner’s absence and thrilled audiences. As a result of gaining King Ludwig II of Bavaria as a patron of his operas, Wagner was eventually pardoned and allowed to return.

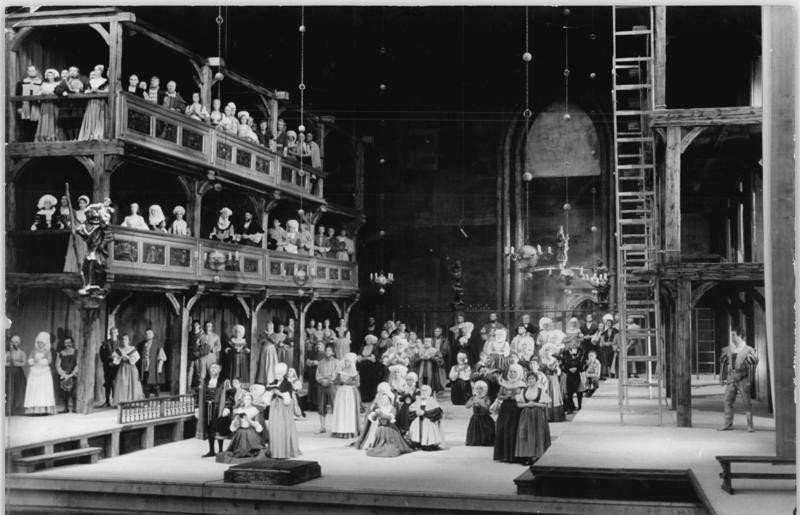

Figure 5.12 Wallmüller, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg by Richard Wagner, opera performance, 1960.

Music by Richard Wagner was extremely dramatic. Many of his works are also very long. “Die Meistersinger” (1862) opens an opera that has three acts and

lasts five hours. The Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg) opera is commonly performed and popular today. In his large works, Wagner developed a type of melody he called the “leitmotif.” Leitmotifs were themes associated with places, characters, or ideas in his dramas. This tool gave audience members something familiar to identify when watching his performed works. Wagner also named his tendency to write very large and dramatic operas, calling them “Gesamtkunstwerk,” or total works of art. He wrote both the libretto (the storyline and lyrics) and the music for all of his staged works, which was different than most other composers who hired others to write their libretti. As illustrated in the photograph in this section, Wagner’s operas also involved constructed sets and large choruses.

Wagner-“Die Meistersinger” tutorial: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDi44y5LKl8 (Beg-7:30m)

As you listen to TheRideoftheValkyries (1854) by Wagner, continue exercising your skills by analyzing the music. First, listen to a few minutes of the piece for your overall first impression. Determine whether the music has a steady or changing tempo. Throughout the piece, listen for extreme dynamic changes, involving either the entire ensemble or just a few instruments. Describe the instrumentation and/or voices by naming instruments and vocal parts that you hear. High-range female singers are sopranos, mid-range female singers are mezzo-sopranos or altos (the valkyries, Norse superwomen, angels of death, riding horses in the sky), mid-range males are tenors or baritones, and low-range males are basses. There are a lot of stringed instruments in this piece, but at times, you will hear other instruments. Listen particularly for extreme ranges—very high and very low pitches.

Observe the texture of the work. Wagner typically composed thick, rich harmonies underneath the melody that sounds driven or heroic. Determine whether you hear an influence from Beethoven in this music. Wagner’s opera changed the philosophy of opera and presented key Romantic traits but profited from the inspiration of other composers during his lifetime.

Franz Liszt

Figure 5.13 W. & D. Downey, Photographers, Franz Liszt, ca. 1880.

Franz Liszt (1811-86) was a Hungarian pianist and composer. His father worked for Prince Esterhazy and was a skilled cellist. As a resident in the palace, Franz observed court concerts and impressive musicians. At five, he began taking piano lessons from his father, and at eight, he began composing his own music. He performed a public concert at age nine, which inspired local dignitaries to pay for his education. Franz studied in Vienna with Czerny, one of Beethoven’s former students, and Salieri, the Viennese Court music director.

Liszt also studied in Paris, afterward touring Europe to perform for dignitaries at age thirteen. When he was only fourteen years old, Liszt’s first and only opera was performed. His father accompanied him during his performance tours and died of typhoid fever during a trip to Italy.

Franz Liszt was a European traveler with diverse interests and extreme abilities, which at times presented challenges for him. Franz suffered from anxiety and depression that impacted his life significantly. In 1828, at age seventeen or eighteen, his depression after a failed romance caused him such intense illness that others thought he was going to die. An obituary was prematurely printed in the local newspaper. He stopped playing the piano completely for an entire year and longed to become a priest. As he recovered, his interest in political matters was piqued, and he composed a symphony in honor of the 1830 revolution in France. He met Hector Berlioz after attending a performance of SymphonieFantastique and was inspired to transcribe that and many of Berlioz’s works for piano. Liszt met and worked with many other composers, including Chopin, Schubert, and Mahler. He toured Europe again, performing for several years in many countries, lived in Germany for a time, and also lived in Italy.

Liszt was both an exceptional pianist and an outstanding composer. He was the first performer to give long piano concerts and featured the works of many other composers. His role in the Romantic era came from pushing the limits of piano compositions, adding to the harmonic language of the era, and introducing chromaticism (the use of twelve pitches from the chromatic scale rather than eight pitches from a major or minor scale within a piece), developing the orchestral symphonic poem, and using musical themes in unique ways.

Liszt’s use of themes led to Wagner’s “leitmotif” techniques, and his chromaticism led to the tonal changes that occurred in twentieth-century music. Liszt was a friend to other musicians and a teacher to many.

Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody #2 (Lang Lang Piano Perf) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6oGEN7oS2z4

Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody #2 (orchestral version) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=goeOUTRy2es

As you listen to Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, in C minor, S. 244, wrong link(1847) by Liszt, think about your music analysis tools. Begin by listening for tempo, dynamics, and style of the work. This piece is heavily influenced by Liszt’s interest in Hungarian Romani melodies (commonly referred to in Liszt’s time as “gypsy” melodies), which seem both haunting and exciting in the arrangement. Consider the form of this piece and listen for repeated melodies or motives. After you have listened to and described the Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, listen to two other pieces by Liszt to compare their musical traits. The first, Appassionata, etude forpiano in F major (Transcendental etude No. 10), wrong link (1851) is a technique study for pianists to improve skills. The second, Piano Concerto No. 3 in E Flat Major(1839), is a piano solo accompanied by an orchestra, designed to show off the pianist’s abilities. These two pieces

have opposing purposes (study vs. performance), but they both demonstrate Liszt’s strong composing skills.

For another interpretation of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No.2, visit the following link:

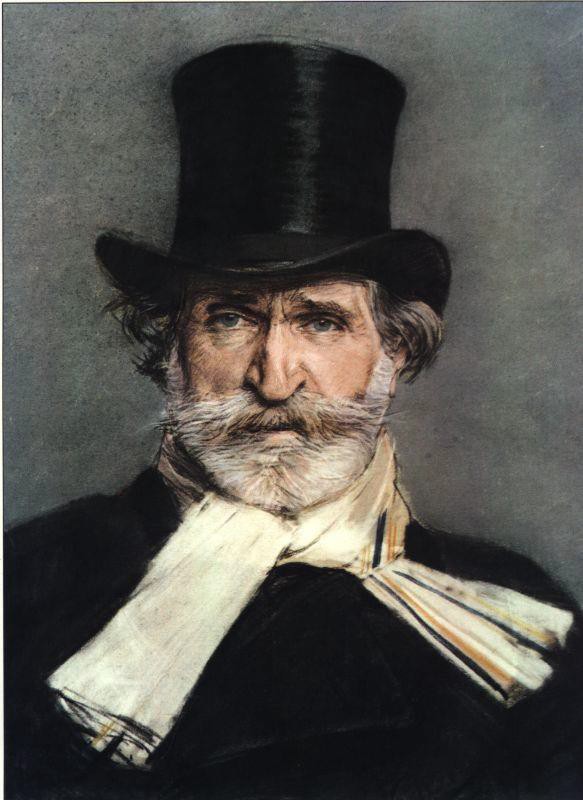

Giuseppe Verdi

Figure 5.14 Giovanni Boldini, Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi, 1886.

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) was an Italian composer born near Parma, Italy in the same year as Richard Wagner. His father was an innkeeper and owned a farm, and the valley where his family resided was impoverished.

Despite their hardships, the Verdi family provided piano lessons to Giuseppe from age four, bought him a ‘spinet’ ? piano, and ensured that he attended the village school. He occasionally accompanied congregations on the organ for his church at age nine. Verdi was denied admission to the Milan conservatory because he played the piano poorly and was too old to attend, so he studied with Vincenzo Lavigna, a composer at the La Scala opera house. Verdi remembered his humble beginnings and called himself the least formally educated of all composers.

Verdi produced his first opera Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio at age twenty-six (1839). Its success sent the production on a small performance tour to two other cities and provided a contract to write three more operas. After he experienced the loss of two children in their infancy and his wife also, Verdi’s second opera (1840) was a failure. His third opera, Nabucco (1841), inspired by the biblical Nebuchadnezzar, was a fantastic success and toured over Europe, Russia, and even Argentina. A theme from this opera, “Va,Pensiero” became an unofficial anthem for Italy. In all, Verdi composed twenty-seven operas during his lifetime.

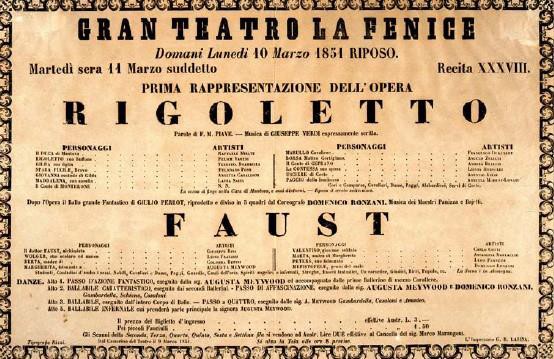

Figure 5,15 Gran Teatro La Fenice. Rigoletto Opera Premiere Poster, 1851.

Personally, Verdi possessed great determination and a solid work ethic. He forced himself to compose two complete operas each year for a period, which involved finding the libretto (lyrics), editing, composing the music, locating suitable singers, conducting rehearsals, and publishing. His intensity and willingness to work paid off, and he eventually became a celebrity. In his later years, he composed operas for Paris that demanded different structures and the inclusion of a ballet. After he believed he had officially retired in 1873, Verdi wrote several works based on Shakespeare’s dramas. A few of these works were his only compositions that appeared to have any musical influence from Wagner, and much of Verdi’s work portrayed his own unique style.

As you listen to Verdi’s “La donna è mobile” from the opera Rigoletto (1851), notice the interesting and “singable” melody of this piece. Verdi possessed the capacity to write memorable singing parts throughout his operas, many of which are commonly used in pop culture today for television commercials, programs, and movies. Right away, the texture of this piece is obvious. The singer’s part is easy to hear, and the background instruments support it fully. “La donna è mobile” has homophonic texture. The instrumentation is a solo voice, accompanied by a full orchestra. Throughout the piece, listen for extreme dynamic changes, involving either the entire ensemble or just a few instruments. Describe the instrumentation and/or voices by naming instruments and vocal parts that you hear. The music itself uses an older form, a strophic pattern (verses that musically repeat with new lyrics each time, like in modern songs) with an orchestra ritornello (repeated section), which originated in the Baroque era. The impact of this selection comes from its text, which conveys the Romantic traits of extreme emotion (love and passion) and drama (trust vs. dishonesty).

|

Italian Text |

English Translation of “La donna è mobile” |

|

La donna è mobile |

Woman is flighty |

|

Qual piùma al vento, |

Like a feather in the wind, |

|

Muta d’accento — e di pensiero. |

She changes her voice — and her mind. |

|

Sempre un amabile, |

Always sweet, |

|

Leggiadro viso, |

Pretty face, |

|

In pianto o in riso, — è menzognero. |

In tears or in laughter, — she is always lying. |

|

È sempre misero |

Always miserable |

|

Chi a lei s’affida, |

Is he who trusts her, |

|

Chi le confida — mal cauto il cuore! |

Who confides in her — his unwary heart! |

|

Pur mai non sentesi |

Yet one never feels |

|

Felice appieno |

Fully happy |

|

Chi su quel seno — non liba amore! |

Who on that bosom, does not drink love! |

Table 5.1 “La donna è mobile,” Italian text and English translation

Impressionism Music with Allysia Van Betuw https://www.pianotv.net/2016/09/impressionist-music/

French Impressionism

Impressionism originated in France as a reaction against the emotional music of the Romantic era. During the late Romantic period, impressionism produced the work of French composer Claude Debussy (“Impressionism”), whose work consisted of special whole-tone and pentatonic scales. The goal of impressionist music was to produce a mood or sense of

something without boldly presenting it. Impressionist music is delicate, sensuous, and calm. In visual arts, the impressionist movement included such well-known artists as Edgar

Degas, Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Painters converged on Paris as the place to develop impressionist art focusing on light and movement. To learn more about impressionist art, visit the Musée d’Orsay website.

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) was the primary composer of impressionism. He worked to communicate images, feelings, and moods through his music rather than by

portraying literal descriptions common to program music. Debussy can be considered the bridge between the Romantic period and the twentieth century, similar to Beethoven being considered the transitional composer between the Classical and Romantic periods. Some of Debussy’s popular piano and orchestral works include Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun (1894), Nocturnes (1899), La Mer (1905), and “Claire de Lune” (1905) a simple melody included in any concert band method book on the market today. Debussy’s impressionist compositions were instrumental works for both piano and orchestra.

The rich texture of Debussy’s music is lush and sensual. The tonality is vague and difficult to pin down, as there is no clear tonal center. The basis of a whole-tone scale is that all notes are equally separated, and there are no patterns of whole and half steps. Instead, all pitches in a whole-tone scale are a whole step apart. Using this and other new scales, Debussy invented unusual harmonies in his music that kept listeners on edge as they waited for the music to settle somewhere.

To learn more about impressionism in music, watch Yale University’s Open Yale Courses lecture “Musical Impressionism and Exoticism: Debussy, Ravel and Monet,” presented by Professor Craig Wright. Viewing this lecture content is not required in the APUS MUSI200 Music Appreciation course and is for additional information only.

Summary of the Romantic Era

The Romantic era was a “coming of age” in the arts. As the world changed and tradition was challenged or abolished, artists changed or broke traditional barriers as well. The Western world changed dramatically, as America became widely settled, the Second Industrial Revolution developed, mass communications and transportation modes were created, and governments were revolutionized. Musical extremes in instrumental ranges, dynamics, tempo, and texture were employed to express an equal set of extremes in emotional states. Composers crafted highly individualized works that sometimes mirrored their own lives and often reflected the world around them. Art and literature focused on intense beauty, morbidity, characterizations of nature, the supernatural and the exotic, and extreme emotion.

Harmony

This week, watch the video “Harmony,” part of the Annenberg Learner video series we will be viewing throughout the text.

Guiding Questions

Identify, describe, and provide examples of various pieces of music from the Romantic period.

- What are some characteristics of early Romantic music?

- What purposes/subject matters are represented in early Romantic music?

- How did forms change during the early nineteenth century?

- Who were some of the significant composers during the 1800s?

- What were some of the noteworthy pieces that were composed during this period?

Self-Check Exercises

Complete the following self-check exercises to verify your mastery of key music terms presented in this chapter.

e. Which of the following traits could describe the music of the Romantic era?

- Expressed extreme emotion

- Expressed nationalism

- Presented supernatural or macabre themes

- All of the above

f.Which composer became prominent during the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte?

- Mozart

- Beethoven

- Ventadorn

- Haydn

g. What type of music is known as a “total work of art,” including both libretto (text) and music all written by the composer?

- Bel Canto

- Gesamtkunstwerk

- Opera

- Symphony

h. What type of music did Verdi compose?

- Operas

- Symphonies

- Sonatas

- Concertos

If you would like additional information about these terms, please review them before proceeding. After you have read the questions above, check your answers at the bottom of this page.

Self-check quiz answers: 1. d. 2. b. 3. b. 4. a.

Additional Listening Examples

Opera

“Overture” from Die Fledermaus, by Johann Strauss II (1874)

Ballet

“Miniature Overture”(track 5) from The Nutcracker, Opus 71, by Tchaikovsky (1892)

Vocal Music, Song

“Nun will die Sonn’ so hell aufgeh’n” from Kindertotenlieder, by Gustav Mahler (1901)

Instrumental Music (small group)

“Papillons” and “Pierrot,” from Carnaval, Op. 9, piano solo, by Robert Schumann (1835)

Instrumental Music (large group)

“Promenade” from Pictures at an Exhibition, by Modest Mussorgsky (1874) “Scherz(o18(L4e1b)haft)” from Symphony No. 4, Op 120, for orchestra, by Robert Schumann

Additional Resources

- Perfect Pitch Related to Language –podcast link. A 2009 study found that speakers

of tonal languages (languages where the meaning of sounds can be differentiated by both shape and pitch) such as Cantonese are more likely to have perfect pitch than speakers of non-tonal languages like English. The link contains a transcript of the podcast.

- Minnesota Public Radio – Streaming radio link. Take a few minutes to listen live to

Minnesota Public Radio. After you have clicked on the site link, then click on Listen, which is located on the upper left-hand side of the page under the Classical heading.

As you are listening, see if you can identify the instruments and the style of music you hear. Listening to classical music radio is a wonderful way to gain a greater understanding of the Western music tradition!

Figure 5.16 Alexy Tyranov, Girl with Tambourine, 1836.

Works Consulted

Arnold, Denis and Barry Cooper. “Beethoven, Ludwig van.” The Oxford Companion to Music.

Ed. Alison Latham. Oxford Music Online. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Barry Millington, et al. “Wagner.” The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Ed. Stanley Sadie.

Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Beethoven, Ludwig van. Piano Sonata No. 14 in C Sharp Minor “Moonlight.” 1801. Perf. André Watts. 1999. Music Online: Classical Music Library. Alexander Street Press. Web. 27 Aug. 2012.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/music- performing-arts/view/work/1478062>.

—. String Quartet No. 11 in F Minor “Serioso”, Op. 95, No.11. 1810. Perf. The New Russian Quartet. YouTube. 4 Dec. 2009. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/qsbMjPztW6U>.

—. Symphony No.3 in E flat major, “Eroica.” 1804. Cond. Leonard Bernstein. YouTube. 26 June 2011. Web. 1 Apr. 2012. <http://youtu.be/W-uEjxxYtHo>.

—. Symphony No. 5 in C Minor. 1808. Cond. Riccardo Muti. Perf. The Philadelphia Orchestra.

1997. Music Online: Classical Music Library. Alexander Street Press. Web. 27 Aug. 2012.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/1 532772>.

“Beethoven, Ludwig van.” The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. rev. Ed. Michael Kennedy.

Oxford Music Online. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Berlioz, Hector. “Songe d’une nuit du Sabbat.” Symphonie Fantastique. 1830. Cond. Yehudi Menuhin. Perf. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. Music Online: Classical Music Library. Alexander Street Press. Web . 11 Apr. 2014.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/9 61102>.

Blaukopf, Herta, ed. Gustav Mahler: Briefe. 2nd ed. Vienna: Zsolnay, 1996. Print.

Boldini, Giovanni. Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi. 1886. National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome.

Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 9 Aug. 2010. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Verdi.jpg>.

Bolza, Hans. “Friedrich Koenig und die Erfindung der Druckmaschine.” Technikgeschichte

34.1 (1967): 79-89. Print.

Brown, Ford Maddox. Romeo and Juliet.1870. Oil on canvas. Delaware Art Museum.

Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 30 Dec. 2008. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:20070205000653!Romeo_and_juliet_bro wn.jpg>.

Bubo bubo. Erste Druckpresse (Stanhope Press) der Zeitung. 1 May 2008. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 28 Aug. 2009. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iserlohn-Druckpresse1-Bubo.JPG>.

“chamber music.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/104861/chamber-music>.

Construction tools sign, used with permission from Microsoft. “Images.” Office. Web. 4 Sept.

2012. <http://office.microsoft.com/en- us/images/results.aspx?ex=2&qu=tools#ai:MC900432556|mt:0|>.

“concerto.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition.

Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/131077/concerto>.

David, Jacques-Louis. Portrait of Napoleon in his study at the Tuileries. 1812. National Gallery of Art. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 26 Feb. 2011. Web. 11 Apr. 2012. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Napoleon_Bonaparte.jpg>.

Daverio, John and Eric Sams. “Schumann, Robert.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online.

Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

De Goya, Francisco y Lucientes. The 2nd of May 1808 in Madrid: the charge of the Mamelukes. 1814. Prado Museum. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 24 May 2007. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Francisco_de_Goya_y_Lucientes_026.jpg

>.

Duffy’s Tavern 118 Eps. Internet Archive. Internet Archive, n.d. Web. 27 Aug. 2012.

<http://archive.org/details/DuffysTavern_524>.

Eroica. Dir. Simon Cellan Jones. Prod. Liza Marshall. BBC, 2003. YouTube. 2 Feb. 2011.

Web. 28 Apr. 2012. <http://youtu.be/M3PzPKD5ACA>.

Franck (De Villecholle, François-Marie-Louis-Alexandre Gobinet). Hector Berlioz. Ca.1855.

Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 11 Aug. 2011. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:151_Franck_Hector_Berlioz.JPG>.

Franklin, Peter. “Mahler, Gustav.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Web. 27 Apr.

2012.

“Franz Liszt.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition.

Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 27 Apr. 2012.

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/343394/Franz-Liszt>.

Frolova-Walker, Marina. “Mussorgsky, Modest Petrovich.” The Oxford Companion to Music.

Ed. Alison Latham. Oxford Music Online. Web. 28 Apr. 2012.

Gibbs, Christopher H. “Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 in E Flat Major, Op. 55.” NPR Music.

NPR. 7 June 2006. Web. 1 Sept. 2016.

<http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5456722>.

“Giuseppe Verdi.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 29 Apr. 2012.

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/625922/Giuseppe- Verdi/215474/Late-years>.

Gran Teatro La Fenice. Rigoletto. 1851. Poster. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 21 Apr. 2012. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rigoletto_premiere_poster.jpg>.

Hamilton, Kenneth. “Liszt, Franz.” The Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham.

Oxford Music Online. Web. 21 Apr. 2012.

Hanfstaengl, Franz Seraph. Richard Wagner, Munich. 1871. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 7 Feb. 2005. Web. 27 Aug. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RichardWagner.jpg>.

“harmony.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition.

Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 20 Apr. 2012.

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/255575/harmony>.

“Harmony.” Exploring the World of Music. Prod. Pacific Street Films and the Educational Film Center, 1999. Annenberg Learner. Web. 29 Aug. 2012.

<http://www.learner.org/resources/series105.html>.

Haydn, Joseph. Symphony No. 94 in G major “Surprise.” 1791. Cond. Neeme Järvi. Perf.

Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. YouTube. 11 Sept. 2011. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/Cbf6lns3i2E>.

Hornemann, Christian. Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven. 1803. Beethoven-Haus, Bonn.

Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 3 Nov. 2007. Web. 27 Aug. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beethoven_Hornemann.jpg>.

Kennedy, Michael. “Mahler, Gustav.” The Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham.

Oxford Music Online. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Kerman, Joseph, et al. “Beethoven, Ludwig van.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online.

Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Liszt, Franz. Appassionata, Etude for Piano in F Minor (Transcendental Etude No. 10), S.

139/10. 1851. Perf. splico17. YouTube. 5 Apr. 2008. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/82Xp0XEIKmQ>.

—. Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 in C minor, S. 244. 1847. Perf. Lang Lang. YouTube. 10 Sept.

2011. Web. 17 July 2016. <https://youtu.be/jYO9gTmCJTE>.

—. Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 in C minor, S. 244. 1847. Perf. Lang Lang. YouTube. 10 Sept.

2011. Web. 17 July 2016. <https://youtu.be/jYO9gTmCJTE>.

—. Liszt Piano Concerto No 3 E flat major Op posth Louis Lortie Charles Dutoit. YouTube. 9 March. 2018. Web. 12 June 2019. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m6iejmSVz_s>

—. Piano Concerto No. 3 in E Flat Major. 1839. Perf. Louis Lortie and the Montreal Orchestra. Cond. Charles Dutoit. YouTube. 21 Feb. 2014. Web. 17 July 20116.

<https://youtu.be/pqN_XB1kVHo>.

—. Tiffany Poon – Liszt Transcendental Etude No.10. YouTube. 5 June 2017. Web. 12 June 2019. < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-fN8_YK1GI>

— . Valentina Lisitsa plays Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2. on YouTube. 19 April 2019. Charles Dutoit.

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LdH1hSWGFGU>

“Ludwig van Beethoven.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://www.britannica.com/biography/Ludwig-van-Beethoven>.

Mahler, Gustav. “Nun will die Sonn’ so hell aufgeh’n.” Kindertotenlieder. 1901. Perf. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Berliner Philharmoniker. Cond. Karl Böhm. 1964. YouTube. 27 Jan. 2012. Web. 29 Aug. 2012. <http://youtu.be/6O8Jn-Uk56k>.

“Mahler, Gustav.” The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. rev. Ed. Michael Kennedy. Oxford Music Online. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Man wearing headphones and seated in front of a computer, used with permission from Microsoft. “Images.” Office. Web. 4 Sept. 2012. <http://office.microsoft.com/en- us/images/results.aspx?qu=listening%20to%20headphones&ctt=1#ai:MP9004225 41|mt:2|>.

Minnesota Public Radio. “Classical Music Playlist: Program Highlights.” Classical Minnesota Public Radio. Minnesota Public Radio, 2012. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

<http://minnesota.publicradio.org/radio/services/cms/pieces_played/>.

Mirsky, Steve. “Perfect Pitch Related to Language.” Scientific American. 21 May 2009. Web.

25 Apr. 2012.

<http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode.cfm?id=perfect-pitch-related- to-language-09-05-21>.

Mussorgsky, Modest. “Promenade.” Pictures at an Exhibition. 1874. Cond. Simon Denis Rattle. Perf. Berliner Philharmoniker. 2008. Music Online: Classical Music Library. Alexander Street Press. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/music- performing-arts/view/work/1533068>.

“Mussorgsky, Modest.” The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. rev. Ed. Michael Kennedy.

Oxford Music Online. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Nadar, Felix. Louis Pasteur. 1878. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 10 Oct.

2010. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Louis_Pasteur.jpg>.

Norris, Geoffrey and Marina Frolova-Walker. “Tchaikovsky [Chaykovsky], Pyotr Il′yich.” The

Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham. Oxford Music Online. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Orr, N. “Richard March Hoe’s Printing Press—Six Cylinder Design.” 1864. History of the Processes of Manufacture. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 23 Sept. 2007. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hoe%27s_six- cylinder_press.png>.

Parker, Roger. “Verdi, Giuseppe.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Web. 20 Apr.

2012.

—. “Verdi, Giuseppe (Fortunino Francesco).” The Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham. Oxford Music Online. Web. 22 Apr. 2012.

Prevot, Dominique. Ludwig van Beethoven’s Website. Dominique Prevot, 2012. Web. 27 Aug. 2012. <http://www.lvbeethoven.com/index.html>.

Raptus Association for Music Appreciation. Ludwig van Beethoven: the Magnificent Master.

Raptus Association for Music Appreciation, 2011. Web. 27 Aug. 2012.

<http://raptusassociation.org/index.html>.

“Richard Wagner.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 20 Apr. 2012.

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/633925/Richard-Wagner>.

“Romantic(ism).” The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. rev. Ed. Michael Kennedy. Oxford Music Online. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Roland John Wiley. “Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il′yich.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online.

Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Samson, Jim. “Romanticism.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Web. 29 Apr. 2012. Schubert, Franz. “Der Erlkönig.” 1815. Perf. Daniel Washington. YouTube. 30 Aug. 2010.

Web. 1 Apr. 2012. <http://youtu.be/oLpsF4uwEVg>.

Schumann, Robert. “Papillons“ and “Pierrot.” Carnaval, Op. 9. 1835. Perf. Yuri Egorov. 2001.

Music Online: Classical Music Library. Alexander Street Press. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/music- performing-arts/view/work/956408>.

—. “Scherzo (Lebhaft).” Symphony No. 4, Op 120. 1841. Cond. Marek Janowski. Perf. Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. 1993. Music Online: Classical Music Library.

Alexander Street Press. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/music- performing-arts/view/work/179728>.

Stieler, Joseph Karl. Beethoven with the Manuscript of the Missa Solemnis. 1820.

Beethoven-Haus, Bonn. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 15 Dec. 2010. Web. 11 Apr. 2012. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Beethoven.jpg>.

Strauss, Johann II. “Overture.” Die Fledermaus. 1874. Cond. Kurt Redel. Perf. Luxembourg Radio Symphony Orchestra. 2009. Music Online: Classical Music Library. Alexander Street Press. Web. 21 Oct. 2014.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/2 000083>.

Taruskin, Richard. “Nationalism.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Web. 20 Apr.

2012.

Tchaikovsky, Pyotr. “Miniature Overture.” The Nutcracker. 1892. Cond. André Previn. Perf.

London Symphony Orchestra. 2007. Music Online: Classical Music Library. Alexander Street Press. Web. 21 Oct. 2014.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/1 705500>.

“Tchaikovsky, Pyotr.” The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. rev. Ed. Michael Kennedy.

Oxford Music Online. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

Thayer, A.W. Thayer’s Life of Beethoven. Ed. Elliot Forbes. Rev. ed. 2 vols. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1967.

Tyranov, Alexey. Girl with Tambourine. 1836. Oil on canvas. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 1 Mar. 2011. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alexey_Tyranov_-

_Girl_with_tambourine.jpg>.

Urban. “Expédition Lewis and Clark.” 31 Dec. 2005. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 21 Aug. 2009. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carte_Lewis-Clark_Expedition.png>.

Verdi, Giuseppi. “La donna è mobile.” Rigoletto. 1851. Perf. Luciano Pavarotti. Dir. Jean- Pierre Ponnelle. YouTube. 11 Apr. 2006. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/8A3zetSuYRg>.

—. “La donna è mobile, the Duke’s aria from Rigoletto.” The Aria Database. Trans. Randy Garrou. Ed. Robert Glaubitz. 2010. Web. 28 Aug. 2012. <http://www.aria- database.com/translations/rig15_donna.txt>.

“Verdi, Giuseppe.” The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. rev. Ed. Michael Kennedy. Oxford Music Online. Web. 29 Apr. 2012.

—. Va. Pensiero (Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves) – Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco – Kendlinger. YouTube. 7 September 2014. Web. 19 April 2019.

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XttF0vg0MGo>

W. & D. Downey, Photographers. Franz Liszt. Ca. 1880. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons.

Wikipedia Foundation, 23 Apr. 2012. Web. 27 Aug. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Franz_Liszt_1880s.jpg>.

Wagner, Richard. Die Meistersinger Overture, WWV 96. 1862. Cond. Herbert von Karajan.

Perf. Berliner Philharmoniker. 2004. Music Online: Classical Music Library. Alexander Street Press. Web. 27 Aug. 2012.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/music- performing-arts/view/work/1475142>.

“Wagner, Richard.” The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. rev. Ed. Michael Kennedy.

Oxford Music Online. Web. 22 Apr. 2012.

Wagner, Richard. The Ride of the Valkyries from Wagner’s Ring Cycle at the Met. 1854. Perf. New York Metropolitan Opera. Deutsche Grammophon. YouTube. 3 Sept. 2012. Web. 17 July 2016. <https://youtu.be/xeRwBiu4wfQ>.

Walker, Alan, et al. “Liszt, Franz.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Web. 29 Apr.

2012.

Wallmüller. Leipzig Apernhaus, Aufführung der ‘Meistersinger.’ 1960. Photograph. German Federal Archives. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 4 Dec. 2008. Web. 27 Apr. 2012. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-

76973-

0002,_Leipzig,_Opernhaus,_Auff%C3%BChrung_der_%22Meistersinger%22.jpg>.

Warrack, John. “Romanticism.” The Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham. Oxford Music Online. Web. 22 Apr. 2012.