2 Chapter 2

Early Western Art Music

By David Whitehouse

Figure 2.1 Phintias, Music Lesson, ca. 510 BCE. The teacher is on the right, the student on the left. Between them a boy reads from a text.

MEDIEVAL OR (Middle Ages)

The Western music known today has its roots in the musical practices found in Europe and the Middle East over twenty centuries ago. These musical practices, in turn, have their roots in ancient Greek and Roman practices which are detailed in musical and philosophical treatises of the time. Greek civilization, with its political structures, its architectural and musical attainments, and its great achievements in philosophy and poetry, has influenced European culture and in turn American culture.

Music from these two ancient civilizations cannot be heard or faithfully reconstructed because the historical records are sparse and incomplete. The Greeks produced a rich trove of writings about music. What is known of the Greek practices of music come from philosophical works such as Plato’s Republic, Aristotle’s Politics, and from thinkers such as Pythagoras. Pythagoras was the first to note the relationship of the intervals of music to mathematics. Greek writers thought that music influenced morals, and was a reflection of the order found in the universe. Over the long period of Greek civilization, many writers emerged with differing viewpoints.

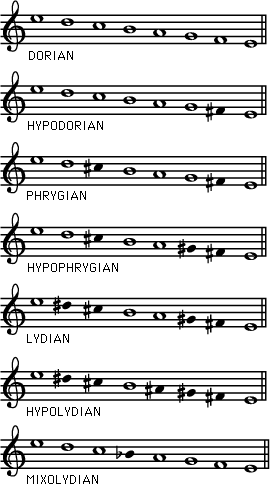

These viewpoints include the relationship of musical rhythm to poetic rhythm. They delineate precise definitions of melody, intervals, scales, and modes. This last term, mode, means the relationship of notes in a scale. Much of Western Art Music uses the two modes called major and minor. The Greeks had several further modes which reflected the practices of the time. These ideas, while forgotten and disused after the ascendance of Roman dominance, were nevertheless rediscovered in later centuries and formed the basis of musical practice. Listen to a recreation of the oldest known complete song from Greek civilization called, “Song of Seikilos.” Please note that for this chapter, transcripts of song and music lyrics are not necessary to gain an understanding of the material.

Figure 2.2 Seven Greek modes in modern notation showing the whole and half-step patterns which characterize each. The modes shown are Dorian, Hypodorian, Phrygian, Hypophrygian, Lydian, Hypolydian, and Mixolydian.

Less is known of Roman music. After the Greek islands became a Roman province in 146 BCE, music played an important function at festivals, state occasions, religious rites, and in warfare. Writers of the time tell of large gatherings of musicians and of music competitions, and depict choruses and orchestras. Emperors improved their image by funding music and other arts. However, Roman musical practices had no direct bearing on the development of European culture.

After the fall of Rome, generally ascribed to the year 476 CE, civilization in this part of the world entered the “Middle Ages”. Extending for a thousand years, the first five hundred years of the Middle Ages has until recently been described as the “Dark Ages” or the Gothic Period. These years were actually a time of the coalescing of societal forces that serve as the basis of our understanding of music, art, architecture, literature, and politics. The Church developed its liturgy and codified the music it used. Visual art moved toward expressions of realism—the attempt to depict subjects as they appear objectively, without interpretation.

(SACRED MUSIC)

Literature developed and language was becoming standardized in many countries. Kings and noblemen began sharing power with the authorities of the Church. Politics was in a nascent stage with the advent of barons of commerce who, with their control of resources and trade, formed guilds. All of these developments had consequences for the development of music.

Gregorian Chant and the Liturgy

As the Church spread over the continent of Europe the basic shape of its worship services formed. In the monasteries that were founded, the monks and nuns lived their lives around a daily rendering of worship in the church. There were, and are still, eight of these worship services called offices, and a ninth chief service called the Mass. All services had as their basis readings from the Bible, weekly recitation of the Psalms, and regular prayers.

Over time these texts were sung, rather than simply recited. This singing was most likely an outgrowth of the society in which early Christians found themselves, with influences from Jewish, Hebrew, and Middle Eastern cultures. Scholars debate how the melodies for these texts, referred to as Gregorian chant, plainsong, or plainchant, came into being. All three of these terms refer to the same thing.

Monophonic texture, also called monophony, involves only one melody with no harmony. Gregorian Chant-written music example video (Monophony)

They are called plain because their chief characteristic is a one line

melody, called monophony, described by the term monophonic. Many hundreds of these melodies developed by the middle of the sixth century. They can be classified as sacred as opposed to secular.

The idea of adding some additional texture under these melodies evolved later in music with:

Homophonic texture, also called homophony, involving one clear melody with harmony or background material. Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus (Homophony)

Figure 2.3 Sadler, Joseph Ignatz. Saint Gregory the Great, eighteenth century. In this fresco from a church in the Czech Republic, Pope Saint Gregory the Great is shown receiving inspiration from a dove, the representation of the Holy Spirit of the Christian church. This is an inspiring if apocryphal story.

Pope Gregory the Great (who held papacy from 590 to 604 CE) began the process of collecting and codifying these chants in order to bring stability to what was allowed in the services; thus they acquired the name Gregorian. Many plainchants in the same style came into use after the time of St. Gregory. The schola cantorum that Gregory founded trained singers in this body of chant and sent them to teach it in disparate lands. Later, Pope Stephen II and French kings Pepin the Short and Charlemagne also encouraged the spreading of these chants to a much wider area, at some times by force.

Monophony in the chant was aided by other characteristics, including free flow of the melody with no perceivable rhythm. Cadences, musical sequences that provide resolution to phrases, occurred at advantageous points in the text to add an understanding of what was being sung; introductory and ending notes provided starting and ending points. Chanting, i.e. the singing of words, provides a heightened sense of the text’s importance, and an understanding that is not as readily available when speaking the text. Church leaders deemed it appropriate to the intent of the worship services to have the texts, which were entirely in Latin, sung and not merely spoken.

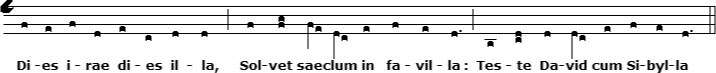

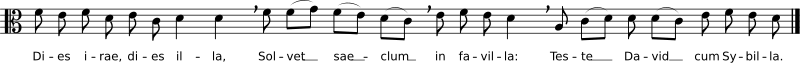

An example of one of the most famous of these chants is called “Dies Irae”, or “Day of Wrath”.

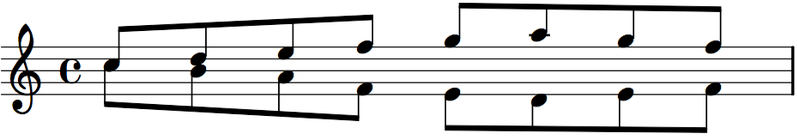

Figure 2.4 This image shows the Gregorian “Dies Irae” chant with Medieval notation, referred to as neumes. The complete chant is over 6 minutes long. Ctrl+click on the image and select audio file 02 Track 2 to listen to the chant.

Figure 2.5 This image shows the Gregorian Chant “Dies Irae” in modern notation. .Ctrl+click on the image and select audio file 02 Track 2 to listen to the chant.

In listening to the chant, it helps to remove any distractions that modern life has given us; chants were sung in formal worship with nothing else going on, except the actions of the clergy in the services. “Dies Irae” is a text that was sung during a special version of the Mass called a Requiem Mass, or Mass of the Dead. It depicts what was extant in theology of the time: the day of wrath and mourning when the soul is judged. The chant reveals the typical progression of plainchant, with nuanced melodic contours inspired by the text itself. There is no foot-tapping rhythm. Each phrase of text is marked by longer notes, starting and ending as if from the ether. This chant will reappear several hundreds of years later when it is used by Hector Berlioz in his Symphonie Fantastique in the early nineteenth century.

By the time Gregory was working, ca. 600 CE, many chants were in use and a system of notation had developed for accurate learning and rendition. Shown above are “Dies Irae” two examples of the same music; the first is the music as it appeared in the Middle Ages, the second is a modern notation.

As you listen notice the main characteristics of the music: 1. there is no strict rhythm—the music flows in a gentle manner with no beat; 2. the words are set almost always one syllable to a note but some syllables have more than a few notes, called melisma; 3. there is no accompaniment or other voice—this is strictly a one-line melodic progression of notes referred to earlier called monophony.

Secular Music

Music outside of churches in the Middle Ages was not written down. Music in societies where the majority of the population was non-literate was passed down orally, and this music has been almost entirely lost. Known to us are wandering minstrels who were the professional musicians of their day. They would provide music for tournaments, feasts, weddings, hunts, and almost any gathering of the day. Minstrels performed plays, and they would also carry with them news of surrounding areas. Often they would be employed by lords of the manors that made up medieval society. Troubadours (feminine trobairitz) were active in the south of France, trouviers in the north. In German lands the same type of musicians were referred to as minnesingers.

Music outside of churches in the Middle Ages was not written down. Music in societies where the majority of the population was non-literate was passed down orally, and this music has been almost entirely lost. Known to us are wandering minstrels who were the professional musicians of their day. They would provide music for tournaments, feasts, weddings, hunts, and almost any gathering of the day. Minstrels performed plays, and they would also carry with them news of surrounding areas. Often they would be employed by lords of the manors that made up medieval society. Troubadours (feminine trobairitz) were active in the south of France, trouviers in the north. In German lands the same type of musicians were referred to as minnesingers.

Figure 2.6 These two troubadours play stringed instruments, one strummed and one bowed; Figure

- The troubadour calling is alive in modern times.

Texts of these musicians often revolved around human love, especially unrequited love. The exploits of knights, the virtues of the ruling class, and the glories of nature were among other themes. The musicians most often composed their own poetry.

These songs were accompanied by instruments such as the vielle, the hurdy-gurdy (for the remainder of the links in this section, click the image on the web page to hear an example), and the psaltery.

Figure 2.8 This is a modern reproduction of a Medieval fiddle or vielle which is played with a bow. Figure 2.9 This woman is playing a psaltery shown held in her lap and bowed.

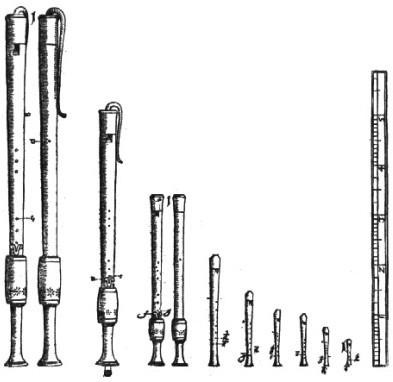

Rhythm instruments such as the side drum and the tabor (usually played by one person with the pipe) provided rhythmic underpinnings. Other Medieval instruments include the recorder and transverse flute, the shawm, the bladder pipe, the serpent, and the lizard.

Figure 2.10 This image shows several sizes of the Renaissance recorder. Figure 2.11 From left to right: shawm, Baroque oboe, modern oboe.

The Beginnings of Polyphony

From the single-line chanting of the monks and nuns, music gradually came to be polyphonic, meaning more than one line of music playing simultaneously. The simplest form of adding another voice is to use a device called a drone. (similiar to the black hole sound we heard last week). This is a note or notes that are held while the melody plays. This musical arrangement is found in many European and Asian cultures in their folk music, suggesting a long history.

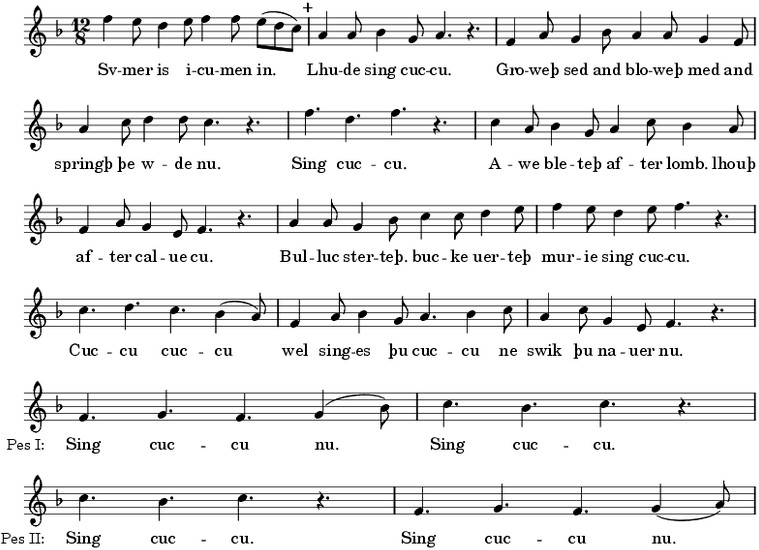

Ex: “Sumer Is Icumen In” In round form.

Our example of “Columba Aspexit” (“The dove peered in”—for interested students, a translation of the lyrics can be accessed at the Columbia History of Music website) composed by Hildegard of Bingen shows the

amazing complexity that the vocal lines achieve while still relating to the background drone.

Another device used in oral traditions in the Church was organum. Organum is the singing of chant with another voice singing exactly the same chant only at differing intervals (an interval being the difference in pitch between two notes). The second voice follows the chant in exact parallel motion. In the ninth century the fifth (notes at the interval of five steps) was considered a perfect interval, pleasing and harmonious. Therefore the movement of the two voices, while it may sound dry and uninteresting to the modern ear, was pleasing and reassuring to medieval listeners.

Music moving along in parallel fifths was not the only way organum was practiced. In order to avoid certain intervals while the chant progressed, the singers of the accompanying voice had to alter certain notes, move in contrary motion, or stay on the same note until the chant moved past the note that would have created a forbidden interval. For example, the tritone (an interval of two notes with six half steps or semitones between them) was considered an unstable, dangerous interval. It was said to personify the devil and was avoided in sacred music—and in some cases specifically forbidden under Canon law.

Changing the chant to avoid certain intervals such as the tritone provided the beginning of oblique and contrary motion. This development led the way to thinking of music as a combination of voices rather than a single line. Polyphony can be said to have arisen from this practice.

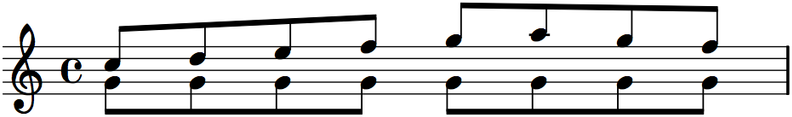

Figure 2.12 This music shows oblique motion where one voice remains on the same note.

Figure 2.13 This music shows the two voices moving in opposite direction called contrary motion.

How did this come about? It is good to place ourselves in the context of plainchant music creation in order to understand the genesis. As stated earlier, debate continues over exactly when these practices began, but they most likely have their roots in the Byzantine, Hebrew, and Jewish chants in which Christianity itself has its roots. Gregory’s attempt to

codify and restrict music in the Church was circumvented by the process of singing dozens of chants and lengthy texts nine times a day, 365 days a year. The chants were passed down orally. New monks and nuns would learn the chanting by rehearsing and singing the nine services. Chants were sung from memory. As the Mass was the chief service of the church, it was performed with increasing ritual, ornamentation, and pageantry. Music also became more complex. The addition of a second voice singing at the fifth (or fourth) would have enriched the resonance in the large acoustic spaces of the monasteries and cathedrals that began construction in the Medieval era. The addition of polyphony took place gradually over long periods of time so that each succeeding generation would accept and enlarge upon concepts they automatically learned when entering into a religious order.

From the auspicious beginnings of organum (parallel, oblique, and contrary motion of the chants with one added voice), new styles developed. One of the most important places of further development came in Paris at Notre Dame Cathedral. Reflecting the magnificence of the building, the rich stained glass windows, and the ornate style of decorative stone, the music developed in proportion and complexity. Two significant practitioners emerged from

this place and time: Leoninus (or Leonin, active ca. 1150-1201) and Perotinus (or Perotin, active late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries).

this place and time: Leoninus (or Leonin, active ca. 1150-1201) and Perotinus (or Perotin, active late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries).

These two musicians were part of a tradition of musical practice that might be called “collective composition.” This means that the musical performance of orally transmitted chant

Figure 2.14 Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris is shown from across the Seine river.

acquired variations, with each musician writing down their own musical preferences. This style of music has as its basis the chants of the Church. The chant was sung to long, sustained pitches while another melody was sung above it. The chant melody, the tenor, becomes like a drone in this music because of the length of each note. The melody which flows along on top of each note of the tenor, called the duplum, had many notes to each note of the tenor. Much subtlety of rhythm and the beginnings of form are contained in these versions of the chants. Leoninus is credited with first composing organa (plural of organum) that had more than a few notes in the duplum to each note of the chant. This enrichment of the chant itself may have been inspired by the magnificence of Notre Dame Cathedral, and provided further enrichment of the most important liturgy of the church, the Mass.

Perotinus extended and developed even further the advances notated by Leoninus. Above the chant, he added more than a single voice. He composed chant with one, two, and three voices accompanying it. Chant with one voice added is called organum duplum, with two voices added, organum triplum (triplum for short), and with three voices added, quadruplum. Perotinus’ music achieved a complexity of texture, rhythm, and harmonic implication that resonated throughout the known Christian world. Our example is two separate settings of the opening of the chant “Viderunt Omnes.” The first setting, sung by the Choir of the Monks of the Benedictine Abbey of St. Martin, Beuron is monophonic—a single line, sung with all voices on the same note. The second setting is polyphonic, with four different voices performing different lines simultaneously (ctrl+click on the image to listen to this example).

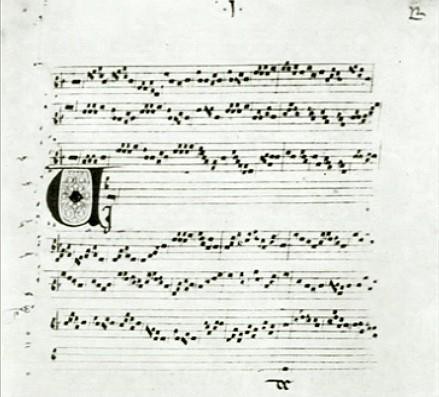

Ex: Neumes – (square notes & various symbols written on a music staff)

Figure 2.15 Perotinus, “Viderunt Omnes,” ca. 1200. This image shows the polyphonic chant, with four melodic lines singing simultaneously. The large “V” is from the first word, “Viderunt”. Ctrl+click the image to hear an example of this chant.

The chanters sing an opening pitch together. Listen to how the lowest part keeps singing as the upper parts take a breath and begin long melismas above the drone-like note of the lower part (as a reminder, melismas are simply multiple notes sung to one syllable of text). The lower part is actually singing the chant melody, but now in lengthy, drawn-out notes. The flexibility of rhythms and the interplay of the upper voices, imitating each other and crossing lines, influenced music-making in the wider culture.

Motet

In addition to setting liturgical texts with the added voices of duplum, triplum, and quadruplum, musicians at this time began using other Latin texts, some newly written, with

the added vocal parts. This resulted in a new way of thinking about what type of texts would be used with the new musical style. Chant was the official music of the Church, and sacred composers were seeking new ways of expressing the developments of society at the time. They were also aware that the Church authorities were using different tactics to mark the Mass as the most significant service of the church. New architectural grandeur, highly stylized clerical attire, ornate decorations of wood and stone, and the growing complexity of chant practices all reflected the significance of the Mass. While retaining the official chant, composers were responding to a concomitant blend of richness and complexity all around them.

The addition of voices to a chant—and the idea of setting new words to those voices— resulted in the motet. The words used were fit for various occasions: regular services of the church, special days such as Christmas and Easter, and special local circumstances, such as the founding anniversary of a church or the crowning of a monarch. Eventually, other subjects were used for the accompanying voices, including love poems. The liturgical chants on which they were layered also came to be optional, with the composer either writing a new chant or adapting an existing one rhythmically.

Mention must be made here of a special type of polyphonic work called the round. “Sumer Is Icumen In” is a round that was written sometime after 1250 by an anonymous composer. It is for four voices singing one after the other in continuous fashion, with two more voices in the background repeating “sing cuckoo” repeatedly. The text praises the coming of summer. The tone is bright and happy. The two background voices are called the pes, Latin for “foot”.

Figure 2.16 “Sumer Is Icumen In”, a 13th century round, is shown in modern notation. The bottom two lines, Pes I and II, are sung as background. New voices enter from the beginning at +. Ctrl+click on image to listen to an example.

As the 1300s began, polyphony became increasingly complex. Rhythm became a predominant feature of a new style of composing called Ars Nova. This “new art” was characterized by greater rhythmic variety, melodies that were longer and more shapely, and increasing independence of individual lines of music.

Ways of writing music developed that showed division of longer notes into shorter values (breve, to semibreve, to its smallest division, the minim). The use of a device called isorhythm (“equal rhythm”) came into more complex practice with the motets of Philippe de Vitry (1291-1361). This extended practices found at Notre Dame and in earlier motets, increasing the rhythmic complexity and extending the melodic pattern of lines. For an example of isorhythm’s use, listen to Vitry’s “Vos Qui Admiramini/Gratissima Virginis/Gaude

Gloriosa”.

While listening to the interweaving melodies, notice recurring rhythmic patterns occurring within longer melodic segments. These may or may not coincide, sometimes

beginning together, sometimes overlapping, and not always ending together. Also notice that the melodic range—the distance between the melody’s lowest and highest notes—is wider than previously encountered in the earlier Medieval period (compare the relative closeness of the intervals of Perotinus’ “Viderunt Omnes” or the stepwise motion of the “Dies Irae” chant). The lower two voices have longer rhythmic units of their own and provide a sonic backdrop to the upper parts.

Listening Objectives

Listening objectives during this unit are to:

- Listen for fluidity in the melody of Gregorian chant. Listen for the lack of rhythmic beat.

- Listen to early examples of polyphony including:

- instrumental drone with human voices;

- human voices singing in parallel fifths no instruments; and

- human voices singing long drone notes (which are notes of the chant) while other human voices sing in and around each other along with the drone notes.

- Listen for differences in energy and mood between sacred and secular music.

- Listen for how instruments are used both in conjunction with human voices and independently.

Key Music Terms

Instrumentation The Renaissance (ca. 1400-1600) was a time of developing

SATB: The human voice was considered the prime musical instrument, and all other instruments strove to emulate its expressive capability. Humans

SATB: The human voice was considered the prime musical instrument, and all other instruments strove to emulate its expressive capability. Humans

have four general ranges of singing: the higher soprano and lower alto for women, and the higher tenor and lower bass for men. (SATB) Instruments developed in ways that corresponded to these designations. These are called families of instruments, such as the viol family.

Keyboard instruments also developed highs and lows by simply extending the keyboard; the harpsichord and organ became the principal Renaissance keyboard instruments.

Instruments are classified by how they are played. Strings are bowed and plucked, woodwinds are blown with reeds and varying mouthpieces to produce sound, and brass instruments are blown with lips against a rounded mouthpiece. In this period, designations were rarely given for the musical part that would be played by a specific instrument. Can you name instruments from each of these classes from the Renaissance?

Timbre or Tone Quality The sound of Renaissance instruments is “thin” to our ears.

Timbre or Tone Quality The sound of Renaissance instruments is “thin” to our ears.

Details of design and materials of construction gave limited results. The preferred timbre of human voices can only be guessed at because there are no recordings, methods of vocal production were different, and the sound of vowels and other elements of local languages for which music was written are unknown. “Haut” and “bois” were terms used for instruments suited for outdoors (haut/high) and for indoors (bois/low). In this case, high and low refer to the strength of the tone.

Texture Textures varied from solo instruments such as the lute, harpsichord, and organ, to massed choirs with brass and other instrumental accompaniment. During

Texture Textures varied from solo instruments such as the lute, harpsichord, and organ, to massed choirs with brass and other instrumental accompaniment. During

the Renaissance, accompaniment referred to doubling the human voices with the instruments, not playing an independent instrumental accompaniment. Texture in the Renaissance had a solemn, other-worldly quality, especially in sacred music. Secular music generally sounds thin, as opposed to resonant, and does not carry far.

Harmony During the Renaissance, harmony moved in blockish groups. Individual lines of music moved with each other to produce modal effects. Not until the

Harmony During the Renaissance, harmony moved in blockish groups. Individual lines of music moved with each other to produce modal effects. Not until the

Baroque Era did each line of music became equally important, relating to the other lines of music in rhythmic collusion toward tighter harmonic schemes. All modes were still used in the Renaissance. These gradually gave way to only two modes, major and minor, by the end of the Baroque Era.

Tempo Tempos (tempi) in the years preceding the Baroque Era were generally slower. Sixteenth notes were not unheard of, especially for solo lute and keyboard

Tempo Tempos (tempi) in the years preceding the Baroque Era were generally slower. Sixteenth notes were not unheard of, especially for solo lute and keyboard

pieces, but were unusual for chorus and ensemble writing.

Dynamics Dynamics were generally not designated during the Renaissance.

Dynamics Dynamics were generally not designated during the Renaissance.

Because music written at this time was not created for wide dissemination, the composer and those performing it would have known what they preferred in terms of dynamics and thus they were not recorded.

Form Forms were the province of both sacred and secular music in the Renaissance. Popular musicians, called troubadors, trouviers, and minnesingers

Form Forms were the province of both sacred and secular music in the Renaissance. Popular musicians, called troubadors, trouviers, and minnesingers

among others, sang popular songs such as the villancico (a song style used in the Iberian peninsula) and frottola (a popular Italian secular song), with the most enduring of all being the Italian madrigal. Sacred music included forms such as the motet and the sections of the Mass (kyrie, gloria, sanctus, credo, and agnus dei), and forms that grew out of other parts of the divine service.

The Renaissance

The Renaissance is a designation that historians have used to cover the period of roughly 1400 to 1600, although the exact dates have been debated. Every historical period must be seen in the light of ongoing developments in all aspects of society; the Renaissance is no exception. While composers, performers, theorists, makers of musical instruments, sculptors, painters, writers of all types, philosophers, scientists, and merchants were all making advances, they were not doing so in sudden, entirely new ways. “Renaissance” is a term meaning “rebirth,” which implies that things were born anew, with no regard to what had come before. In the case of the Renaissance, this not precisely accurate. The rebirth that is suggested is the rediscovery of Greek and Roman civilization—their treatises and philosophies, their ways of governing. In actuality, leading figures of the time took ideas from the Greek and Roman civilizations and applied them to contemporary currents of thought and practice. Renaissance people had no desire to rid themselves of their religion. They rather had the desire to elevate their faith in reason and in the abilities of humans alongside their faith in the divine.

The art of music was influenced by many historical and artistic advances during this period, including the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the invention of printing and paper around the year 1440, Michelangelo’s way of depicting the human form as in his statue of David and in his painting of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and the writings of Michel de Montaigne, Miguel de Cervantes, and Dante Alighieri. In music, the practices of old continued and were updated, while international styles were being cross-bred by musicians travelling and mixing local practices. Late in the fifteenth century two characteristics of music emerged and came to predominate. Imitative counterpoint (when two voices repeat a specific melodic element) and homophony (when two or more parts move in the same

rhythm and in harmony) are found in much music composed and performed in the Renaissance.

Printed music was developed by 1501 and made dissemination and availability much wider. Styles were no longer confined to one particular place with little chance of reaching a wider populace. Printing music made written music less expensive, as less labor was involved and printed music became in demand from humbler households during the sixteenth century. The increasing relative wealth of the average person now allowed for access to printed scores, instruments on which to play those scores, and the time to enjoy them.

Upheavals in the Church affected music in diverse ways. The Protestant Reformation began when Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg in the year 1517. As other countries saw reactions against the authority and profligacy of the Catholic Church, the Church launched its own counteroffensive in what is called the Counter Reformation. The Council of Trent was held intermittently for a very long period, from 1545-63. Discussion concerning the purification of music that was allowed in church services took place during this Council. There was talk of purging the services of any polyphonic music, primarily because the words had become difficult to hear. A legend arose surrounding an acknowledged master of high Renaissance polyphony, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525/1526-94). According to the legend, Palestrina wrote the “Missa Papae Marcelli” (“Pope Marcellus Mass”) to argue for keeping polyphony in the Church.

Palestrina was in service to church music almost his entire life, spending over forty years in churches in Rome. He became renowned especially for his Masses and motets. For an example, listen to a section from the legendary “Mass for Pope Marcellus.”

The “Gloria” is one of the five sections of the Mass. In this music, one can hear a many-layered texture. Beginning with jubilation, the voices sing in rhythmic equality. The mood is at times solemn, and the effect is serene. The tone is one of humility yet grandeur, a fascinating combination of the attitude that the worshiper was encouraged to have when

approaching the divine in liturgy. The listener senses the importance of the words, yet is never bogged down. There is regular pulse, yet the feeling of meter is just out of reach. The music flows in stepwise fashion for the most part. There are regular cadences that conform to the phrases of the text.

Palestrina holds a distinct place in sacred music of the Renaissance, but what of the music-making at court and in the countryside? Two main developments during the Renaissance are the madrigal and secular song.

Printing music made written music less expensive, as less labor was involved.

Formerly the province of rich households, the nobility, and those working with the resources of the Church, printed music became in demand from humbler households during the sixteenth century. Types of popular song became widespread in composition and use—in Spain, the villancico, in Italy, the frottola, and in other styles in other countries. Most enduring of all popular music at this time, however, is the Italian madrigal. All popular music sought to express varieties of emotion, imagery, and specific themes, and to experiment with declamation, expressing character and drama.

The Italian madrigal reigned supreme in its achievements in these areas. Poetry of various types was set to through-composed music. Through-composed refers to a style of composition where new music is used for each line of poetry. In the first half of the 1500s, most madrigals were composed for four voices; later five became the norm, with six not unheard of. Composers sought to express the themes of the poems, individual ideas of each line, and even single words. While “voices” here can mean human singers, using instruments on the vocal parts was standard practice, especially if a human to sing the voice part was missing.

One example of the spread of the Italian madrigal style is by Bavarian Orlande de Lassus. Entitled “Eco,” it is a light-hearted take on words that tell of an echo. One can readily hear the effects of the word painting. This is but one of an infinite variety of examples of how madrigals are expressive, contrasting, and imitative, conveying intensity of feeling in an open, robust way.

Italian madrigals foremost, with French chansons and German Lieder (both terms mean “song” in those languages), and English madrigals, set the stage for the birth of opera. Techniques found in madrigals, chansons, and lieder of the time were also found in music used in the presentation of plays. Discussion of these will continue in Chapter 3. Since the majority of this chapter has concerned music for voices, discussion turns now to the instrumental music that preceded the full flowering of the Baroque orchestra.

Renaissance musicians played a variety of instruments. Modern musicians typically specialize in one instrument and possibly closely related ones as well, but it was expected of a musician in this time to be proficient at more than a few. These can be broadly classified into haut (high) and bas (low) instruments—that is, loud and soft. Haut instruments would be suitable for playing outdoors, bas for indoors. Until the end of the sixteenth century, composers did not specify which instruments to use. There were varieties of ensembles, depending upon what was available or working at any given point. Wind instruments include the recorder, transverse flute, shawm, cornett, and trumpet. The sackbut (precursor to the trombone) and the crumhorn (double reed, but still a haut instrument) were additions of the Renaissance. To add percussive effects, the tabor, side drum, kettledrums, cymbals, triangles, and bells were played, though parts for these were not written. (See the discussion of these instruments with examples above.)

The lute gained particular favor, as the modern guitar is favored today. It was a five-

stringed instrument with a pear shape. Leather straps around the neck to tell the player where to place his or her fingers. Great varieties of effect could be produced, with lutenists playing solo, accompanying singing, and playing in groups.

Among the string group of instruments is the viol, or viol da gamba. This is a bowed

instrument which is the precursor to the modern violin. The viol family contains instruments in every range, from soprano as the highest to bass as the lowest. A group of viols playing together was referred to as a consort of viols. The violin was present at this time as a three- stringed instrument used to accompany dancing, tuned in intervals of fifths rather than the fourths of the viol.

Keyboard instruments included the pipe organ, which was growing in size and

complexity. From the portative (small organ that can be carried) and positive organs (larger version of the portative and on wheels) of the Middle Ages came fixed instruments much larger and capable of grander and more varied sound. Germans later added pedals to extend the range and power of the instrument. The clavichord is a small household keyboard instrument in which keys are connected to brass nubs which strike the string, causing it to vibrate. The harpsichord also has keys, but these are connected to a quill which plucks the

string. The harpsichord has a much bolder sound and grew to have two and even three keyboards. It became one of the two most important keyboard instruments in music of the Baroque period, the other being the organ.

Separate Instrumental Music:

What were these instruments playing? As noted, they were added to vocal music to round out and fill in the sound. In time they acquired independent music of their own, with no relation to or reliance upon a composition intended for vocal production. It is important to note that instrumental music was increasingly viewed as independent from vocal music.

While some instrumental music was arranged from pre-existing vocal music, other forms of instrumental music include settings of existing melodies such as chorale melodies of the churches, songs, and dance music. The first instrumental works that had no connection to earlier vocal music appeared at this time. These instrumental works established in the Renaissance include the prelude, fantasia, toccata, ricercar, canzona, sonata, and variation. Variation form was invented in the sixteenth century. It reflected a practice in existence where the musician would vary the music that was presented to him or her in written form. A basic theme could be enhanced by changing the harmony, adding upper or lower notes, using flourishes and runs, and including other devices that inspired the composer or performer.

While some instrumental music was arranged from pre-existing vocal music, other forms of instrumental music include settings of existing melodies such as chorale melodies of the churches, songs, and dance music. The first instrumental works that had no connection to earlier vocal music appeared at this time. These instrumental works established in the Renaissance include the prelude, fantasia, toccata, ricercar, canzona, sonata, and variation. Variation form was invented in the sixteenth century. It reflected a practice in existence where the musician would vary the music that was presented to him or her in written form. A basic theme could be enhanced by changing the harmony, adding upper or lower notes, using flourishes and runs, and including other devices that inspired the composer or performer.

“Renaissance Instrumental Video” – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vxPB76pmWss

“Ricercar” Recorder/Flute Quartet– https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ob8tYRQTQbI

“Toccata” Pipe Organ” – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3MZ1VF8Ver0

“Fantasia” sm.group – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dS4ii1iy9p0

“Sonata” sm.group – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OzVB_BAju3I

“Prelude” ; Lute – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4TGrOuyRLwI

“Mod Canzona”, voice & accom – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TETgHZf6ho0

“ Variations”(Greensleeves): Lutes – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URS3DWZbZjg

“Mod Variations”: Ele.Orch –https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VqS3pkQ665s

Venice now emerges as a principal area of for the arts. Venice was a major urban center in the sixteenth century – a conflux of trade routes, international society, and wealthy patronage. All aspects of society were affected by the immense wealth that predominated. Churches were ornate; the best sculptors, painters, and architects abounded, and musicians were no less affected. St. Mark’s Basilica is a prime example of these

displays of artistic endeavor.Figure 2.17 St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice. This is the view

from the museum towards the altar.

Lavishly ornate, with an altar of gold, huge Byzantine domes, and decoration of every known variety and ornament, St. Mark’s also boasted numerous balconies and spacious acoustics. Performance in this place attained spectacular effects in the music of Giovanni Gabrieli (ca. 1555-1612). For example, Jubilate Deo (Rejoice in the Lord), composed for eight voices, shows several techniques that Gabrieli brought to perfection:

- the use of two vocal choirs of four voices each

- alternating effects of the two choirs

- high voices juxtaposed by low voices

- imitation throughout

- interspersed sections of full choral texture

On a recording there is no way to capture the complete effect of two choirs, sitting across from each other in the vast space of St. Mark’s, singing into the space underneath the resonant main dome of the church. These techniques are not unique to Gabrieli, but he brought them to high achievement.

The Renaissance was a period of re-birthing ancient philosophies (and ancient music) into current life and practices, and of enhancing faith in God and the authority of the Church with faith in human reason and capability. From the organum of Leoninus and Perotinus came the multi-voiced motet and complete settings for the Mass. From the practices of troubadours, trouveres, and minnesingers came the Italian madrigal. From accompanying voices and filling in parts in vocal compositions came the independence of instrumental forms. The stage was now set for the birth of opera, the standardization of the Baroque orchestra, the rewriting of rules of composition to reflect major and minor tonality rather than use of modes, and the creation of forms out of older models.

Closing – Medieval & Renaissance Eras

In this chapter we have seen Western Art Music progress in two distinct areas: sacred and secular. Very broadly speaking, during this period music moved from one-voice monophony to many-voiced polyphony. Monophony began moving toward polyphony with the use of drones and organum. Instituting the use of parallel fifths rather than simply single-line chanting started the process of independent voices moving away from the original monophonic chants. Later all voices moved independently, with none being based on a chant. At first only sacred texts were used for all vocal music; eventually texts came to reflect other themes. This gave rise to new forms of music including the motet. In secular music, instruments were used merely to double voice parts at first, and in time, music was written for instruments alone. The time period of these developments is approximately

1400-1600, and the areas involved are principally in what is referred to in the modern-day as Europe.

The Transformative Power of Music

This week, watch the video “The Transformative Power of Music,” part of the Annenberg Learner video series we will be viewing throughout the text.

Guiding Questions:

Identify, describe, and provide examples of various types of early music.

- How did music move from one-line monophony to many-voiced polyphony?

- How did instruments come to be independent of vocal music?

- What societal developments influenced the composing and writing down of music?

- What were the texts used for these independent voices?

- What forms developed that set the stage for the birth of opera, oratorio, and independent musical forms of the Baroque period?

Self-Check Exercises

Complete the following self-check exercises to verify your mastery of key music terms presented in this chapter.

- What is one-line (one-voice) music called?

- Monophony

- Heterophony

- Polyphony

- Stereophony

- What cathedral and what 2 composers working there are associated with major progress toward many-voiced music?

- Chartres – Leonin/Perotin

- Bordeaux – Hildegard/Bernart de Ventadorn

- Notre Dame – Leonin/Perotin

- Orleans – Adam de la Halle/Philippe de Vitry

- How were instruments used in vocal music from the Renaissance and earlier?

- They filled in for missing human voices.

- They played vocal music when there were no human voices.

- They played when all human voices were present.

- All of the above.

- Of the following, which contain sacred and secular forms of music from this time?

- Sonata, Symphony, Gregorian Chant, Lieder

- Gregorian Chant, Chanson, Mass, Organum, Madrigal, Round

- Concerto, Suite, Organum, Madrigal

- Variations, Rondo, Mass, Frottola

If you would like additional information about these terms, please review before proceeding. After you have read the questions above, check your answers at the bottom of this page.

Self-check quiz answers: 1. a. 2. c. 3. d. 4. b.

Works Consulted

Ball, David. Troubadour. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 28 Feb. 2007. Web. 15 Feb. 2012. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Troubadour-2003.jpg>.

Byrd, William, composer. “William Byrd – Fantasia #2 – Viol Consort.” YouTube, 2 Sep. 2008.

Web. 18 Feb. 2012. <http://youtu.be/w-qS7ms5apQ>.

Construction tools sign, used with permission from Microsoft. “Images.” Office. Web. 4 Sept.

2012. <http://office.microsoft.com/en- us/images/results.aspx?ex=2&qu=tools#ai:MC900432556|mt:0|>.

Couperin, François, composer. “Harpsichord – Bridget Cunningham plays Les Baricades MisterieusesCouperin.” Perf. Bridget Cunningham. YouTube, 14 Feb. 2009. Web. 28 July 2012. <http://youtu.be/Z-LV4_mem6Q>.

De Lassus, Orlande, composer. “Orlando di Lasso – Eco.” Perf. Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Choir. YouTube, 22 March 2010. Web. 18 Feb. 2012. <http://youtu.be/- foB75466zY>.

De Vitry, Philippe, composer. “Medieval music – Vos qui admiramini by Philippe de Vitry.” Perf. Lumina Vocal Ensemble. YouTube, 14 May 2011. Web. 17 Feb. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/4Qatw5B3vc4>.

Dies Irae. 13th C. Benedikt Emmanuel Unger. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 25 June 2006. Web. 7 Aug. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dies_irae.gif>.

Dies Irae. 13th C. Pabix. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 2 Dec. 2007. Web. 26 July 2012. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dies_Irae.svg>.

Gabrieli, Giovanni, composer. “VOCES8: Jubilate Deo.” Perf. VOCES8. YouTube, 14 Nov.

2013. Web. 14 Mar. 2017. <https://youtu.be/RF9MiGJSqd4>.

Gregorian Chant Mass. Internet Archive, 10 March 2001. Web. 26 July 2012.

<http://archive.org/details/GregorianChantMass>.

Hall, Barry, perf. Medieval Fiddle (Vielle) Music. YouTube, 5 Oct. 2008. Web. 15 Feb. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/jPKhBkLgFLk>.

Hildegard von Bingen, composer. Columba Aspexit. Perf. Gothic Voices. Last.fm., 4 July 2012. Web. 28 July 2012.

<http://www.last.fm/music/Hildegard+von+Bingen/_/Columba+Aspexit>.

Hildegard von Bingen. Text and Translation of Plainchant Sequence Columba Aspexit by Hildegard von Bingen. New York University School of Continuing and Professional Studies. N.d., Web. 7 Aug. 2012.

<http://www.kitbraz.com/tchr/hist/med/hildegardtxt.columba.html>.

Iowa State University Musica Antiqua. Pipe and Tabor. Iowa State University. N.d., Web. 19 April 2019. <http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/pipetabr.htm>.

—. The Bladder Pipe. Iowa State University. N.d., Web. 19 April 2019.

<http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/bladpipe.htm>.

—. The Hurdy-Gurdy. Iowa State University. N.d., Web. 19 April 2019.

<http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/hurdy.htm>.

—. The Lizard. Iowa State University. N.d., Web. 19 April 2019.

<http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/lizard.htm>.

—. The Lute. Iowa State University, N.d. Web. 19 April 2019.

<http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/lute.htm>.

—. The Psaltery. Iowa State University. N.d., Web. 29 April 2019.

<http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/psaltery.htm>.

—. The Recorder. Iowa State University. N.d., Web. 19 April 2019.

<http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/r_record.htm>.

—. The Renaissance Shawm. Iowa State University. N.d., Web. 19 April 2019.

<http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/renshawm.htm>.

—. The Serpent. Iowa State University. N.d., Web. 19 April 2019.

<http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/serpent.htm>.

—. The Transverse Flute. Iowa State University. N.d., Web. 19 April 2019.

<http://www.music.iastate.edu/antiqua/tr_flute.htm>.

Memoryboy. Contrary Motion. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 9 June 2008.

Web. 16 Feb. 2012. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ContraryMotion.png>.

—. Oblique. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 9 June 2008. Web. 16 Feb. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oblique.png>.

Merulo, Claudio, composer. “Claudio Merulo (1533-1604) – Toccata quarta del sesto tono (M. Raschietti – Organ).” Perf. M. Raschietti. YouTube, 10 Nov. 2009. Web. 9 Aug. 2012. <http://youtu.be/VUR6kW-Gfh0>.

“mode”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 12 Feb. 2012

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/386980/mode>.

Morn. St. Mark’s Basilica, View from the museum balcony. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 17 May 2011. Web. 28 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St._Mark%27s_Basilica,_View_from_the_ museum_balcony.jpg>.

Neitram. Streichpsalter-Spielerin. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 4 Aug. 2007.

Web. 27 July 2012. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Streichpsalter- spielerin.jpg>.

OboeCrack. Three double reed instruments. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 11 Sept. 2008. Web. 28 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cu_oboe.jpg>.

Da Palestrina, Giovanni Pierluigi, composer. “Gloria – Missa Papae Marcelli – Palestrina.” Perf. Oxford Camerata. YouTube, 13 Jan. 2012. Web. 10 Apr.. 2014.

<http://youtu.be/5k3bfqQ1SpU>.

Pérotin, composer. “Pérotin – Viderunt Omnes, Sheet Music + Audio.” Perf. The Hilliard Ensemble. YouTube, 19 Aug. 2010. Web. 16 Feb. 2012.

<http://youtu.be/aySwfcRaOZM>.

—. Viderunt Omnes. Circa 1200 CE. Manuscript. Bibliotheca Mediceo Laurenziana.

Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation,1 Jan. 2010. Web. 8 Aug. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:P%C3%A9rotin_-_Viderunt_omnes.jpg>.

Phintias . Music Lesson. 510 BCE. Bibi Saint-Pol. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation,10 Sep. 2007. Web. 6 Aug. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Music_lesson_Staatliche_Antikensammlu ngen_2421.jpg>.

Pollini. Trovadores. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 6 Sep. 2008. Web. 26 July 2012. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trovadores.png>.

Praetorius, Michael. Renaissance recorder flutes. 3 Sept. 2005. Wikimedia Commons.

Wikipedia Foundation, 5 March 2012. Web. 7/29/12.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Barocke_Blockfl%C3%B6ten.png>.

Sadler, Joseph Ignatz. Saint Gregory the Great. 18th C. David Hrabálek. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 19 Aug. 2008. Web. 10 Feb. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kostel_Nejsv%C4%9Bt%C4%9Bj%C5%A1

%C3%AD_Trojice_(Fulnek)_%E2%80%93_frs-009.jpg>.

Song of Seikilos. Perf. Atrium Musicae de Madrid. YouTube. 6 Sep. 2008. Web. 15 Feb.

2012. <http://youtu.be/9RjBePQV4xE>.

Sumer Is Icumen In. Blahedo. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 21 Dec. 2005.

Web. 16 Feb. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sumer_is_icumen_in.png>.

“Sumer Is Icumen In.” YouTube, 15 June 2008. Web. 12 Jan. 2017.

<http://youtu.be/PR1jNb7pFNw>.

Verdi, José. Medieval Fiddle or Vielle. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 2 Dec.

2011. Web. 27 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fidulaconfrascos.JPG>.

“Viderunt Omnes (Christmas, Gradual).” Perf. Choir of the Monks of the Benedictine Abbey of St. Martin, Beuron. Youtube, 10 April 2011. Web. 28 July 2012.

<http://youtu.be/EN73kO2_PZA>.

Zuffe. Notre Dame de Paris. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 28 April 2009.

Web. 28 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Notre_Dame_dalla_Senna.jpg>.