3 Chapter 3 The Baroque Era

By David Whitehouse

The term baroque is an arbitrary term used for stylistic practices existing from 1600 to 1750. It may derive from the word barroco in Portuguese meaning “oddly shaped pearl.” Originally used in a derogatory fashion to describe artistic trends of this time period, baroque has come to broadly refer to the century and a half beginning in 1600. This time period, known as

The term baroque is an arbitrary term used for stylistic practices existing from 1600 to 1750. It may derive from the word barroco in Portuguese meaning “oddly shaped pearl.” Originally used in a derogatory fashion to describe artistic trends of this time period, baroque has come to broadly refer to the century and a half beginning in 1600. This time period, known as

the Baroque era, saw the rise of scientific thinking in the work of discoverers such as Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, William Gilbert, Robert Boyle, Robert

Figure 3.1 Baroque art and music exhibited drama, underlying structure, grandiose dimensions, synthesis of religion and secularism, and florid ornamentation. This picture shows a Baroque organ case made of Danish oak in Notre Dame Cathedral, St. Omer, France.

Hooke, and Isaac Newton. Changes in the arts were ushered in by painters such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, Peter Paul Rubens, Andrea Pozzo, and el Greco. Architecture underwent fascinating changes, including boldness of size, curving lines

suggesting motion, and ornate decoration. These trends are represented in the works of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, a leading sculptor and prominent architect in Rome.

Figure 3.2 This view of St. Peter’s Square in Rome shows Bernini’s famous columns, four rows deep and curving, as if they were massive arms enveloping the faithful. Figure 3.3 Francesco Mochi, St. Veronica, 1580. This sculpture by Mochi, who lived from 1580 to1654, shows the drama of movement carved in marble.

Sculptors, too, took a turn toward the dramatic and ornate in their works. The marble statue of St. Veronica by Francesco Mochi shows trends toward vivid motion, dramatic action, and a play to the emotions, including religious fervor.

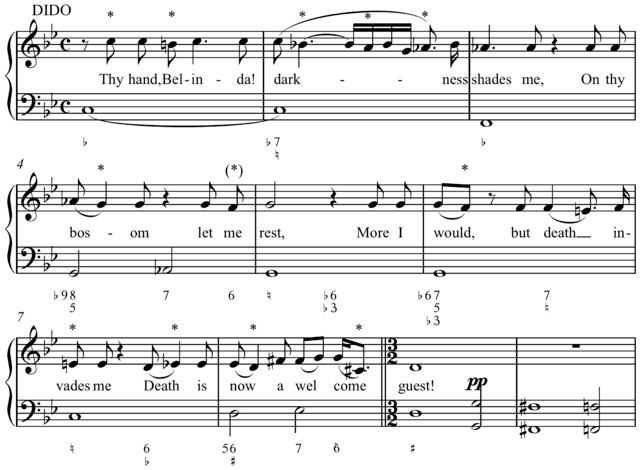

All of Baroque art, including music, has a tendency to be dramatic. Drama in music was displayed most obviously in opera but extended to sacred, secular, vocal, and instrumental music. In music for solo instruments—solo voice, orchestra, and orchestra with chorus—the use of musical devices enhanced musical forms and techniques of the previous era. These devices included increasingly daring use of dissonance (harsh sound), chromaticism (half-step motion) and the use of altered notes, counterpoint that was driven by harmony where horizontal musical lines suggested vertical chords, regularity of rhythm with the universal use of bar lines, and ornamentation of melodic line.

In addition, there was free use of improvisatory skill using the device known as basso continuo, the use of harpsichord and cello playing from musical shorthand. In this practice, the composer wrote down the desired bass notes along with the melody line. Above or below the bass line the composer wrote numbers to indicate what notes were to go along—the so-called figured bass (figure signifies the number above the bass line). The exact way

the performer played these suggestions, however, was left up to his or her skill and taste. Instead

Figure 3.4 Rembrandt van Rijn, The Music Party, 1626, “Jam Session” so to speak?. This work by Dutch painter Rembrandt (1606- 1669) shows dramatic use of light, gesture, facial expression, and color.

of just playing clusters of chords underneath the melodic line, the performer could include passing notes, trills, suspensions, ornaments, flourishes, and other devices to add interest to the music.

Figure 3.1 This excerpt from Henry Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas shows figured bass. Solitary flat and natural signs refer to the third of the chord. Ctrl+click on image to listen to this excerpt.

Figure 3.1 This excerpt from Henry Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas shows figured bass. Solitary flat and natural signs refer to the third of the chord. Ctrl+click on image to listen to this excerpt.

As the seventeenth century progressed, the tendency of all music was toward major and minor tonality, arrangements of notes in scales that are still use today, which was in direct contrast to the use of late-medieval modes through the end of the sixteenth century, especially in church music. (see the example from Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina in Chapter 2). Theorists reflected this tendency in new rule books written to instruct those intending to become composers. Johann Joseph Fux wrote a treatise on counterpoint called Gradus ad Parnassum (Steps to Parnassus) in 1725. Jean-Phillippe Rameau (1683-1764), who was influenced by the writings of René Descartes and Newton, wrote Traité de l’harmonie (Treatise on Harmony) in 1722. Both of these works were used and revered for the next two-

hundred years. Today, Rameau’s ideas, though revolutionary at the time, are learned by every student of harmony as the foundation of the foundation of musical learning.

Baroque Composers:

As musicians and composers traveled all over Europe and heard each other’s music, the new conventions they encountered made subtle impressions on them. Some of the best known composers from the period include the following:

Italy: Monteverdi, Frescobaldi, Corelli, Vivaldi, Domenico and Alessandro Scarlatti

France: Couperin, Lully, Charpentier and Rameau

Germany: Praetorius, Schein, Scheidt, Schutz, Telemann, Handel and Bach

England: Purcell

Opera

The dramatic and expressive capabilities shown in the Renaissance madrigal, especially in Italy, paved the way for the birth of opera, stage works that are entirely sung. Through their interest in how Greek and Roman civilizations presented dramatic works and how music was used to enhance those productions, composers in seventeenth-century Italy sought to incorporate ideas from ancient sources into their own creations. In the works of two notable Italian composers, true opera was born. Jacopo Peri (1561-1633) and Giulio Caccini (1551-1618) are generally credited with giving opera its unique style in two respects: recitative and aria, two techniques to convey dramatic action and feeling in the course of a sung play. Please note that for this chapter, transcripts of song and music lyrics are not necessary to gain an understanding of the material.

Recitative (narrative song) was developed to convey dialogue and aria (meaning “air” or expressive melody) was designed to convey intensity of emotion in the characters using aspects of melody derived from the madrigal. These techniques made opera distinct from earlier plays that used music to a greater or lesser extent. In addition to developing these two types of vocal declamation, Peri and Caccini were convinced that ancient Greek plays were sung throughout, with no spoken dialogue, and sought to emulate this technique in their new genre. Thus, everything was set to music meant to convey the emotions of the characters. The combination of these techniques in one package gave birth to the new form of music called opera.

As with all types of art and new advances in technique, the first practitioners of that art merely hinted at the possibilities inherent in new design and practice. Claudio

Monteverdi (1567-1643) was the first master of opera to uncover and point the way to the rich possibilities inherent in the genre. In his early career, Monteverdi published madrigals in the older style of Renaissance polyphony. In 1605 and thereafter, his published books of madrigals also contained

Monteverdi (1567-1643) was the first master of opera to uncover and point the way to the rich possibilities inherent in the genre. In his early career, Monteverdi published madrigals in the older style of Renaissance polyphony. In 1605 and thereafter, his published books of madrigals also contained

Figure 3.2 Portrait of Claudio Monteverdi, after Bernardo Strozzi.

Monteverdi was the first master of opera to uncover and point the way to the rich possibilities of the genre.

songs in homophonic style, a break from the past. Homophony is music that has a melody with chordal accompaniment. All contemporary popular songs, for instance, are homophonic. Bringing one melody to the fore allowed composers to convey the meaning of words in clearly defined ways. Doing so was not possible, they felt, with older techniques of polyphony, which laid equal emphasis on each

melodic line and often had differing texts for each line of music. Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo was the first opera of significance utilizing the new techniques of aria and recitative. Listen to Arnalta’s aria, “Oblivion Soave,” from Act II of Monteverdi’s final opera, L’incoronazione di

Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea).

As Poppea is overcome by fatigue, her old nurse and confidante, Arnalta, sings her a gentle lullaby. The aria is full of deep emotion, tenderness, and sadness. This display of emotion is evident in the new style of opera and can be considered a general tendency of the Baroque period called the doctrine of affections. This theory showed itself in music by a close association of the meaning of the words with musical devices used. Thus, for example,

words such as running or texts conveying activity would be reflected in quick passages of sixteenth notes, while words of sadness would be reflected in a slow tempo.

This excerpt shows a modern staging of the beginning of L’Orfeo. The opening

instrumental sets a serious tone. Dark emotions are in the foreground. Orpheus makes his entrance and sings to establish place. After the first shepherd sings his response, a group of shepherds make their assertions about the character of their work, followed by a chorus of nymphs and shepherds. The mood of the music is one of jubilation, of seriousness of intent, and of reflecting the meaning of the words in the context of relation to each other.

Monteverdi’s Italian opera continued to develop. The principle centers of growth and experimentation were Venice, Milan, and Florence, but use of operatic elements in other dramatic situations continued in these places and elsewhere in Italian society. Vocal chamber music, on a smaller scale than the opulent productions of opera, nonetheless reflected the developments in dramatic expressiveness, recitative text declamation, and especially in the composition of arias. In the church, composers continued to use the old polyphonic contrapuntal style but increasingly incorporated the use of basso continuo, recitative, and aria.

Instrumental Music

In instrumental music in the second half of the seventeenth century, Italians retained their preeminence as they did in opera. Great violin makers such as Nicoló Amati (1596-1684), Antonio Stradivari (Stradivarius, 1644-1737), and Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri (1698- 1744) made instruments of unrivaled expressive capability and technical reliability.

“The Red Violin” – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RoDpRmfKRvA

Figure 3.3 This image shows a pair of Baroque trumpets. Notice the elongated bodies and lack of valves. Figure 3.4 This image shows a Stradivarius violin circa 1687.

These instruments went hand in hand with the development of the sonata (a work for solo instrument with keyboard accompaniment) and the instrumental concerto (a work for solo instrument with orchestral accompaniment). Composers such as Archangelo Corelli (1653-1713) composed works called sonata da camera (chamber sonata) and sonata da chiesa (church sonata), which were set in a form that came to be known as the trio sonata because they most often were for three players, a harpsichord, and a violin, with a cello reinforcing the bass line of the harpsichord. Set in groups of movements, these sonatas featured contrasting styles between movements, florid melodies, ornamentation, double stops, and flourishes that displayed virtuosity and wealth of invention. The music was increasingly marked by a tonal center emphasizing the major and minor tonalities over the older use of modes.

The instrumental concerto also achieved growing use in Italy and spread to other countries throughout this period. The concerto grosso, written for a larger ensemble known as the Baroque orchestra, contained music for a small group within the larger ensemble,

thus providing for dialogue effects and shifts in dynamics that continued to be exploited throughout the eighteenth century in Italy and other countries. This shift in dynamics was not gradual; it was made in an instant between the larger and smaller ensembles and gave rise to the technique of terraced dynamics (levels of loudness). In addition, the concerto grosso was set in a form that is termed ritornello (return), which meant a return to the full orchestra from flights, called episodes, of the smaller ensemble, often with the same music upon each return. Ritornello form was developed by Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741).

The Baroque suite is a collection of dances of Renaissance origin that developed in the Baroque era to reflect general musical tendencies. These tendencies were regularly recurring rhythmic patterns (meter), gravitation to major and minor tonalities (moving away from the use of Renaissance modes), and firming up of binary (AB) and ternary (ABA) forms (A signifies an opening section of music, B is a departure to a second section of music, and A is a return to the opening).

Early Keyboards

Keyboard music holds a place in the canon of Baroque instrumental music. Keyboard instruments include the clavichord – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2PsYnu2msUU, the harpsichord – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7jWYiQz1cA, and the pipe organ – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BxRriOhKIHE. The harpsichord became the predominant keyboard instrument of orchestras and chamber music, and the organ became the principle accompaniment instrument of church services, with solo works of increasing complexity being written for both throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Two principle genres of keyboard music during this era were the Baroque suite and the fugue (an imitative, polyphonic composition). It is important to remember that composers used these two forms in other music as well, including instrumental music, but these forms predominated in keyboard music.

Bartolomeo Cristofori (Italy) – invented the piano-forte 1700

The piano was clearly indebted to the harpsichord — in early records, Cristofori called the piano an Arpicembalo, which means “harp-harpsichord,” and he frequently worked on and invented other harpsichord-like devices. But the piano took one big step beyond that instrument by using a hammer instead of plucking a string. That allowed for a better modulation of volume thanks to its hammers and dampers, which could more artfully manipulate sound than the plucking motion of the harpsichord.

Though Cristofori was clearly the inventor of the piano, it’s less clear exactly why he’s forgotten outside of musical circles. It may be a combination of his employment, the piano’s slow adoption, and the subsequent improvements. He wasn’t famous when he was alive — and he isn’t particularly famous today. But in a way, that nuance is appropriate for an inventor who introduced new shades of sound to music. Cristofori’s legacy isn’t the sharp plucking of a harpsichord — it’s a piano, playing still.

Pianoforte – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XDJ2O4P97I

The fugue is an extended piece of polyphonic writing for instruments in which a theme is treated in various ways depending on the composer’s skill and ingenuity. Beginning with a subject (theme), a second statement of the subject is made in another voice, with the first voice accompanying it with a new melody called a countersubject. As voices enter, they play the subject while other voices supply accompanying material, including the countersubject. Various keys are explored via modulation (change of key), and other devices are used to show compositional skill and inspiration, including augmentation, diminution, inversion, and stretto (overlapping of subject). The exposition is the first part of the fugue where all voices make their entrance. Episodes occur between statements of the theme, and pedal point occurs when one note is held (usually in the bass) for a long period, building suspense and usually leading to the close.

In all genres of the Baroque era—opera, solo song, sonata, concerto, church cantata, oratorio, suite, and fugue—the music provided the performers with vehicles to show off their abilities. The emphasis on the solo singer in arias of opera and the instrumental soloist in concertos and sonatas paved the way for the development of the virtuoso player/composer and the operatic diva in the Classical era as well as the exploitations of virtuosos in the nineteenth century.

Cantata and Oratorio

The eighteenth century saw the rise of two types of compositions for chorus, soloists, and orchestra. The cantata is a vocal piece in several movements usually based on a single melody. It typically begins with an opening piece for full chorus and orchestra then continues with alternating solos, duets, small ensembles, and other choruses, ending with a statement of the melody. Cantatas are classified as either secular or sacred depending on the text

used. Antonio Vivaldi, George Frideric Handel, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Domenico Scarlatti, Johann Sebastian Bach, and others composed cantatas during the Baroque era.

The oratorio is also a vocal work of music, written in movements with soloists, chorus, and orchestra. The texts used are taken from Biblical scripture or are based on sacred themes. Oratorios incorporate the operatic devices of recitative, aria, and chorus to convey the action contained in the text. Though they are sacred in nature, they are not necessarily performed in church nor are they designed to be included in liturgy like cantatas sometimes are. Italian and German oratorios predominated with Handel in England synthesizing elements of various styles in his unique blend. Perhaps the most famous of all oratorios is Handel’s Messiah. Other oratorio composers include Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Heinrich Schütz, and J. S. Bach.

Listening Goals

- In Baroque opera and oratorio, listen for the fluid sound of an aria. How does it differ from the declamatory (i.e., reciting speech set to music) style of recitative?

- In the Baroque concerto for orchestra, listen for terraced dynamics. When is the full ensemble playing and when is the smaller ensemble playing?

- Terraced dynamics can be heard in solo organ and harpsichord music from the Baroque era. Echo effects were popular. Solo means these instruments were playing alone with no other instrument playing. Listen to solo organ and solo harpsichord music from the Baroque era. The effects that are achieved include echo, terraced dynamics, and textures that vary from thick to thin.

- While listening to Baroque sonatas, take note of how many movements are there.

What are the tempos of the movements? Can you hear when musical material repeats? Can you hear the use of terraced dynamics?

Key Music Terms

Instrumentation Five basic classes of instruments—strings, woodwinds, brass,

percussion, and keyboard—were used during the Baroque era. The viol family of stringed instruments gradually gave way to the violin family. Family in this context means

percussion, and keyboard—were used during the Baroque era. The viol family of stringed instruments gradually gave way to the violin family. Family in this context means

soprano, alto, tenor and bass, which cover the full range of sounds from low to high. Renaissance brass instruments developed into the modern trumpet, trombone, and tuba. Hunting horns with no valves developed into the French horn with valves. Woodwind instruments included flutes, oboes, and bassoons. Percussion instruments included kettle drums and little else. Keyboard instruments included clavichord, harpsichord, and organ. In addition, solo singing and singing in chorus led to the use of the human voice as an instrument during the Baroque era.

soprano, alto, tenor and bass, which cover the full range of sounds from low to high. Renaissance brass instruments developed into the modern trumpet, trombone, and tuba. Hunting horns with no valves developed into the French horn with valves. Woodwind instruments included flutes, oboes, and bassoons. Percussion instruments included kettle drums and little else. Keyboard instruments included clavichord, harpsichord, and organ. In addition, solo singing and singing in chorus led to the use of the human voice as an instrument during the Baroque era.

Timbre or Tone Quality What did instruments and human voices sound like in the years 1600 to 1750? When answering that question, think of how we listen to

music today and how people listened to music then. Also think about instruments as solo, part of small ensemble, and part of a full ensemble. A group of violins, violas, cellos, and double basses playing together sound different than a solo string playing alone. The same is true of each family of instruments. Each section of the Baroque orchestra—strings, woodwinds, brass, percussion, and keyboard—has its own group sound. Combining all groups or combinations of groups produces other effects. A composer thinks about his/her tonal resources when deciding what will convey the musical ideas.

Texture Texture has to do with how many instruments are playing and how many lines of music are playing at the same time. You can have a hundred musicians

Texture Texture has to do with how many instruments are playing and how many lines of music are playing at the same time. You can have a hundred musicians

playing the same melody in unison, and the sound will have a different texture than those same musicians all playing different melodies. Which example do you think would be thicker sounding? Baroque orchestras were not as large as Romantic-era orchestras. The instruments did not have as fully developed overtones, so their sound was less full.

Harmony Harmony grew into distinct patterns during the Baroque era. The Western tonal system was finalized when Johann Sebastian Bach equalized the tuning of

Harmony Harmony grew into distinct patterns during the Baroque era. The Western tonal system was finalized when Johann Sebastian Bach equalized the tuning of

the twelve notes of the chromatic scale. Each interval of a fourth above and a fifth below was tuned exactly the same amount, leaving them all slightly but bearably out of tune. All twelve major and minor modes became usable. Harmonic progression could move freely from a starting point to any other point and back again. Composers and theorists such as Johann Joseph Fux and Jean-Philippe Rameau set down strict rules about which harmonies went with other harmonies and how they moved in and out of each other. Forms were based on accepted patterns of harmonic progression. Claudio Monteverdi’s operatic compositions, George Frideric Handel’s oratorios, and other composers’ choral and orchestral compositions advanced the art of homophony. Johann Sebastian Bach brought to perfection the art of Baroque counterpoint, independent musical lines relating to each other.

Tempo Tempos increased in the Baroque era. The basic pulse of music in the Renaissance era was a modern whole note with swift-moving passages in quarter

Tempo Tempos increased in the Baroque era. The basic pulse of music in the Renaissance era was a modern whole note with swift-moving passages in quarter

and eighth notes for human voices. The tempo was even faster for instrumental voices. By the Baroque era, the basic pulse became the modern quarter note with sixteenth notes common for both human and instrumental voices.

Dynamics Dynamics in the Baroque era were classified into levels called terraced dynamics. The sound of a full ensemble was contrasted with a smaller ensemble.

Dynamics Dynamics in the Baroque era were classified into levels called terraced dynamics. The sound of a full ensemble was contrasted with a smaller ensemble.

Harpsichords and organs that had more than one keyboard could instantly jump from one of those keyboards to the other. Both techniques produced terraced dynamics, loud on down to soft. It wasn’t just haut(loud), and bas(soft) anymore. As a general rule, there were no gradual crescendos or diminuendos, as, for instance, in opera and oratorio a human singing solo or a chorus singing together could gradually increase or decrease the sound gradually. The human voice, however, was treated in the same way as instrumental voices. Gradual changes in sound level were not the norm.

Form While musical forms have been in constant development throughout history, several formal designs were finalized in the Baroque era. These forms include the

Form While musical forms have been in constant development throughout history, several formal designs were finalized in the Baroque era. These forms include the

concerto, ritornello, sonata, fugue, toccata, prelude, chorale, theme and variations, opera, oratorio, aria, and recitative. The designation finalized means only for a time, as the enduring aspects of some of the forms underwent further development in ensuing eras.

Some forms, such as the fugue and ritornello, were exploited to their fullest potential by the end of the Baroque era. Others, such as the concerto and sonata, were developed further after the Baroque era.

The Eighteenth Century

The eighteenth century saw the culmination of Baroque practices and the beginning of the Classical period. Musicians cultivated new genres such as opera buffa, ballad opera, keyboard concerto, symphony, and concerto. Composers birthed new forms, like the rondo, and developed others, like the sonata, and thought in terms of tonality (key centers) in all compositions, replacing church modes almost entirely. Endless arguments regarding

musical taste took place in newly invented newspapers, in composers’ journals, in musical treatises, in coffee houses, and in the homes of the populace.

It is important to mention at this point that the tonal system used in the Middle Ages and Renaissance is different from the one used today. The tonal system used during the Middle Ages is called just intonation, which is based on natural harmonics, or the way sound resonates in nature. The major/minor system used today is called equal temperament, which began to be utilized in the Baroque era. Equal temperament is a system of tonality in which all of the notes are distanced equally apart. Technically it is slightly out of tune in relation to how sound resonates in nature. Some cultures, such as the Chinese, have resisted the change to equal temperament, believing that it creates disharmony in the environment. See Chapter 8 to learn more about music in other cultures.

Vivaldi, Handel, and Bach

Antonio Vivaldi, George Frideric Handel, and Johann Sebastian Bach are three composers who represent culminations of styles and practices in full bloom in the mid- 1700s, when instrumental forms such as the concerto, opera, oratorio, cantata, dance suites, and fugue were developed to their highest potential using homophonic, polyphonic, and contrapuntal techniques.

Antonio Vivaldi and the Concerto

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) was born in Venice, Italy, spending a great deal of his life there. He was ordained as a priest in the Catholic Church and spent the greater part of his career as a teacher, composer, conductor, and superintendent of musical instruments at the Pio Ospedale della Pietà. There were four such so-called hospitals in Venice where poor,

Figure 3.5 Pier Leone Ghezzi, The Red Priest, 1723. Ghezzi created this caricature of Antonio Vivaldi using pen and ink on paper.

illegitimate, and orphaned boys and girls were given housing and schooling. All of the students at the Pietà, however, were girls who provided the talent for performing groups, including duos, trios, quartets, and full orchestras. While employed at the Pietà, Vivaldi composed numerous works, including operas, cantatas, sacred music, and concertos, for which he is known today. Vivaldi composed more than four hundred concertos during his lifetime.

The following example is the first movement of the first of Vivaldi’s four concertos called The Four Seasons. Each concerto has three movements and each

is dedicated to one of the four seasons of the year. The first movement, “Spring,” is an example of ritornello form, which is a flexible approach to concerto writing. A small group of players is contrasted with the larger ensemble, with musical motives returning in varied guises as the two groups alternate. Sometimes the material returns with exact repetition, sometimes it’s abbreviated, and sometimes it varies with slight alterations of melodic curve and harmonization. The music is entirely for strings, with a smaller ensemble integrated throughout that admirably demonstrates terraced dynamics. The ensemble is led by a violinist who is joined by other players from the large ensemble to create special effects when contrasting with the entire ensemble. A harpsichord provides the continuo, violins are divided into first and second, and there are violas, and cellos to complete the ensemble. In Vivaldi’s time there were bass viols in this ensemble as well. This collection of instruments

became the standard ensemble of concertos throughout Vivaldi’s writings, but he also wrote solo concertos for various wind instruments and used them in his ensemble writing.

Vivaldi was held in high esteem all over Europe. His trios, solo sonatas, and cantatas reflected earlier masters, showing the propensity for Baroque composers to synthesize and develop existing forms. His concertos developed mainstream tendencies, including three movements (fast, slow, fast), terraced dynamics, and ritornello form. His concerto writing and the broad fame of his concertos helped solidify the concerto form. Vivaldi brought rhythmic vitality and thematic invention to his operas while continuing with advances made by earlier Italian composers. He carried operatic style over to his sacred music. But it is in his varied and prodigious output of concertos in ritornello form that he had the greatest influence.

Johann Sebastian Bach

One of those Vivaldi most influenced was Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach’s musical output represents the culmination of many contrapuntal forms in use during the Baroque era. In his instrumental—including solo keyboard—works, writing for chorus and orchestra, cantatas, passions (church works depicting the life of Christ), and settings of chorales he infused a wealth of technical, melodic, and harmonic richness and variety with a depth of formal organization. His works for solo instruments, especially his keyboard pieces for harpsichord and organ, brought forms such as the toccata (virtuoso keyboard piece), prelude (keyboard piece preceding another), chorale variation (Lutheran church hymn with altering), Baroque sonata, and fugue to perfection. He wrote monumental works for chorus, soloists, and orchestra in the form of two passions, the St. Matthew Passion and the St.

John Passion, and a large-scale setting of the mass, the Mass in B minor, for the same

Figure 3.6 Elias Gottlob Haussmann, Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach, 1748.

instrumental groupings as the passions. Bach worked his entire career for towns and churches, and his positions did not require him to compose any operas. He was a pious Lutheran, heading all of his compositions with the mark S.D.G. (Soli deo gloria) meaning “To God alone be glory.”

Bach spent his entire career in Germany. He traveled when he could, getting into trouble several times with his employers for being away from his

employment too long. On one occasion he walked two hundred miles from Arnstadt to Lübeck to hear the famous organist and composer Dietrich Buxtehude. He arranged several of Vivaldi’s concertos while adding to and strengthening the counterpoint, filling out the melodic contours, and reinforcing the basic harmonic schemes. He was familiar with trends in French Baroque music, including the flair for the dramatic, exquisite use of dissonance and suspension, and vagaries of counterpoint as practiced there. As he sought to educate himself in all styles and to keep abreast of current developments, Bach was a master synthesizer of styles. Bach never imitated other composers; he synthesized stylistic trends and harmonic advances and brought forms to levels of expression unheard of and unmatched since.

The following are three examples of Bach’s enormous output. In “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme” BWV 140 (BWV stands for Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis, the numbering system used to identify Bach’s works), several arrangements of this chorale are heard. The chorale is set in sparse style, with only three lines of music playing: the chorale melody in the tenor voices, and the bass and soprano lines taken by instruments. One can hear the opening melodic motive in the instruments throughout the piece as the chorale soars in long notes on harmonic patterns underpinned by the bass line. This piece is one section of a longer composition, the cantata, mentioned previously. In all of his cantatas, including “Wachet auf,” Bach used conventions of the time, including choral sections both a capella and with accompaniment, arias, orchestral introductions and interludes, and a final setting of the chorale for chorus or chorus with orchestra as the closing of the cantata.

The second example of Bach’s work is from his orchestral music. He wrote six concerti grossi (plural of concerto grosso) for the margrave (ruler) of Brandenburg, a small state near Berlin. Listen to the first movement of the Brandenburg Concerto no. 4 in G major, BWV 1049. Follow along with the PDF music score at Stanford University’s Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities. The piece is scored for a string orchestra consisting of violins I and II, violas, violoncello, violone (contrabass), and continuo. This ensemble is called the ripieno, or full orchestra. In addition, Bach used a violin and two flutes as a smaller ensemble (called solo but actually with three players) to contrast with the ripieno. In thinking of the orchestra in this way, Bach and others in the Baroque era devised ways of contrasting the timbres and dynamics of the music they were writing.

Two principles are evident from hearing the second example above. The first principle is terraced dynamics, clearly heard when the solo (violin and two flutes), and the full

orchestra play. There is an immediate decrease in sound when the smaller group plays and a return to a full sound when the full orchestra plays. No crescendos or diminuendos are heard, thus the designation terraced dynamics. The second principle is ritornello form, which was favored by Baroque composers of concertos. In the case of concertos, ritornello is a return to the music of the opening, much as in popular music of today when a refrain is sung between verses. Each solo section has contrasting music with a division of the sections following a typical pattern: tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti, solo (tutti means “full,” i.e., the ripieno). While that alternating between ripieno and tutti was a typical pattern, composers found flexibility in ritornello form and would often use material from each solo part to enrich the tutti or in combination with other solo sections. The entire piece would be written with Baroque counterpoint, major and minor tonal centers, and rhythmic regularity. These characteristics form the basis of Baroque-era developments of Renaissance ideas or techniques.

orchestra play. There is an immediate decrease in sound when the smaller group plays and a return to a full sound when the full orchestra plays. No crescendos or diminuendos are heard, thus the designation terraced dynamics. The second principle is ritornello form, which was favored by Baroque composers of concertos. In the case of concertos, ritornello is a return to the music of the opening, much as in popular music of today when a refrain is sung between verses. Each solo section has contrasting music with a division of the sections following a typical pattern: tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti, solo (tutti means “full,” i.e., the ripieno). While that alternating between ripieno and tutti was a typical pattern, composers found flexibility in ritornello form and would often use material from each solo part to enrich the tutti or in combination with other solo sections. The entire piece would be written with Baroque counterpoint, major and minor tonal centers, and rhythmic regularity. These characteristics form the basis of Baroque-era developments of Renaissance ideas or techniques.

Figure 3.7 This image shows the opening of the toccata from Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor for organ solo. Notice the ornamentation (squiggly lines above some of the eighth notes), the fast-running passages, and the thick chordal texture of the final notes in the example.

The third example from Bach is his Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565. A toccata (touch) is a keyboard work that shows the dexterity of the player. Composers wrote toccatas from the second half of the sixteenth century through the end of the Baroque era. Using fast- running passages, intricate ornamentation, chromatic harmonies, and thick textures, toccatas were meant to show the resources of the instrument they were written for and the

abilities of the keyboard player. These things are thoroughly explored in Bach’s toccata from the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, which is written and played on the pipe organ. A clear subject, countersubject, and stretto are evident in Bach’s fugue, which has one of the most

abilities of the keyboard player. These things are thoroughly explored in Bach’s toccata from the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, which is written and played on the pipe organ. A clear subject, countersubject, and stretto are evident in Bach’s fugue, which has one of the most

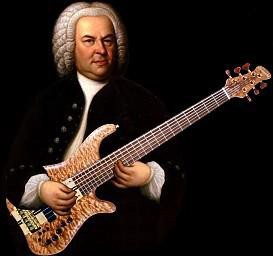

Figure 3.8 Shown is Bach’s portrait by Haussmann brought up to date with a six-string bass. Listen to a power metal version of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor.

recognizable themes of fugal writing in the entire repertoire of classical music. The piece ends with a dazzling display of virtuosity that recalls the toccata and leaves the subject behind.

George Frideric Handel

George Frideric Handel (sometimes spelled Georg Friedrich Händel, among other ways) (1685-1759) was born the same year as Domenico Scarlatti and Bach. He was born in the town of Halle in Saxony. His mother nurtured his musical gifts, but his father hoped that he would study law. The attraction of music was greater than law for Handel and he traveled to Hamburg when he was eighteen, playing in the orchestra there and teaching violin. In 1706,

Figure 3.9 Thomas Hudson, Georg Friedrich Händel, 1748- 49.

Handel traveled to cities in Italy, including Florence, Rome, Naples, and Venice. He studied the Italian styles in vogue at the time, including concertos and opera. He made acquaintances of some of the leading figures in music, including Antonio Lotti, Domenico Scarlatti, and Alessandro Scarlatti. Handel studied with the most renowned Italian composer of the period, Archangelo Corelli, whose compositions for string orchestra solidified the Baroque

concerto grosso form. During his youthful three-year stay in Italy, Handel absorbed Italian vocal and instrumental compositional styles, including a flair for the dramatic.

In 1709, Handel became the Kapellmeister (master of music) for the elector of Hanover but soon after moved to England. There he stayed for the rest of his life, with only brief returns to his native Germany, even though he had obligations as the elector’s music director. This fact proved embarrassing to Handel, as the elector became King George I of Great Britain in 1714. Handel was reunited with his patron when he composed the Water Music suites after a mediator begged them to reconcile. The work was played on a barge on

the river Thames for an evening festival thrown by the king, who had it repeated twice because he loved it so much.

Though Handel was a composer of Italian opera in London during this time, he also forayed into the realm of oratorio. Composing more than forty operas in the Italian style, he eventually stopped composing opera altogether as tastes changed. He then turned exclusively to oratorio. His last opera, Deidamia, was produced in 1741, but Handel had been composing in English as well as Italian since 1733. As he wrote opera he increasingly wrote choruses for oratorios, improving his technique with more chorus work in each succeeding oratorio; double choruses, which are his signature; and balance of chorus movements with solo arias and orchestral preludes and interludes. This experience in writing oratorios led Handel in 1742 to compose his famous Messiah, which premiered on April 13, 1742, in Dublin, Ireland. For the next ten years, Handel composed one oratorio per year on average. His sight began to fail as early as 1750, with complete loss by 1752.

Handel spent his final years supervising performances of his works, writing new material for some of them, and rewriting parts of others. He is buried in Westminster Abbey in London.

The following are two examples of Handel’s prodigious output, which fills one hundred volumes and is almost equal to that of both Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven, both prolific composers, put together. The first example is Suite No. 2, HWV 349, from the famous Water Music suites. The example is called “Alla Hornpipe” and is the second movement of the suite. In it the ABA form can be heard. The A section is a lively dance, with solos for two trumpets and two horns alternating with each other and with the full strings and ending with all instruments playing a cadence. The B section is in a related minor key,

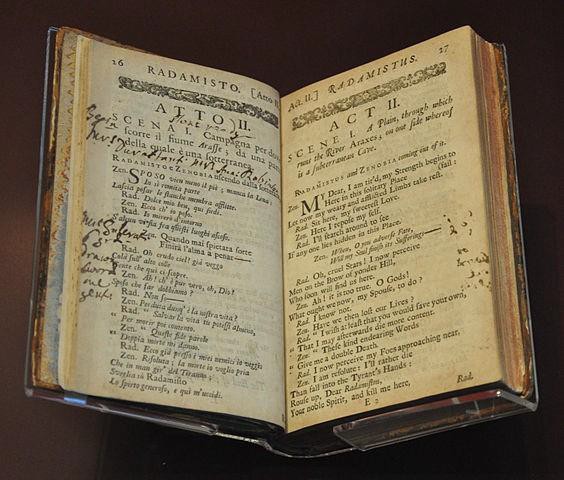

Figure 3.14 Shown is the libretto (with Italian on the left and English on the right) from a prompt book from Handel’s opera Radamisto. Throughout this book, notes were made by the stage hands responsible for things such as lighting, sound effects, and curtain draws. Copies also were available (without notes) for the audiences to read as the opera progressed. Lighting was kept on in the theaters during performances around this time in England. Take an interactive look at this prompt book.

with only the strings playing throughout. The A section returns note for note with no cadenza (ending music incorporated after the main section is played).

The second selection from Handel is from Messiah, an oratorio that is known worldwide. The “Hallelujah” chorus is the culmination of the second section of the three- section work. It is scored for Baroque orchestra and four-part chorus: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. The words are taken from the Bible. Handel composed the music for Messiah in a

heat of inspiration which was much faster than his normal phenomenally quick rate of composing. It took him less than four weeks to complete the entire score in August and September of 1741. In Handel’s oratorios, operatic show of solo voices generally predominate, with the chorus adding portions here and there. In Messiah, however, the chorus work gives impetus to the dramatic response of human beings to the message of divine intervention in the affairs of humans and has much more of an even status with the arias of the soloists. Of all the choruses in the work, the “Hallelujah” chorus remains a favorite, with amateur choirs all over the world attempting to render the piece at Christmas and Easter. And there is no reason to wonder why, as the wedding of text and music has never been more consummate in any other choral work ever written. The words are a jubilant expression of joy to the savior. The music is exuberant, reflecting the intense emotions of an awakening realization of the importance of what the divine has done.

Rhythmic punctuations are enhanced with running passages of strings, marching bass lines, and trumpet calls that ring clearly over all, summoning the faithful to a more intense awareness. The ending climaxes on a rhythmic elongation of the word hallelujah, which is repeated throughout.

What was it like to attend a concert in the baroque era?

In modern times, going to a concert is an event. We hear an ad on the radio or see a listing in the newspaper; we purchase tickets; we go to a concert hall and sit quietly until it is time to applaud. In the baroque era, this kind of public concert was rare. Many of the most famous baroque compositions were performed in churches for a service, or as part of a private concert or celebration in the home of a wealthy patron. During the course of the baroque, however, public performances became more common, particularly in the genres of opera and oratorio, and our modern concert tradition began to coalesce in many European cities.

In an early recollection, a simple concert went something like this: One opened an obscure room in a public house, filled it with tables and seats, and made a side box with curtains for the music. Sometimes ensembles, sometimes solos, of the violin, flageolet, bass viol, lute and song, and such varieties diverted the company, who paid at coming in. One shilling a piece, call for what you please(requests), pay the reckoning(good or bad), and Welcome gentlemen.

The advent of the public concert made the growing middle class an important source of income for musicians. By the end of the baroque, this social subset had become a musical patron almost as powerful as the church or court.

Closing

In Europe around 1600, developments taking place in society were reflected in music. Specific trends included dramatic declamation, formal organization, and the use of standard metrical patterns grouped into measures. These trends also included increasing dissonance, chromatic notes, counterpoint based on harmonic schemes, rhythms that were regulated by bar lines, and melodic lines that were increasingly ornamented. Composer- performer combinations increasingly gave way to performers coming into their own as

separate entities. The Baroque orchestra developed a standard size.( See jpg pic in reference links)

Music publishing developed so that dissemination of styles improved. The design, manufacture, and affordability of instruments improved, and increasingly reliable instruments led to the development of more complex music where forms were explored with new compositional devices. Opera, ritornello, concerto, sonata, fugue, and other forms continued to be exploited by composers, resulting in near exhaustion of their possibilities. By 1750, this exhaustion was leading to a new era of musical history: the Classical period.

Music and Memory

This week, watch the video “Music and Memory,” part of the Annenberg Learner video series we will be viewing throughout the text.

Guiding Questions

- What years are designated as the Baroque era?

- Who were major composers of the Baroque era?

- What forms were used in the Baroque era? List at least five.

- What instruments were used? List instrument families.

- What development allowed all twelve major and minor keys to be used? Who finalized this development?

Self-Check Exercises

Complete the following self-check exercises to verify your mastery of key music terms presented in this chapter. After you have read the questions above, check your answers at the bottom of this page.

- Developments in music during the Baroque era include what?

- Opera, the suite, and fugue

- Ornamentation of the melodic line, regularity of rhythm

- Increasing use of dissonance, use of chromaticism, and regular use of bar lines

- All of the above

- Opera was birthed with two major characteristics. What are they?

- Aria and chorale

- Aria and recitative

- Recitative and brevita

- Drama and declamare

- The tonal system in the Middle Ages and Renaissance went from being based on modes and using just intonation to what system?

- The Romantic-era system of chromaticism

- The Classical-era system of easy conformality

- The Baroque-era system of equal temperament, or major/minor tonality

- The modern system of atonality

- Which set of composers are ALL from the Baroque era?

- Vivaldi, Handel, Bach

- Vivaldi, Handel, Schumann

- Handel, Bach, Gaga

- Vivaldi, Handel, Mozart

Self-check exercise answers: 1. D, 2. B, 3. C, 4. A.

Works Consulted

Bach, Johann Sebastian. Brandenburg Concerto no. 4 in G major. Circa 1721. Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities, Stanford University, 2004. Web. 29 July 2012. <http://scores.ccarh.org/bach/brandenburg/bwv1049/bwv1049.pdf>.

—. Brandenburg Concerto no. 4 in G major. Circa 1721. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 15 Apr. 2011. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brandenburg_No4-1_BWV1049.ogg>.

—. Toccata and Fugue in D minor. Circa 1708-10. Perf. Ian Tracey. June 1989. Music Online: Classical Music Library. Alexander Street Press. Web. 21 Oct. 2014.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/9 28413>.

—. Toccata and Fugue in D minor. Circa 1708-10. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 27 Feb. 2012. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BachToccataAndFugueInDMinorOpening.G IF>.

—. “Bach – Cantata 140: Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140 (1731).” 1731. Cond. Nikolaus Harnoncourt. Perf. Concentus Musicus Wien. Youtube. 23 Jan. 2011. Web. 29 15 Apr. 2014. <http://youtu.be/3sj-NKqR0tw>.

Buxtehude, Dietrich. Jubilate Domino: No. 2 aria. Perf. Columbia Baroque Soloists. Early Music America. 21 Dec. 2011. Web. 24 Feb. 2012.

<http://www.earlymusic.org/audio/jubilate-domino-no-2-aria>.

Construction tools sign, used with permission from Microsoft. “Images.” Office. Web. 4 Sept.

2012. <http://office.microsoft.com/en- us/images/results.aspx?ex=2&qu=tools#ai:MC900432556|mt:0|>.

Ghezzi, Pier Leone. The Red Priest. 1723. Codex Ottoboni, Vatican Library, Rome. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 13 Aug. 2012. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vivaldi_caricature.png>.

Grossman, Dave. Updated Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach. 10 July 1999. Johann Sebastian Bach. (unpronounceable) Productions, 18 Sep. 2007. Web. 29 July, 2012.

<http://www.jsbach.net/bass/>.

Haas, Johann Wilhelm. Baroque trumpets. Photo by BenP. 12 Jan. 2006. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 16 Apr. 2012. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trompettes_baroques.jpg>.

Handel, George Frideric. “Alla Hornpipe.” Water Music. 1717. Cond. Rimma Sushanskaya. Perf. Berlin Sinfonietta. Berlin Philharmonic Hall, Berlin. 25 Dec. 2008. YouTube. 11 March 2009. Web. 29 July 2012. <http://youtu.be/TRNmXwNnB9w>.

—. “Hallelujah.” Messiah. 1741. Cond. Stephen Simon. Perf. Handel Festival Orchestra of Washington, D.C., and Howard University Choir. 1985. Music Online: Classical Music

Library. Alexander Street Press. Web. 21 Oct. 2014.

<http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?url=http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/1 78837>.

Haussmann, Elias Gottlob. Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach. 1748. Collection of Dr.

William H. Scheide, Princeton, New Jersey. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 10 Dec. 2011. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Johann_Sebastian_Bach.jpg>.

Hudson, Thomas. Georg Friedrich Händel. 1748-49. Hamburg State and University Library, Hamburg, Germany. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 11 March 2012. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Georg_Friedrich_H%C3%A4ndel.jpg>.

Lully, Jean-Baptiste. “Enfin il est en ma puissance.” Armide. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 5 Mar. 2012. Web. 13 Mar. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Armide_Enfin.ogg>.

Mochi, Francesco. St. Veronica. 1629. St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome. Wikimedia Commons.

Wikipedia Foundation, 18 April 2012. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Francesco_Mochi_Santa_Ver%C3%B3nica

_1629-32_Vaticano.jpg>.

Monteverdi, Claudio. “L’Orfeo.” 1607. YouTube. 10 Jan. 2009. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://youtu.be/jb2TURdBeEQ>.

—. “Oblivion Soave.” L’incoronazione di Poppea. 1642. Perf. Karim Sulayman. Guy Barzilay Artists. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://guybarzilayartists.com/upload/audio_Sulayman2.mp3>.

“Music and Memory.” Exploring the World of Music. Prod. Pacific Street Films and the Educational Film Center, 1999. Annenberg Learner. Web. 31 July 2012.

<http://www.learner.org/vod/vod_window.html?pid=1239>.

Plamondon, Taran. “Bach Rock.” YouTube. 23 Dec. 2010. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://youtu.be/I6pwtZsYuG4>.

Portrait of Monteverdi, after Bernardo Strozzi. N.d. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 13 June 2012. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Claudio_Monteverdi.jpg>.

Praefcke, Andreas. Prompt book for Radamisto 1720 VA. June 2011. Wikimedia Commons.

Wikipedia Foundation, 1 July 2011. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prompt_book_for_Radamisto_1720_VA.jp g>.

“Prompt book for Radamisto by George Friedrich Handel.” 1720. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/p/prompt-book-for-radamisto-by-george- friedrich-handel/>.

Purcell, Henry. “Purcell diatonic chromaticism.” 14 Jan. 2011. Wikimedia Commons.

Wikipedia Foundation, 12 Mar. 2012. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Purcell_diatonic_chromaticism.png>.

—. “Henry Purcell – Dido and Aeneas – Dido’s lament 1688. Perf. Xenia Meijer. YouTube. 11 June 2010. Web. 60 Apr. 2014. <http://youtu.be/ivlUMWUJ-1w>.

Stradivari, Antonio. Spanish II violin. 1689. Palacio Real de Madrid, Spain. Photo by Hakan Svensson. 23 July 2003. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 21 April 2010.

Web. 28 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PalacioReal_Stradivarius1.jpg>.

Reinholdbehringer. Baroque Organ, Cathedral of St. Omer. 30 Dec. 2011. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 11 Jan. 2012. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baroque_Organ,_Cathedral_of_St.Omer.JP G>.

Valyag. Saint Peter’s Square from the Dome. 26 May 2005. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 5 July 2010. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saint_Peter%27s_Square_from_the_dome

_v2.jpg>.

van Rijn, Rembrandt. The Music Party. 1626. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 16 May 2012. Web. 26 Feb. 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rembrandt_concert.jpg>.

Vivaldi, Antonio. “La Primavera (Spring).” The Four Seasons. 1723. Perf. John Harrison and Wichita State University Chamber Players. Cond. Robert Turizziani. Wiedemann Recital Hall, Wichita State University. 6 Feb. 2000. Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia Foundation, 13 April 2012. Web. 29 July 2012.

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:01_-_Vivaldi_Spring_mvt_1_Allegro_-

_John_Harrison_violin.ogg>.